Are we too optimistic about the U.S. economy?

The economy shrank in the first two quarters of this year. Ordinarily, two consecutive quarters of contraction are a clear indicator of a recession. The question of whether the economy was in a recession became controversial in part because of partisan politics and in part because of economic fundamentals.

The partisan politics are clear enough: left-wing economists and establishment media types did not want to admit that the economy had fallen back into a recession under President Joe Biden. One of the key claims of the Biden campaign had been that the Trump administration had wrecked the economy with its “bugled” response to the pandemic. This made it very difficult to admit that the economy had entered into another recession under the Biden administration.

The truth, of course, is that the economy did extraordinary well despite the pandemic, in large part because of the economic policies the Trump administration adopted very quickly after the pandemic hit. These were not conventional Republican or even conservative policies. They involved massive amounts of government intervention in the economy to stave off what would certainly have been a prolonged downturn. The idea—advanced repeatedly by Biden and his then Democrat rivals in 2020—that Trump could have managed the pandemic response in a way that would have led to a sunnier economic outcome is belied by the fact that Europe’s downturn was much worse.

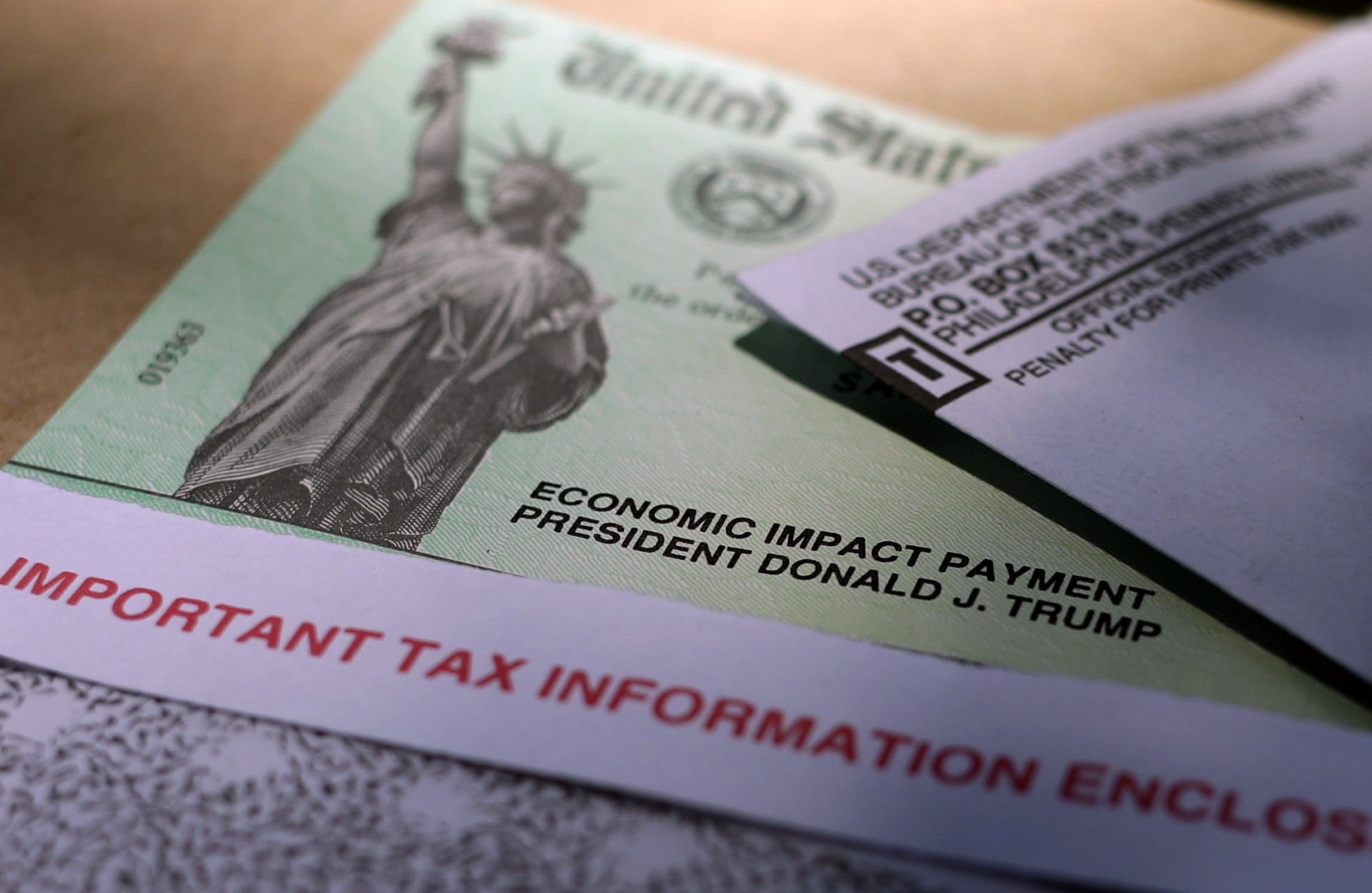

President Donald J. Trump’s name is printed on a stimulus check issued by the IRS to combat the adverse economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on April 23, 2020. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

The fundamental case against seeing the U.S. economy as already having gone through a recession this year is simply that the labor market has proved extremely resilient. The economy contracted in the first half of the year, but employers grew payrolls by 1.8 million jobs. The unemployment rate fell from four percent at the start of the year to 3.5 percent in September. Total job openings were above a staggeringly high 11 million for the entire first half of the year. In the low-employment slog of the post-global financial crisis years, there was a lot of talk about a “jobless recovery”—in which the economy grew but unemployment stayed high. If the economy was in a recession in the first half of this year, it was a joblessness-less recession.

The economy appears to have returned to growth in the third quarter of this year despite fiscal and monetary policy tightening. The housing market has definitively fallen into a recession, but manufacturing has remained surprisingly robust and consumer spending has held up better than expected. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNOW indicator sees third-quarter growth at 2.9 percent. In a recent note to clients, Bank of America said it sees the economy growing at an annualized rate of 2.5 percent in the third quarter, thanks to stronger-than-expected consumer spending in September and August. Note, however, that even that growth will not be enough to stop the economy from contracting on a four quarter basis. Bank of America still sees the economy shrinking slightly compared with the fourth quarter of last year.

Our baseline forecast has been that the economy would enter an unquestionable recession next year. Unemployment would rise as the Fed continues to hike rates, the economy would contract significantly, home prices would stall and even decline in overheated markets, manufacturing would go into a severe retreat, and services sector demand would plunge. That seemed a pretty pessimistic outlook and was certainly worse than the soft-ish landing or milquetoast recession that Wall Street has been anticipating.

(iStock/Getty Images)

But perhaps we are too optimistic. The downward revision to potential growth by the staff of the Federal Reserve at least implies the possibility that the economy will be even worse than we expected. What’s more, our assumption has been that the Fed would stay the course in its fight against inflation. If that proves to be wrong—as a Nouriel Roubini emphatically insists in a recent interview with a Bloomberg podcast—the economy could be in for an even rougher time. In Roubini’s scenario, the economy enters into a severe recession, the Fed “wimps out,” inflation becomes entrenched, and a financial crisis occurs. We know that Roubini is called “Doctor Doom,” but none of his scenario seems far-fetched.

For now, at least, our expectation is for a bad downturn that begins at the end of this year or early next year. But the risks are heavily weighted to the downside. We expect things will get bad, but we will be preparing for things to get worse.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.