The Housing Recovery Has Begun

It’s not exactly a self-evident truth, but it is a data-evident truth: the U.S. housing market is recovering.

Construction spending on single-family homes rose for the first time this year in May, data released by the Commerce Department showed on Monday. This was not just a tick or two up but a 1.7 percent increase after seasonal adjustments, more than reversing the last two months of falling spending.

On an unadjusted basis, this is actually the fourth consecutive month of sequentially increasing spending on single-family home construction.

While the construction figures are adjusted for seasonality, they are not adjusted for price changes. Back in the prepandemic era of longstanding low-inflation, that did not matter all that much. These days it can make a difference in assessing whether growth reflects actual increases in activity or just higher levels of nominal spending.

So, what do the inflation data tell us this time? The producer price index for construction materials for intermediate demand was flat in May, meaning prices were unchanged. They rose 0.1 percent in each of the previous four months after falling 0.5 percent in December. Prices for components for construction fell 0.2 percent in May. In other words, the May construction boom very much represents an increase in real activity.

Note also that construction payrolls rose by 25,000 in May, the second consecutive rise following April’s gain of 13,000. There are now over 300,000 more people employed in construction than at the prepandemic peak. After a brief downturn in March, payroll figures returned to a new peak in April and then broke that record in May.

The hiring spree in construction is not over. Job openings in construction at the end of April, the most recent data available, rose to 383,000 from 315,000 a month earlier. Although openings are below their all-time peak of 488,000 from last December, the current vacancy level is very high by historical standards. There are three times as many openings in construction as there are unemployed persons in the sector.

Housing Demand Is Booming

Sales of new single-family homes were up 12.2 percent in November to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 763,000. While this is below the pandemic housing boom peak of just over one million in the summer of 2020, it is above the prepandemic February 2020 level of 699,000. (The all-time high was 1.4 million, hit during the go-go years of the housing bubble in 2005.)

In June, the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) reported that after six consecutive months of improvement, home builder confidence moved into positive territory for the first time in 11 months. Traffic of perspective buyers in June has nearly doubled over the past six months, the NAHB data show.

The extremely lagging Case-Shiller home price indexes showed that home prices rose in April for the third-consecutive month. (Case-Shiller indexes not only come out with two-month delays but are based on three-month moving averages, so in June we’re reading about home price changes that took place between February and April.) Home prices in the national index rose a seasonally adjusted 0.5 percent in April and the 20-city index jumped 0.9 percent.

The National Association of Realtors said that 31 percent of homes sold in May fetched prices above what sellers were asking. Homes listed received an average of 3.3 offers.

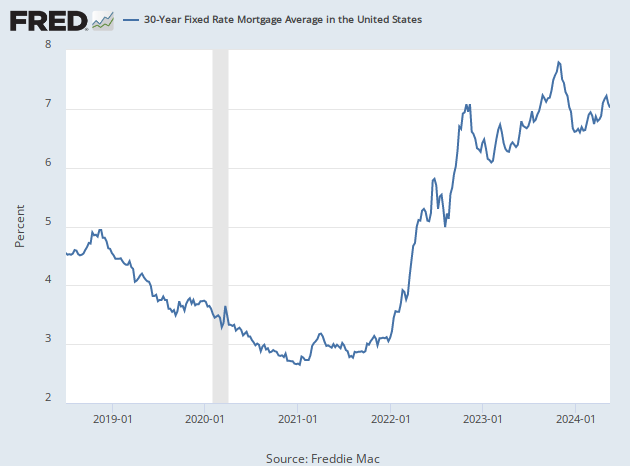

This is all the more remarkable because while mortgage rates have been volatile week-to-week, they have been above six percent and often closer to seven percent for several months. Whatever drag higher rates had on the housing market has greatly diminished.

Rates Stay Higher for Longer

The earlier-than-expected recovery in housing complicates the task of the Federal Reserve. Not only does it mean that the lagged effects of higher rates seem to have already come and gone, it means that the most interest-rate-sensitive sector of the economy—housing—is less interest-rate sensitive than thought.

What’s more, the ongoing rise in construction employment and job openings suggests that the sector will exert upward pressure on wages, hampering the Fed’s attempts to soften the labor market. As a result, rates are likely to stay higher for longer than the market anticipates.

The housing market is typically the Fed’s friend when it comes to tightening financial conditions. Going into the second half of 2023, that does not look to be the case.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.