Just how unbalanced is the labor market?

This question has become one of the biggest debates in economics today. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his fellow officials at the Federal Reserve see the labor market as extremely unbalanced, with demand for workers far outstripping supply. Others, however, have argued that the Fed’s view of labor markets is distorted in a way that exaggerates demand.

Powell has been very clear about his position for several months. Recall that he used to argue that the Fed might be able to bring down inflation without raising unemployment by very much by lowering the number of job vacancies. Initially, Powell seemed to have a great deal of confidence that an improving economy could bring workers off the sidelines, reducing vacancies by filling them. The unbalanced supply and demand of labor could be rebalanced upward.

He seems to have abandoned that view and now talks about the likelihood that the tightening of financial conditions will cause “pain.” But the underlying message is the same: demand for labor will need to fall to bring it back into balance with the supply of workers.

“The labor market is particularly strong, but it is clearly out of balance, with demand for workers substantially exceeding the supply of available workers,” Powell said in Jackson Hole last month.

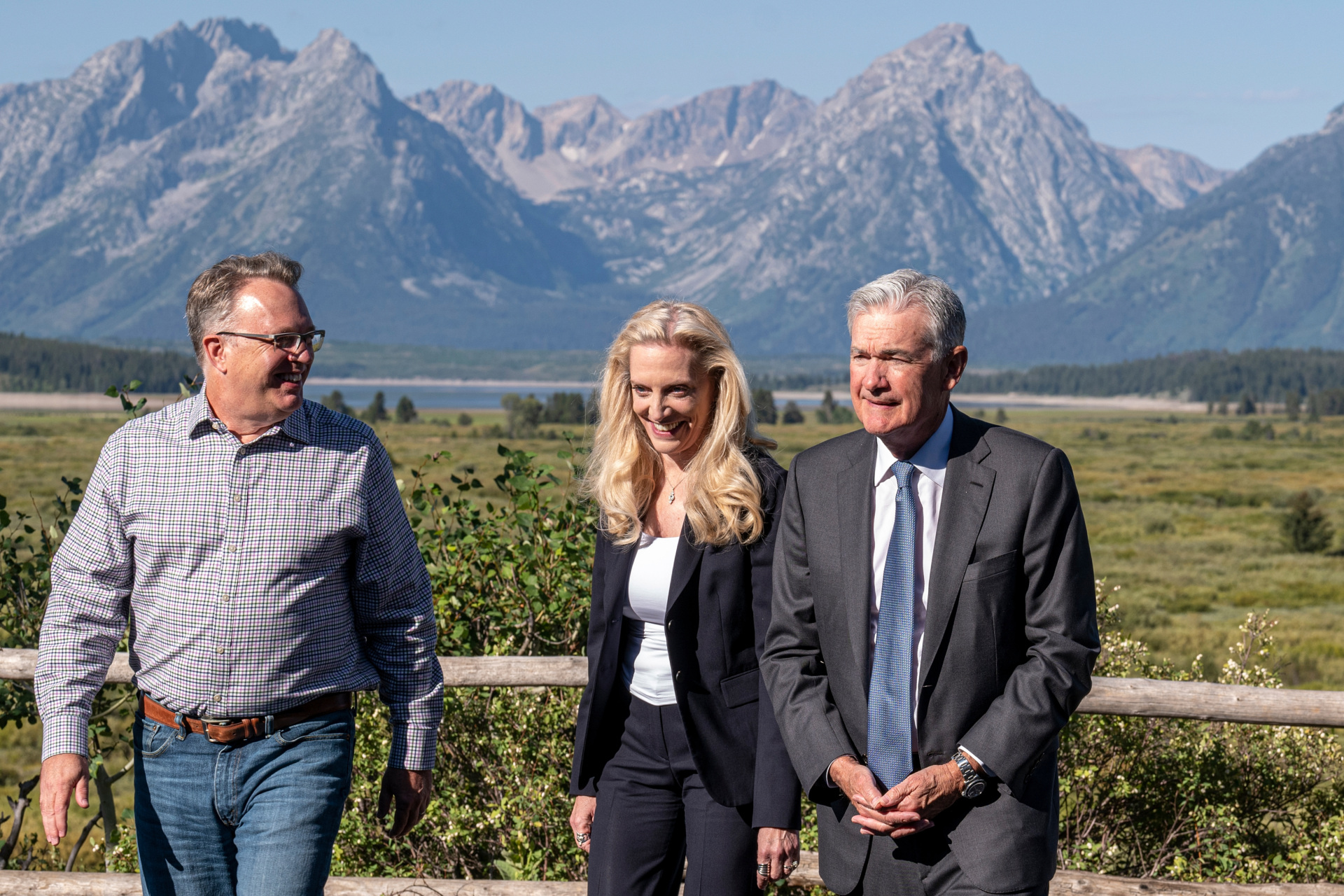

From right to left: Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve chairman; Lael Brainard, vice chair of the board of governors for the Federal Reserve System; and John Williams, president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, during a break at the Jackson Hole economic symposium in Moran, Wyoming, on August 26, 2022. (David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

In today’s remarks to a Cato Institute conference, Powell sounded the same note. “What we hope to achieve is a period of growth below trend which will cause the labor market to get back into better balance and that will bring wages back down to levels that are more consistent with 2% inflation over time,” he said.

The economic theory here is that job vacancies, as measured by the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), can be thought of as the unmet demand for labor, and the number of unemployed people can be thought of as the available supply of labor. The ratio of vacancies to unemployed people has become a central measure of the tightness of the labor market in academic economic literature.

The historical average ratio is around 0.6 vacancies to each unemployed person. Which means that we typically have more people looking for work but out of a job than we have jobs available. In other words, the normal situation for decades before the recent crisis was that we had too little demand relative to supply, we were beset with labor market slack. The all-time low for the ratio was 0.15 vacancies to each unemployed person hit in the wake of the global financial crisis. The all-time high, prior to recent years, was 1.5 in the “hot” labor market of the 1960s.

This led some economists to think that the soaring ratio of vacancies to unemployed people would likely peak somewhere around the 1960s peak, even though there was very little evidence that anything like this was happening. Indeed, the conviction that the ratio would decline was one of the key factors backing the claims in 2021 that inflation would be transitory. An economic research note from the San Francisco Fed in October 2021, for example, examined the inflationary impact of the American Rescue Plan. It argued the ratio had already peaked in 2021: “estimated impact of the ARP on inflation is meaningful, but it is still a far cry from the strong overheating of the 1960s.”

As you can see from the chart above, the ratio did not peak. It kept rising. In July of this year, the most recent data available, the ratio climbed back to the all-time high hit in March. Both are basically indistinguishable from two to one, meaning two vacancies for every unemployed person. That is around two-and-one-third times the historical average. It appears to indicate an extreme imbalance.

The extremity of this imbalance has led to some questioning among economists about whether it is real. Perhaps something has gone wrong with the way we measure job openings, these economists propose. A recent paper from Employ America makes a number of arguments against relying on JOLTS openings, including the idea that it has become easier to post job openings in the age of the internet. Certainly, a naive look at the number of job openings creates some room for skepticism. How could employers suddenly need that many more people?

Here’s the same graph but limited to accommodations and food services. It shows a huge explosion of vacancies in hotels and restaurants that peaked in January and has come down in recent months as people have been hired into jobs.

Before you accept these as evidence that the JOLTS data is overstating vacancies, keep in mind two things. First, there’s very little evidence that suggests the pandemic should have thrown off the counting of openings. Certainly, the kind of technological improvements—online postings of job openings, mainly—predated the pandemic; so they cannot be used to explain the explosion of openings.

Jan Hatzius, the Goldman Sachs economist, doubts the problem is with the data. “We have not really found a lot of evidence that the meaning of a job opening is dramatically different relative to 10 or 20 years ago. And if you look at the official series as of a year and a half ago, it wasn’t out of line with history. And technologically, a year and a half ago wasn’t that different from where we are now,” Hatzius said in an interview with Bloomberg’s “Odd Lots” podcast.

Second, openings rise not just because employers want to hire but because employers want to hire faster than they can find workers. That is, there is already a supply element embedded in the openings number. If fewer employees want to work, openings will rise even if underlying demand for labor does not. Here is a chart of the total number of people working in accommodations and food services plus the total number of openings. We might think of this as a chart of the underlying demand for labor for the sector.

What we see is not that demand spiked strikingly higher but that it returned to around where it was before the pandemic. Employers in restaurants and hotels are not looking for far more workers, they’re looking for around as many as they were looking for before the pandemic. Openings are high because fewer workers are taking those jobs. You can see this by looking at the chart of total employment in restaurant and drinking places.

So demand is high relative to supply, but the constraint is on the supply side. In some ways, this is a story we already knew. The labor force participation rate is below its prepandemic level, which was already low compared with what we saw before the global financial crisis. Why it is lower now is one of the other great economic questions of our times.

The evidence points to the idea that Powell is right to look at the labor market as severely imbalanced. Demand relative to supply, however you measure these, is extremely high. It’s unlikely that this is resolvable without a recession bringing down demand because there are few signs supply can be brought up by much. Even if the labor force participation did inch up in August, it’s not going to increase fast enough to bring down inflation. And the recession may have to be more severe than many expect because demand for labor will have to be brought down below prepandemic levels in many sectors of the economy, including in restaurants, bars, and hotels.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.