Remember when greed was allegedly driving up the price of gasoline?

At least as far back as November of 2021, President Joe Biden was claiming that gas station owners were overcharging motorists for gasoline. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm has complained about a “disparity” between gas prices and oil prices. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and some fellow Senate Democrats proposed a windfall tax on oil companies. As recently as last month, President Biden implied gas station owners were being unpatriotic by not bringing down prices. Countless Democratic politicians said profit grabbing was behind high prices.

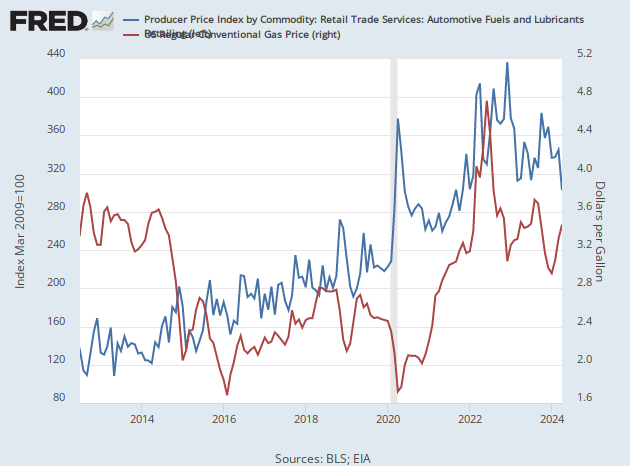

So what happened in July as gas prices crashed 16.7 percent, according to the Producer Price Index released Thursday? Did the gas station owners suddenly become less greedy? Had Biden convinced them to lower the price they charged at the pump to “reflect the cost you’re paying for the product?” Did reduced greed bring down the price of gas—and therefore the overall level of inflation?

Not quite. The Producer Price Index not only tracks prices paid to businesses for goods and services, it also tracks the mark-ups charged by retailers and wholesalers. What’s the difference? When a cabinet maker buys wood from the mill, we can track the price of the milled wood. That goes into the Producer Price Index under the lumber index. Looking these up in the tables created by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we can see that hardwood lumber fell 1.4 percent in July, the second straight month-to-month decline, and is up 5.3 percent compared with a year ago. The price of the cabinets gets reported under the household furniture category, up 2.2 percent compared with June and 12.3 percent compared with a year ago. This is all a pretty straightforward tracking of price changes.

What happens when a cabinet gets sold to the wholesaler or retailer? The price is typically increased even though nothing more is added. The government attributes this market to a service it calls “trade services.” Instead of measuring the price charged, which is what the rest of the Producer Price Index measures, it tracks the change in the margin. To carry through with our example, in July the index for furnishing wholesaler trade services rose 2.3 percent. Compared with a year ago, it is up 21.3. The index tracking retail trade services for the furniture business actually slipped one-tenth of a percent in July but is up a massive 30.8 percent from a year ago.

So what happened to gas station trade services while the price of gas was crashing? In July, the margins of gas retailers soared 12.3 percent. That is four times as much as the three percent rise in June, when gas prices were hitting record highs. The May surge in gas prices saw margins fall 21.2 percent. In other words, rising prices of gasoline are not caused by overcharging, and falling prices are not the result of gas station owners charging prices closer to what they pay. In fact, history suggests the opposite. Gas station profits tend to improve as prices fall rather than due to gouging when prices are rising or already high.

Food Inflation Matters a Lot

Speaking of the Producer Price Index, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said on Thursday that this measure of inflation fell 0.5 percent in July compared with June. While critics of the administration have focused on the fact that year-over-year inflation figures are still sky-high, the July monthly figures in the Producer Price Index should not be overlooked. They are the most recent data when the annual figures are really just a collection of what we already knew.

So what do they tell us? The headline figures—unchanged for CPI and down 0.5 percent for PPI—are not really new information because they mainly reflect something else we know: gasoline prices are down by a lot. The CPI index for all items excluding energy rose 0.4 percent, indicating that prices continued to rise in the month. The PPI index for final demand excluding energy was up 0.2 percent, and the index for final demand goods minus energy was up 0.4 percent.

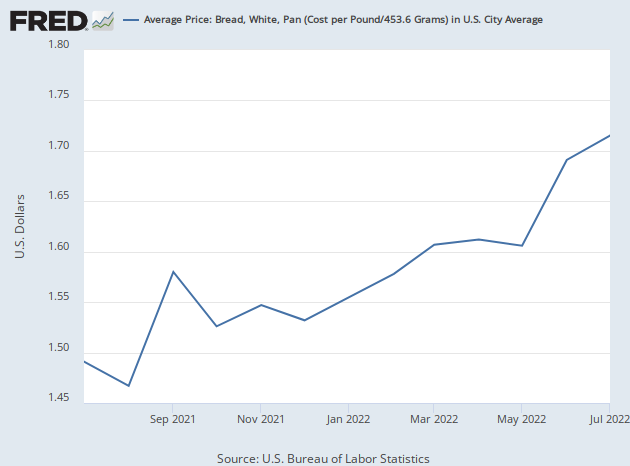

A big driver of these numbers was food. The CPI index for food at home rose 1.3 percent in July. The consumer food index in PPI rose two percent. Both numbers were above the June figures, showing that food inflation accelerated in July. The annual figures, by the way, were up the most since 1979 for CPI and 1974 for PPI.

Three years ago, a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research—the folks who get to tell us when a recession officially begins and ends—found that consumers base their outlook about future prices on trends they see while grocery shopping. Using information from a survey of 90,000 households about the prices and quantities of non-durable goods in each household’s consumption basket, the researchers found that expectations of future inflation varied substantially with the household’s exposure to different grocery-price changes. The price changes that most influenced inflation expectations were “those goods households purchased frequently, such as milk and bread, rather than the goods on which households spent a larger part of their budget, which is the implicit underlying assumption in most aggregate measures of inflation such as the core CPI.”

The most recent consumer price data tells us that milk prices rose 0.1 percent in July and are up 15.8 percent for the year. Bread prices jumped 2.8 percent and are up 13.7 percent for the year. Breakfast cereals rose two percent in July and are up 16.4 percent since a year ago.

If the NBER study is correct—which we suspect it is—then consumers are likely to look past the July headline and core CPI numbers and expect a lot more inflation to come.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.