We are getting a clearer picture of why the board of Twitter agreed to the takeover offer of $54.20 a share from Elon Musk. The short version is that the social media company’s bankers told them that this was as good as it was going to get.

Musk’s bid was treated as a joke when it was first made in part because it was a joke. The last three digits of the offer are a reference to a numerical signal for marijuana. Twitter’s board responded with a poison pill that continued the joke, creating a right for shareholders to acquire shares for $210 that were worth twice that much.

It was also highly unusual for Musk’s offer to be presented as his “best and final” offer. That’s the kind of language a more traditional unsolicited bidder might use toward the end of a prolonged negotiation, not an opening offer. It almost invites rejection by signaling that there’s no room for dealmaking, nothing for the existing board to do to try to increase the return to shareholders. That’s kind of humiliating for the existing board members, and starting a negotiation by humiliating the other side is not typically thought of as the most prudent opening move.

There is, however, some precedent for this sort of thing. Back in April of 2007, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp made an unsolicited bid of $60 for Dow Jones, the owner of the Wall Street Journal. Although Murdoch did not publicly declare that this was his best and final offer, it was. Despite months of back-and-forth, Murdoch never increased the offer. To be fair, it was a 67 percent premium over where the shares had been trading. Nonetheless, it does stand as a precedent for an unsolicited and unchangeable bid for a media company, albeit a much smaller one. Dow Jones cost News Corp just $5.6 billion.

What made Musk’s bid a lot less jokey was the fact that he lined up $25.5 billion in committed bank financing for the deal. While we predicted Musk would have no problem financing the deal, the speed and apparent ease with which this came together surprised some analysts and commentators. So on Tuesday, many are still asking how on earth could these 11 or so Wall Street banks really trust Musk with that kind of money for a deal that he had said he was interested in for reasons that are not primarily economic?

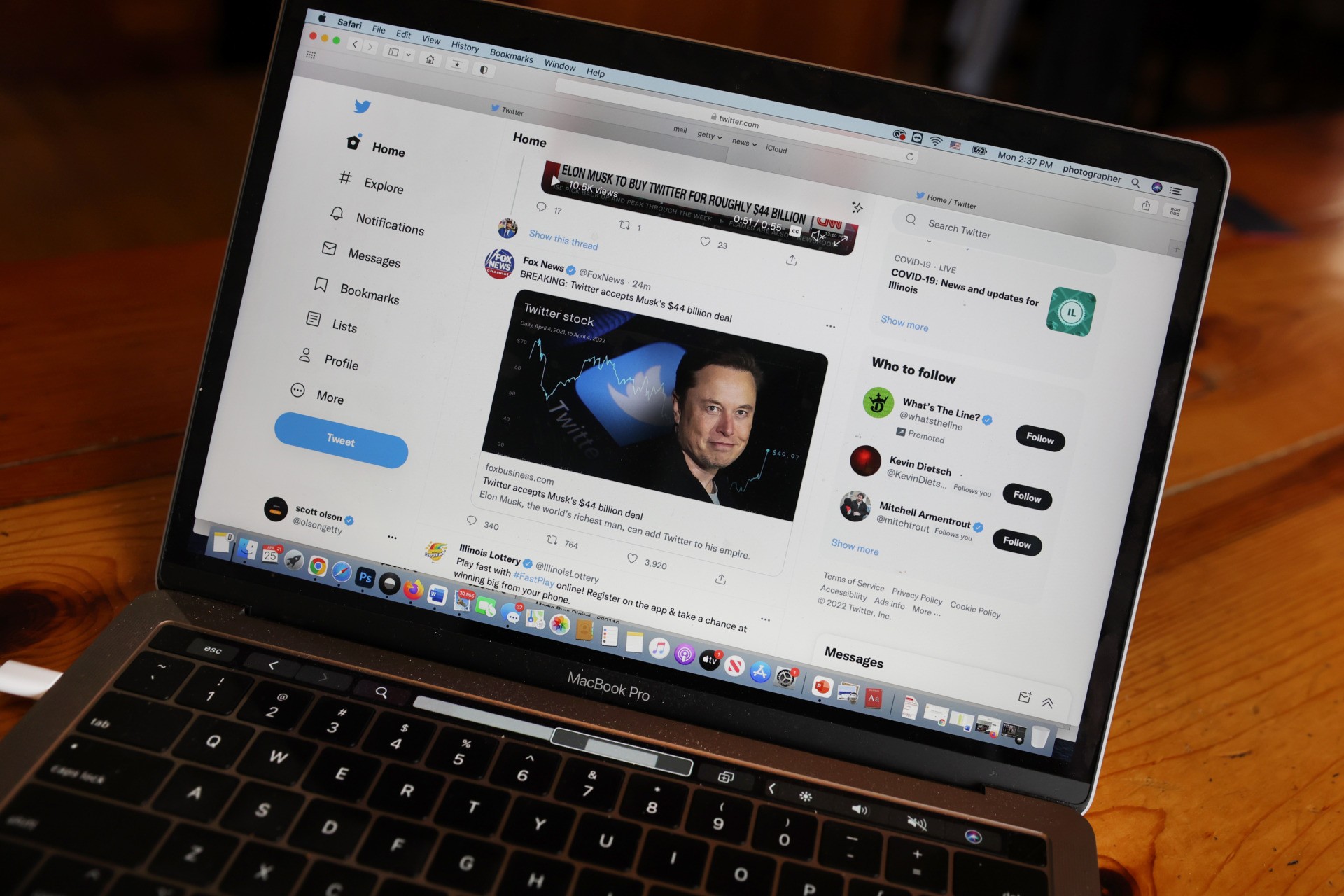

News about Elon Musk’s bid to takeover Twitter is seen on a Twitter scroll on April 25, 2022. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

There are really two things to know about how Musk got the “funding secured” here. The first is that the debt package is not very risky. Only $13 billion is a traditional leveraged buyout loan package secured by the assets of Twitter. Six billion dollars of that debt is designed to eventually be taken out by an even amount of secured bonds and unsecured bonds. So unless you think Twitter was massively overvalued prior to Musk’s involvement, that part of the debt is massively over-collateralized.

The rest of the debt is in the form of margin loans against Musk’s Tesla’s stock. By most calculations, Musk’s Tesla stock and vest stock options are worth more than $200 billion. Under the bylaws of Tesla, Musk is allowed to borrow up to 25 percent of the value of his stock or around $40 billion. Lending Musk $12.5 billion against his Tesla stock is an easy call.

Which brings us to our second point: banks want to be in the business of doing business with Elon Musk. He’s the wealthiest man in the world and reportedly finances much of his personal expenses with margin loans against his Tesla stock. So he is personally a font of fees for bankers. What’s more, Tesla is a huge issuer of debt and equity securities, all of which generate fees for bankers. In the first half of 2021, for example, Tesla issued $2.3 billion in stock through secondary offerings, generating around $28 million in fees for Wall Street. He controls SpaceX, the third most valuable privately held company in the world, and bankers dream of the fees its IPO would generate. When Musk calls up Morgan Stanley to see about raising money for something he wants to do, you can be sure they are going to move heaven and earth to get it done. A good relationship banker could build a dynastic personal fortune doing nothing but answering Musk’s phone calls and making sure checks get written.

The main reason the board capitulated to Musk’s humiliating offer, however, is that the company’s own bankers told them that they should take the deal. The board would have turned to its advisers—in this case, Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan Chase—and asked them to do a valuation analysis to assess the fairness of the offer. Normally, bankers can be counted on to tell the board what they want to hear. If the board wants to sell, the bankers will say an offer is fair. If the board wants to resist, the bankers will say that the company has a path to a much higher value so refusing to sell is in the interest of shareholders. That did not happen here. We do not know the details, but the assessment from the bankers must have been pretty bleak because it resulted in the board very quickly accepting Musk’s offer.

We’ll learn more in the weeks ahead when the company files its proxy statement describing the background of the deal. But it’s safe to say that Musk won Twitter because he is willing to pay more than what it is credibly worth. $54.20 might have been a pot joke, but it was also an offer the board could not afford to turn down.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.