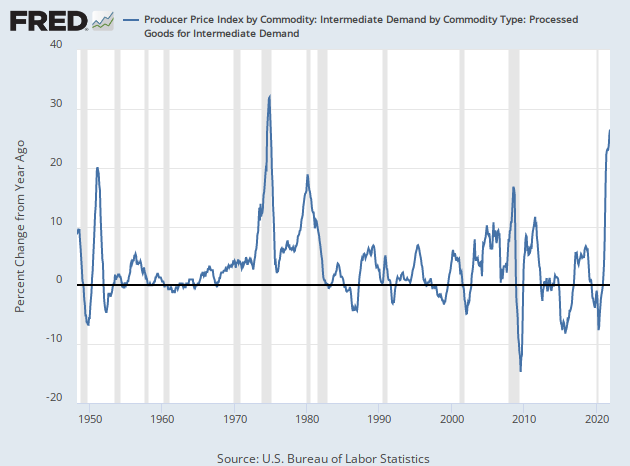

The record-shattering 9.6 percent rise in producer prices indicates a startling level of inflation inflicting the U.S. economy.

Things are even worse once you get beyond the headlines. Further out on the supply chains, prices are rising even more rapidly, suggesting that product shortages and even more inflation are yet to come.

When you look at goods that are processed by U.S. manufacturers for sale to other businesses, such as an appliance manufacturer selling to a retailer or a software maker selling to an digital game store, prices are up by more than 26 percent.

The headline figure for the Producer Price Index records prices received by domestic businesses for “final demand” goods and services, those that are sold to households, governments, exported, or to businesses as capital investments. It is the category that most closely resembles the more-familiar Consumer Price Index, which measures prices paid by consumers and, unlike the PPI, includes imported goods.

The PPI report also measures goods sold for “intermediate demand,” those sold from one business to another along the chain of production of goods and services. When a manufacturer of appliances sells to a retail store, that gets counted in the intermediate demand category, while the sale of the appliance to the household sector is final demand (and also gets counted in the CPI gauge). Services are also sold into the market for “intermediate demand.” Corporate lawyers, consultants, advertising, and investment bankers are examples of business-to-business services.

This creates visibility into how prices are flowing through the economy. Often when inflation builds up in the intermediate stage, it flows through to the final demand stage later as companies seek to pass along price increases. Alternatively, when production becomes too costly, businesses can cut back on production, which can lead to shortages or higher prices. But unless consumers are willing and able to pay more, it’s often difficult for businesses to pass along increased costs, resulting in smaller profits.

The index for processed goods for intermediate demand jumped 1.5 percent in November, which is a slowdown from the 2.4 percent rise in October. This is no longer a case of the volatile food and energy categories pushing up the index. In November, over half the increase was for materials excluding food and energy. The intermediate foods and feeds index actually dropped 0.2 percent. The energy index climbed 3.6 percent.

It’s the year-over-year number that is really eye-catching. Prices for intermediate processed goods are up 26.5 percent, the largest 12-month increase since December 1974, when the index rose 28.9 percent.

This inflation is widespread. Prices for materials and components for manufacturing are up 42 percent year over year. Materials for durable goods manufacturing saw their prices jump 59.8 percent. Prices on components for durable goods rose 9.7 percent. Nondurable materials were up 36.2 percent and components 19.5 percent.

The construction industry is being hit by much higher costs. Materials prices are up 13.5 percent Component prices are up 27.1 percent.

Inflation is running even hotter in unprocessed goods, which includes crude oil, grains, iron and steel, and other raw materials. Prices rose 4.8 percent in November and are up 52.5 percent over 12-months. Over 80 percent of that is energy prices. If you subtract energy prices, unprocessed goods for intermediate demand saw prices rise 21.8 percent.

The intermediate demand category also gets broken down into four stages of production, giving us even more insight into where the inflationary pressures are hitting hardest. Stage one is the earliest stage of production, often the transformation of raw materials or extraction of fuels, that gets sold to businesses in “stage two” of the production process. The fourth stage is the penultimate stage, akin to what people think of as “wholesale,” before products reach “final demand” for sales to households, governments, export, or capital investment by businesses.

At the wholesale level, the price of goods was up 1.4 percent in November and 17.5 percent year-over-year. Excluding food and energy, prices were up 16.1 percent. At stage three, goods prices were up 33.6 percent over the 12-month window and 34.6 percent once you exclude food and energy. At stage two, goods prices are up 57.3 percent annually. Once food and energy is subtracted, prices here are up 28.7 percent. At stage one, goods prices are up 33.2 percent annually and 29.4 percent excluding food and energy.

This indicates that there is a lot of inflationary pressure built up in the pipelines of the economy. That does not necessarily mean it all gets passed through to consumers. Ultimately consumer prices depend on the ability and willingness of consumers to pay. Studies have shown that intermediate PPI changes do not directly predict changes to consumer prices, although earlier stage prices do often predict later stages in the PPI.

This suggests that the Fed may have more trouble taming inflation next year than is anticipated. Even if backups at ports and shipping constraints lift, this will not directly affect the prices measured in PPI, which excludes imports by only counting prices paid to domestic producers. Substitution of domestic goods with imports, however, could help tame PPI inflation over time.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.