A Song of Rates and Recession

Winter is no longer coming.

The phrase “winter is coming” is the motto of the Stark family in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Fire and Ice series and the Game of Thrones television program it inspired. It is a warning of hard times ahead and the inevitable return of the long winters known in the fictional land of Westeros.

Yet, in the realm of the Federal Reserve and monetary policy, the anticipated economic chill prompting rate cuts seems to be thawing before our very eyes.

The False Winter of Leading Indicators

The Leading Economic Index has been sounding the alarms of an impending financial winter for two years. On Monday, the Conference Board released the reading for January, showing the twenty-second consecutive decline. That’s the longest streak of falling readings for the gauge since the global financial crisis and the third longest streak on record.

Yet in a twist, the Conference Board now says the predictive barometer no longer indicates a looming recession. Instead, it now sees the indicators pointing to a slowdown to zero growth but not an actual contraction.

Larry Summers, who correctly warned that inflation would result from the Biden administration’s aggressively expansive American Rescue Plan in 2021, recently pointed out that there is a “meaningful” chance that the Fed’s next move is not a cut but a hike. This is a position we have taken at Breitbart Business Digest, arguing that the market’s obsession with when the Fed will cut is overlooking the risk that the Fed may not cut at all or may end up hiking.

“The assumption that inflation was headed down to 2% in a tranquil, healthy, real economy has certainly been called into question by these data,” Summers said in an interview with Bloomberg Television’s Wall Street Week.

Monetary Policy Is Not as Tight as It Looks

Former New York Fed President Bill Dudley argued in a Bloomberg Opinion piece on Monday that recent economic data suggests the current stance of monetary policy may not be as tight as is commonly thought:

Maybe monetary policy isn’t all that tight. That is, maybe the neutral, inflation-adjusted interest rate — the level that neither stimulates nor damps growth — is higher than Fed officials’ estimate of 0.5%, meaning that the current federal funds rate is less restrictive of growth. I think this is right: Large and chronic fiscal deficits, together with public subsidies for green investment, have pushed up the neutral interest rate. If so, the Fed should hold rates higher for longer.

This perspective challenges the clamor for rate cuts, suggesting the economy may require higher interest rates for longer if inflation is to be sustainably brought down to the Fed’s two percent target.

It’s a view that we have defended here and appears to be shared by Neel Kashkari of the Minneapolis Fed.

It is still possible that the economy could unexpectedly weaken enough to justify a rate cut this year. It’s impossible to have lived through the last three decades without the knowledge that unforeseen economic developments can come at a great cost.

But both national and global economic and geopolitical developments are moving in the other direction. Fiscal policy in the U.S. looks like it will remain expansionary at least through the November election. The war in Ukraine shows no signs of abating—although one cannot rule out an attempted “October surprise” by the Biden administration to declare peace in the region. The attacks on merchant vessels in the Red Sea continue to disrupt global shipping. Each poses the risk of putting upward pressure on inflation.

The Banner With the Outdated Device

Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, is still waving the banner of rate cuts.

This would seem to get things exactly backward. If the economy is producing full employment under current interest rates, why would the Fed need to cut? Zandi seems to believe that rates just should be lower, and therefore the Fed should cut unless there is a strong reason not to.

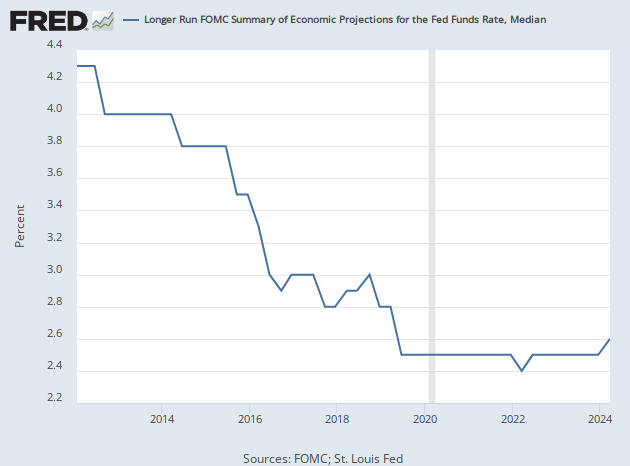

It’s true that the Fed’s own projections show that it thinks the long-term policy rate is 2.5 percent. But the Fed only started projecting that as the long-term policy rate in June of 2019. Ten years ago, the Fed was projecting a long-term rate of four percent. Perhaps the economy is just returning to a place where “normalized” rates are just higher than the Fed thought they were in the year before the pandemic hit.

The January FOMC meeting, where the Fed opted to bide its time, was a declaration of sorts—a refusal to bow to the pressures of the moment without “greater confidence” that inflation would retreat to its target. Nothing in the recent economic data can plausibly be thought of as inducing more confidence that inflation is headed down to two percent.

In Game of Thrones the Starks turn out to be right. Winter comes. But it takes a very, very long time to arrive. Someday the economy will fall back into a recession. But there are very few signals that day is approaching soon.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.