What might the American economy look like if policy-makers had not engaged in decades of brutal betrayal against American workers?

A new report from the Congressional Budget Office provides an eye-opening answer to the question by examining a sector of the labor market whose wages have been largely shielded from the effects of trade deals, immigration, and job-killing regulation. These workers receive wages and benefits that are, on average, about 17 percent higher than workers with comparable skills and education in other parts of the economy.

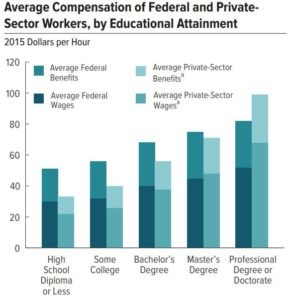

The compensation gap is striking. The workers in the protected sector are better compensated than unprotected peers at every level of educational attainment aside from those with professional degrees or doctorates. The compensation gap is largest, in fact, for those workers who would otherwise be among the most vulnerable in the economy: workers with no more than a high school degree. According to the CBO study, the total compensation for protected workers with a high school diploma or less earned 53 percent more than their unprotected peers.

So who are these protected workers? They are members of the federal government’s civilian workforce.

The federal government employs about 1.5 percent of the U.S. workforce, around 2.2 million workers. They are spread across more than 100 agencies and over 650 occupations. In fiscal year 2016, the federal government spent around $215 billion to compensate these workers. On average, they tend to be older, more educated, and more concentrated in professional occupations than private-sector workers.

The CBO studied data from 2011 through 2015 to estimate the differences between the wages and benefits of federal employees and similar private-sector employees. It sorted the data by level of education, years of work experience, occupation, size of employer, geographic location, veteran status, and demographic characteristics such as ages, sex, race, and marital status.

What it found was that federal workers tend to earn far more than their private sector counterparts. Between 2010 and 2015, federal workers with a high school degree or less had wages that were 34 percent higher than private sector peers and benefits that were 93 percent greater, for a total compensation gap of 53 percent. For workers with a bachelor’s degree, the wage gap was 21 percent, composed of a 5 percent wage gap and a 52 percent benefit gap.

Aside from those with the highest levels of education, the compensation gap has grown in recent years. Between 2005 and 2010, for example, the total compensation gap for workers with a high school diploma or less was 36 percent. The gap for those with a bachelor’s degree was 15 percent.

An adjustment to whom is counted as a federal employee caused some of this difference. But the larger part of it was caused by the fact that wages grew more quickly among less educated federal workers than those in the private sector. This is even more striking because lawmakers froze across-the-board salary increases for federal workers between 2011 through 2013. Without this freeze, the gap would have grown even larger.

Federal workers are shielded from a lot of the effects of globalization that have depressed private sector worker compensation. Their jobs are not easily or often subject to off-shoring, the practice of replacing employees in the U.S. with employees located in foreign countries. Similarly, outsourcing does not weigh on federal workers the way it does private sector workers. Competition from immigrants is far less of a factor because the U.S. government has stringent rules against hiring illegal immigrants and does not directly seek workers from abroad to fill jobs. While the federal government hires immigrant workers, it does so from the pool that is already legally residing in the United States.

Trade hardly impacts federal worker compensation at all. Civilian federal employees working in the Defense Department, the largest group of federal workers, are not in wage competition with defense workers in foreign lands. That is true for almost all federal workers, in fact. From the Department of Agriculture and the Department of the Interior to the U.S. Treasury and the Justice Department, the wage competition faced by employees is purely domestic.

Unlike the private sector, where employment and wages are depressed because of regulation, the federal government benefits from increased regulation. Each new regulation requires employees to enforce and monitor compliance. And most regulations impose few barriers to projects that the federal government pursues.

Look at it from the point-of-view of the agencies. They are confined to hiring, for the most part, American citizens and legal residents. They compete with other government agencies and the private sector for workers. While the private sector can turn abroad for workers, the federal agencies cannot. The result is higher wages and better benefits for federal workers.

Importantly, many of the non-policy sources of wage stagnation that impact the private sector also weigh on the federal sector. Communications technology, for example, has made many occupations once filled by workers in the federal government redundant. Robotics, improved computer processing, and the Great Recession–recall that wage 2011-2013 wage freeze–have all hit federal workers. Yet the compensation grew. That leaves the effects of trade and immigration policy as the most likely culprits.

The absence of a wage gap for those with a doctorate or professional degree is telling. In the private sector, these are workers who have faired relatively well in the age of globalization. Many have seen the demand for their work–and therefore their prosperity–rise as lawyers, bankers, and other professions ply their trade internationally. So it is no surprise that the federal workers with advanced degrees earn 18 percent less than private sector counterparts.

This fact also undermines a competing narrative explaining the wage gap–that it is a result of a reckless federal government that spends willy-nilly and cannot resist pressure for higher wages. If that were so, all federal workers would be expected to earn more.

The compensation gap could also explain why so many federal workers do not look favorably on President Donald Trump. They just have not experienced the economic impact of globalization the way many of Donald Trump’s private sector supporters have.

The CBO report is a glimpse into a shadow world, an alternate reality of an American economy absent the trade and immigration policy decisions that have dragged down all but the best educated and highest earning segments of the American workforce. It shows us an America where a worker without a high school diploma is far better paid and the rewards to the elites are far less grand. It is the world without the carnage that globalization has sown in the American economy.

It is, more hopefully, a roadmap to making America great again.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.