Welcome to the Full-Employment Economy

Can the jobs numbers really be as good as they look?

The Department of Labor will release the April employment report on Friday. It is expected to show that employers added 250,000 workers to their payrolls, and the unemployment rate is expected to hold steady at 3.8 percent.

If the estimates are right, this will be the 27th month in which the unemployment rate has been below four percent. That’s the longest stretch since the late 1960s, when the draft for the Vietnam war was diverting a significant share of workers into the military.

That may actually understate how long a stretch we have been in a full-employment economy. The unemployment rate dropped below four percent in March of 2018, something it had only done in a single month in 2020 and before that not since 1969. If we look through the pandemic, scratching out employment from March 2020 through the next two years, we’ve actually been in a period of extremely low unemployment for 73 months or around six years.

That is longer than the late 1960s stretch of low unemployment. It’s longer than the Eisenhower period of low unemployment. In fact, it’s the longest stretch of below ultra-low unemployment since the government started keeping reliable records following World War II.

Neither our politics nor our economic analysis has really kept up with this development. Politicians and bureaucrats still talk about their programs in terms of jobs created or jobs destroyed. When the Biden administration slapped a ban on noncompete agreements on the U.S. labor market, for example, it made sure to claim that this would create jobs. Same with the administration’s various green energy proposals. Even its tax proposals come wrapped in language saying they will prevent companies from “shifting jobs and profits overseas.” No matter what the policy details or larger goals, they’re always presented by their advocates as creating or defending jobs.

And when critics of Biden’s policies speak, they often talk about job destruction from too much taxation or regulation. When the Tax Foundation looked at the Biden administration’s 2025 budget proposal, it said that it would kill about 788,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

This focus on job creation or destruction makes sense in an economy that has a lot of what economists call “slack” in the labor market. When unemployment is high, there is a lot of unused labor capacity that is basically wasted by not being employed. Programs that promise to decrease unemployment aim to better utilize the great natural resource of U.S. labor.

In an economy operating at full employment for more than half a decade, this becomes maladaptive. Programs that require lots of workers are not creating jobs but requiring either the diversion of workers from other parts of the economy or the opening of the economy to more immigrants. Re-allocating workers according to a changing economy is healthy, but doing so because the government is artificially creating labor demand in some parts of the economy is usually a recipe for economic waste.

What’s needed in a full-employment economy is not subsidies for job creation but the removal of barriers that prevent workers from moving into occupations where they are most needed. The natural flow in a full-employment economy is from lower productivity jobs to higher productivity jobs. The increased productivity helps combat the inflationary pressure of full-employment. Instead of government programs promising a helping hand, the economy is calling out for programs that get the government out of the way of people getting better jobs.

Aren’t They All Just Part-Time Jobs and People Holding Down Three Jobs to Make Ends Meet?

It’s only natural that there is some skepticism about this new economic reality. We suffered through years of inadequate demand for labor following the financial crisis, and both our political and economic analysts became accustomed to treating this as a permanent state. The assumption became that the economy had reached what economists call a “low employment equilibrium.”

In fact, the problem of inadequate demand goes back even further, arguably to the 1970s. In most of the 50 years that preceded the pandemic, the economy experienced a huge increase in workers through both the entry of women into the workforce and heightened levels of immigration. Most of those new workers were absorbed into the economy but at the cost of decades of elevated unemployment.

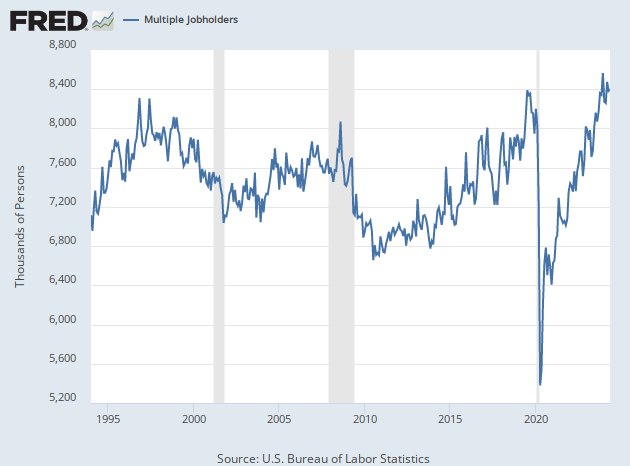

One source of skepticism about the employment statistics that we frequently hear is that a lot of people are holding multiple jobs. Since Biden took office, the critics point out, the number of people holding multiple jobs—which includes both full-time and part-time workers—has grown by 1.8 million. And since the official payroll numbers that get released each month can double-count workers who are on two different payrolls, this is seen as overstating the strength of the labor market.

The chart below shows the number of people with multiple jobs. It is higher now than it was pre-pandemic but not by that much. The growth during the Biden administration has mostly been catching up to where we were three years into the Trump administration.

What’s more, the chart suggests that the growth of multiple job holders is a long-term trend that is consistent with a strengthening labor market rather than a weakening one. Many people have multiple jobs because they can. The jobs are available, and people are taking them. When the economy is sluggish, as it was in the post-financial crisis years, fewer people hold multiple jobs because there are fewer jobs to go around.

A better way of looking at multiple job holders is as a share of the overall workforce. As the chart below shows, this is not especially elevated right now. In fact, we’ve only recently returned to the pre-financial crisis level, and we’re nowhere near where we were prior to the turn of the century.

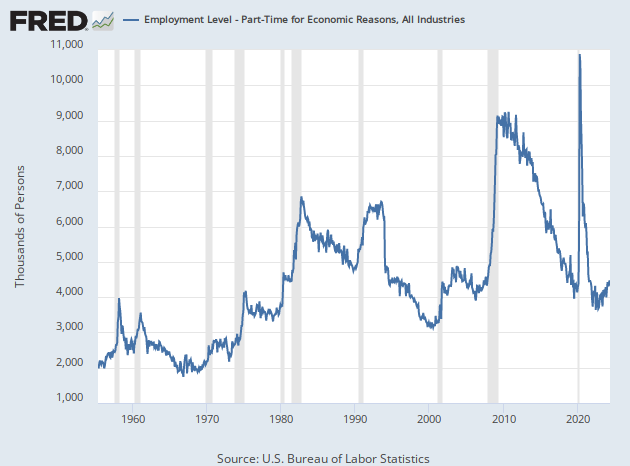

A related focus of labor market health skeptics has been the rise of part-time employment. The household survey in the March employment report, for example, showed that employment rose by 498,000—and all of that was accounted for by a 525,000 rise in part-time employment. This is part of a trend from full-time to part-time work that has been going on for at least two years. As of last month, the ratio of full-time employment to the available population dropped down to 50.1 percent, the lowest since November of 2021.

But this is not because people cannot find full-time work. The government describes people who would like to work full-time but cannot because of inadequate employer demand for their labor as “employed part-time for economic reasons.“ Of course, nearly everyone works for “economic reasons.” What the phrase means in this context is that the economy is insufficient to provide a full-time employment opportunity for the worker, so he or she is only working part time.

As the chart below shows, this number is not elevated. It is, in fact, close to its prepandemic level, which was the lowest in a decade. The economy is doing very well supplying full-time jobs to those who want them.

The growth of voluntary part-timing—what the government calls working part-time for “non-economic reasons”—likely reflects the shift to gig work, the growth of remote work, and older workers who want to supplement their income but not take on a full-time job. It likely also reflects a tighter labor market giving workers more control over their hours than they have had in decades. The boss may want his workers to show up full-time, but many workers are just fine with twenty hours on the clock.

The bigger picture is that neither the growth of multiple jobholders nor part-time jobs in an indicator of economic weakness. Quite the opposite. These developments suggest the labor market is very strong right now and likely to support robust economic growth in the near future.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.