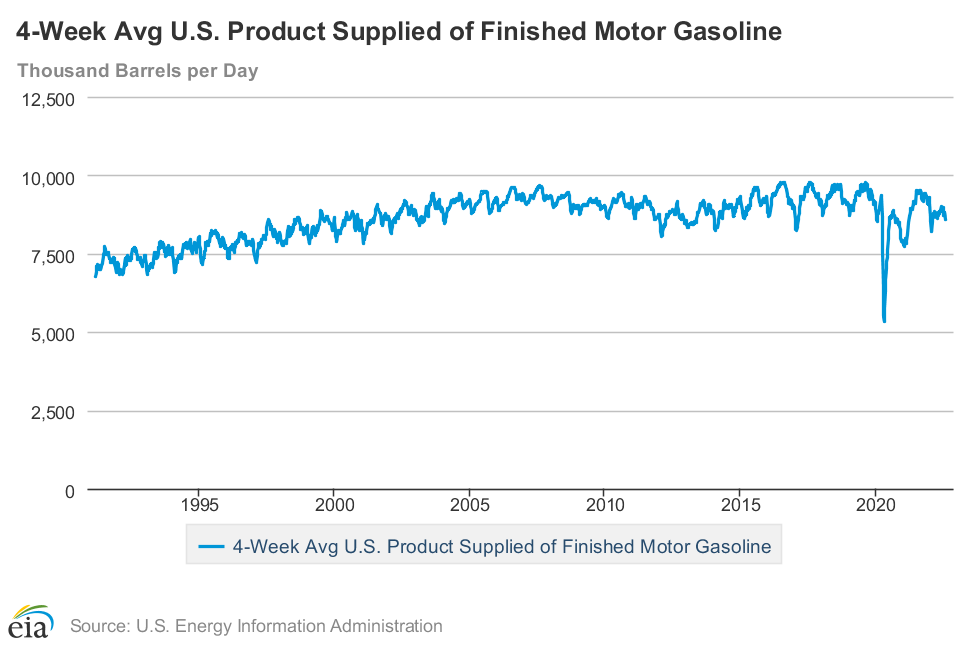

Is it possible that Americans are driving less than they did in the summer of 2020, when many Americans were working from home and operating under pandemic travel restrictions?

The Energy Information Administration said that the four-week average of U.S. gas deliveries had fallen 7.6 percent, down more than one million barrels a day below what was typical pre-pandemic. This is below the levels seen in the summer of 2020. The report helped push the price of gasoline futures down 11 percent on Wednesday. West Texas Intermediate crude oil fell down below $90 a barrel on fears of falling demand. Brent Crude fell three percent on Thursday to $93.90.

The story that’s been circulating to explain the decline is one of demand destruction, the notion that Americans became so fed-up or tapped-out by high gas prices that they’ve begun to cut back on driving. Supporting this idea are polls showing that many Americans are driving less because of high gas prices. A poll released on July 6 by Rasmussen, for example, found 66 percent of Americans had reduced driving. A poll published on July 25 by the American Automobile Association found 64 percent of Americans had changed their behavior because of high gas prices, 88 percent of whom said they were driving less.

There’s plenty of reasons to be skeptical, however, that demand has fallen that far. In the first place, the EIA implied demand figure is based on deliveries to gas stations rather than gas pumped into cars. There’s some anecdotal evidence that gas station operators may be keeping their own orders low as prices fall, trying to avoid buying gas at a price higher than the market will bear in a few days. With gas prices falling for 49 consecutive days, this becomes an attractive strategy. It’s not really a sustainable strategy, though, so at some point the EIA numbers would have to show a demand surge.

Jan Stuart, global energy strategist at Piper Sandler & Co., described the EIA numbers as “very crooked” in an interview with Bloomberg TV. In his view, the way the EIA numbers are compiled “leaves significant room for error.”

“We’re supposed to believe that in July, in the middle of the driving season, we’re only using 8.6 million barrels a day. That would be down a half a million barrels a day from May. That would below the Covid low of 2020,” Stuart said. “So we asked all the refiners. We asked all the retailers. We asked everybody that reported earnings this season. Every single one of them tells you that their sales are not down materially from even pre-Covid days. Some report record high sales.”

Similarly, Bank of America’s Doug Leggate reports that the refiners he follows are “not seeing it.” They saw softer than expected demand around the July 4th holiday, when gas was close to $5 a gallon, but strong demand later in the month as prices kept falling. Indeed, it seems odd that demand would be so much lower as gas prices approached $4 than they were at $5. Leggate thinks an “adjustment factor” used by the EIA could be responsible for the apparent crash in demand.

Patrick De Haan of Gas Buddy says that his data, based on pump sales, showed an increase in sales.

There have been plenty of raised eyebrows about the timing of the EIA data, which came just after OPEC+ slapped President Joe Biden in the face with a minuscule 100,000 barrel increase in global oil quotas. Could the agency be cooking the books? That’s extremely unlikely. A lot of data has proven unreliable through the pandemic, lockdowns, and reopening, with unusual volatility throwing off measurements that depend in part on models informed by historical patterns.

Is the Fed Getting the Jobs Done?

The employment situation report will hit the tape at 8:30 a.m. tomorrow. July is expected to see 250,000 jobs added to nonfarm payrolls, a big drop from the better-than-expected 372,000 in June. The unemployment rate is expected to hold steady at 3.6 percent. Average hourly earnings are forecast to rise by 0.3 percent, matching the June gain.

The jobs report will test whether the Fed’s back-to-back rate hikes have begun to cool the labor market. The JOLTS figures released this week showed that job openings came down by more than expected in June, with a particularly deep decline in vacant positions in retail, implying some cooling of a still-red hot job market. More jobs than expected may somewhat quell fears of an imminent recession, especially if there’s a rise in average hourly wages. That would, however, spark fears that inflation is still rising. Slightly lower than expected may be just what markets want, suggesting inflationary pressures softening. Much lower? Sound the recession alarms.

Build Back China

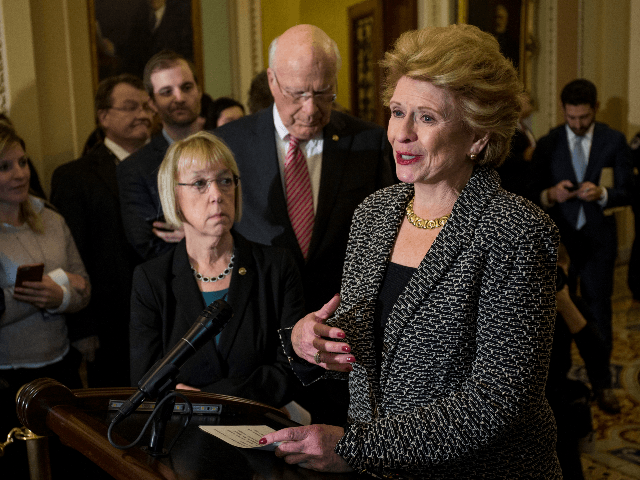

The cynically named Inflation Reduction Act—which will do nothing to reduce inflation—looks like it may wind up even worse than when it was hatched into this world by Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY). The big Detroit automakers have enlisted Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) to push for the evisceration of one the bill’s only silver linings: rules designed to bolster U.S. critical mineral supply chains and prevent electric vehicle subsidies from enriching China.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) speaks to the press on December 11, 2018, in Washington, DC. (Zach Gibson/Getty Images)

The current bill prohibits electric vehicle tax credits for cars whose batteries contain any critical minerals from China. Stabenow and the automakers are crying foul, saying that this will mean their customers will not be able to make use of the credits because—they claim—they cannot build cars that run on China-free batteries. They say they’ll get around to building capacity outside of China eventually, but in the meantime they want to be able to get subsidies for their Chinamobiles. They haven’t been hesitant to claim that any delay in getting people into EVs with China-sourced batteries will worsen climate change. If you don’t want taxpayer subsidies for China batteries, it means you hate the planet.

If anything, this response highlights the need for this provision to take effect immediately. The automakers are admitting that they are not only incapable of building EVs without China, they’re saying attempting to develop the capacity would take years. Which means that as we move toward renewable energy and electric vehicles, China will gain increasing leverage over our entire automotive manufacturing sector.

If Stabenow’s change makes it way into the bill, they should just rename it Build Back China.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.