A Shock from JOLTS

The economy appears to have accelerated in the second half of the year, defying expectations that the interest rate hikes of the past 18 months would by now be a drag on growth.

The latest evidence comes from the fiery job vacancy figure in the August Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS. This showed that employers increased the number of job openings by 690,000 from the last day of July through the last day of August, bringing the total number of vacancies up to 9.61 million.

This is an indication that corporate America sought to ramp up hiring at a breakneck pace as the summer of 2023 came to a close. The best explanation is that this happened when business leaders finally became convinced that we were not headed into a recession in the near future. The consensus view very quickly flipped from expecting a slump to expecting a so-called “soft-landing.”

Wall Street completely missed the surge in vacancies. The consensus forecast was for openings to actually decline in August, down to 8.75 million from the original estimate for July of 8.83 million. The highest estimate in the Econoday survey called for a rise to 8.9 million. Which means that the August figure exceeded even the most bullish calls on JOLTS.

We also got a significant revision to the July figure to 8.92 million. If you use the original estimate, the August increase was 780,000. The “beat” over expectations was 860,000. In short, the labor market was much hotter than almost anyone thought going into September.

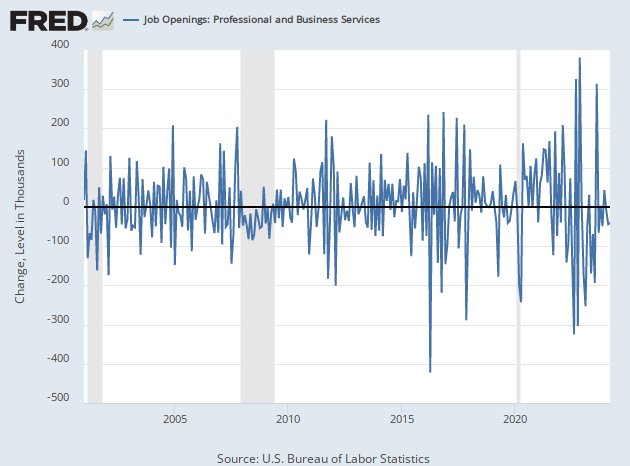

The largest part of the increase came in white-collar jobs. Professional and business services added an incredible 509,000 job openings. That is by far the single biggest monthly increase in records going back to 2001. On a long-term chart, it almost vanishes at the margin.

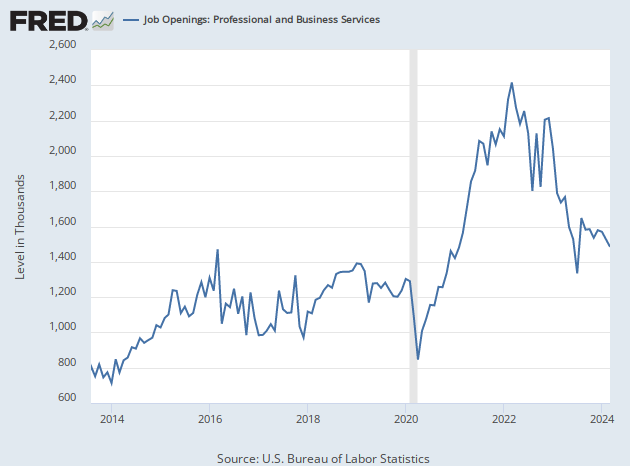

If we zoom in to cover just the last three years, you can see the increase a bit more clearly. What stands out in this chart is that the August openings far exceeds anything seen even in the post-pandemic hiring boom.

The rise is so extreme that some Wall Street analysts are dismissing it as noise or perhaps even the result of a survey error. Yet as tempting as it is to dismiss outlier figures, when viewed in the context of recent openings, it does not seem implausible.

The chart below shows the level of openings over the past ten years. What you can see is that while openings in professional and business services shot higher in August, this was only a partial reversal of the trend downward that had been going on since the start of the year. In context, this looks consistent with the idea that there was a sharp reversal in the view of corporate America that we were headed for a recession in the near future.

What if the Lags Were Short?

For over a year now, economists at the Federal Reserve and elsewhere have been telling us that what Nobel laureate Milton Friedman called the “long and variable” lags of monetary policy would eventually kick in and curb economic activity. What we have been seeing instead is evidence that the effects of the rapid rate increases of last year and the slower increases of this year may have run their course and that monetary policy is no longer significantly restrictive.

To put it differently, the lags may have been shorter than expected. The tightening of last year slowed the economy at the start of this year, although only down to a 2.2 percent pace of real growth for gross domestic product in the first quarter and 2.1 percent in the second quarter. Both of those are above the 1.8 percent that the Fed views as the long-term trend for the economy.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow model still sees the data as pointing to a 4.9 percent rate of growth for the third quarter, a blistering pace. Many on Wall Street have penciled in growth above three percent.

The housing market has gone berserk, with the highest mortgage rates in decades limiting the supply of existing homes. This is pushing up home prices, creating a wealth-effect that encourages consumer spending. It is also encouraging more home building and constructing spending, which increases employment and economic growth. At least in recent months, high mortgage rates have likely had the perverse effect of stimulating the economy.

Now the manufacturing sector, which was pushed into recession by higher rates, appears to be on the verge of recovery. The Institute of Supply Management and S&P Global purchasing managers surveys both show the sector is still in contraction—but just barely. What’s more, Tuesday’s JOLTS report showed manufacturers increased the number of job openings by 72,000 in August. While that is not a record high, it is very close to the pre-pandemic record highs of 73,000 in March of 2012 and 84,000 in November 2005.

The Key Is the Money Supply

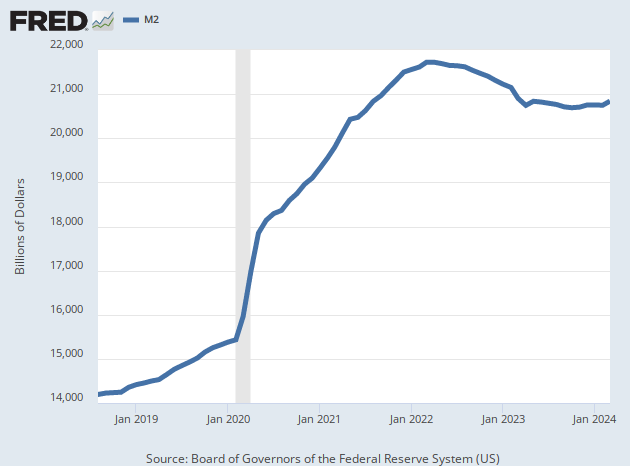

The key to understanding what is happening may be found in our old friend, the money supply. As we have pointed out in the past, the money supply—as defined by the seasonally adjusted M2—peaked in July of last year. Less well-known is that the decline in M2 ended in April and has since climbed back up a bit and then moved sideways. This does not look like a picture of an increasingly restrictive stance of monetary policy.

The economy is behaving, in other words, just as you would expect if the Fed took its foot off the brake pedal this past spring. Even though the Fed has raised rates a few more times since then, it has communicated that hikes are almost done with and that the Fed’s first move after this year is done will be a rate cut. The market has listened to this, and it has effectively eased monetary conditions.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.