Economists Expect Little Growth Next Year

How soft will the soft landing be?

Economists have turned much more optimistic about the economy in recent months. The average probability of a recession over the next 12 months assigned by the business and academic survey conducted each quarter by the Wall Street Journal slipped to 48 percent from 53 percent in the July survey and 61 percent in April.

Yet growth is not expected to be particularly robust. In fact, some economists expect less growth next year than they did in prior surveys, probably because they are no longer expecting the economy to be rebounding following the widely-expected 2023 recession that never materialized.

The median expected growth rate for 2024 fell to one percent, according to the Wall Street Journal survey, down from 1.3 percent in the prior survey. The average growth expectation is 0.98 percent, down from the prior average of 1.26 percent.

The most recent survey of professional economists by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia is a bit more optimistic. It has the median growth expectation at 1.7 percent for 2024, which is actually an improvement from the 1.3 percent growth expected in the prior survey.

The forecasts of Federal Reserve officials have followed a similar trajectory, tilting slightly more positive. In the Summary of Economic Projections released back in September—the last time the Fed let us peak inside their beautiful minds—the median projected for real gross domestic product growth in 2024 was 1.5 percent, up from 1.1 percent in the prior set of projections. (Interestingly, however, the range of projections got wider, with the bottom of the range falling to 0.4 percent from 0.5 percent and the top increasing to 2.5 percent from 2.2 percent.)

Bank of America takes a dimmer view, currently projecting the economy growing just 0.6 percent next year.

What all of these projections have in common, however, is that they are forecasting a steep slowdown over the coming months. The economy grew at an annualized rate of 4.9 percent in the third quarter, so even the most bullish projections have the economy growing at less than that pace next year.

Slower growth is also expected to cool down the labor market. The median expected unemployment rate by the end of next year in the Wall Street Journal survey is 4.4 percent. The median for June of next year is 4.2 percent. The median projection of Fed officials is 4.1 percent at year-end. The Philly Fed’s survey, which looks at the full-year average rather than the year-end level, is 4.1 percent.

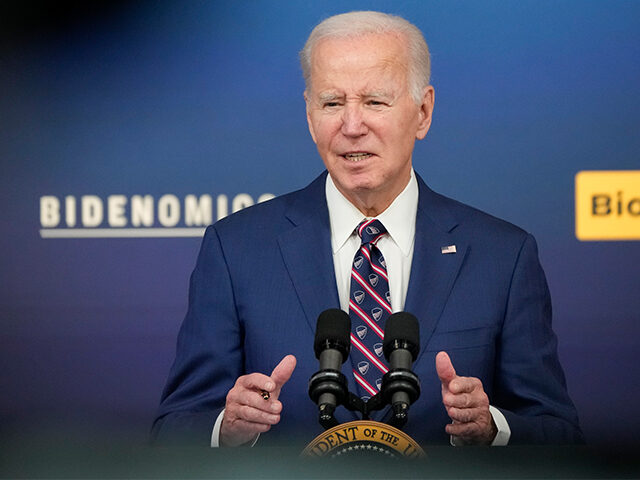

The Democrats’ Understandable Panic

It’s no wonder the Biden administration, the president’s re-election campaign, the Democrat Party, and the establishment media (we’re sorry if that list seems redundant) are in a panic over Biden’s recent polling results. The economy is expected to get worse next year. Even though it will likely skirt a recession, growth will be relatively sluggish and joblessness will likely be higher.

It’s not just the professional economists who expect things will get worse. Fifty-two percent of the public says the economy is getting worse, according to the latest poll from the Economist and YouGov. While there’s a partisan skew here—19 percent of Democrats say things are getting worse vs. 80 percent of Republicans—independents are pessimistic, with 60 percent saying things are getting worse.

The downturn could come at a particularly unwelcome time for Biden’s re-election chances. Data suggests that voters make their decisions about whether to reward incumbents with another term based on conditions one year to six months prior to an election. This means that even if the Biden administration were able to convince voters to buy into its long-term vision for the economy—an unlikely prospect—it wouldn’t help. What really matters is the conditions in the year prior to the election.

Why do voters put so much emphasis on the election-year economy? Political scientists have many theories. One notion—let’s call it the forgetful voter theory—is that voters just have trouble accurately remembering economic conditions of past years, and so they make their evaluation based on current conditions. Another idea might be called the years of work theory: voters recognize that it takes years for a president’s policies to effect the economy, so they focus on the last year of the current term as the one most likely to exhibit conditions produced by the incumbent’s policies.

A decade or so ago, research into this question indicated that a more sophisticated version of the forgetful voter may be the right explanation. Under this theory, voters use the election year economy to judge incumbents because present conditions are easily available, and voters feel confident they can use them as a substitute for the entire experience of the last few years. Instead of trying to evaluate the whole period, voters just use the past year as a heuristic.

This might not be all bad news for Democrats or all good news for Republicans. It at least suggests the possibility that if voters are less unhappy with the economy in six months—perhaps because inflation keeps falling—they will be more willing to look past how rotten the first three years of the Biden administration have felt. But it also suggests that a more sluggish economy could hurt Biden’s re-election chances.

One implication of this is that the most important political data that will emerge over the next few months is likely to be economic data about growth, employment, and inflation.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.