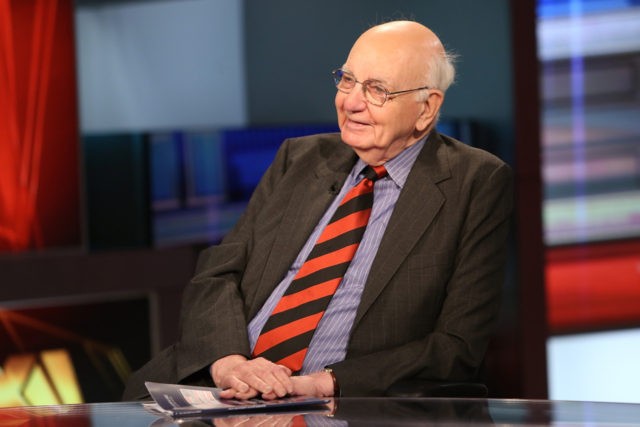

The world’s greatest inflation fighter has died.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker died Sunday at age 92. When he took the top job at the U.S. central bank in 1979, consumer prices were rising 13 percent. They rose by the same amount the following year.

Interest rates soared as Volcker sought to tame inflation by tightening the money supply. The federal funds rate rose as high as 22 percent in 1981, plunging the economy into two recessions, one starting in 1980 and lasting six months and another starting in 1981 and lasted 18-months.

President Ronald Reagan was critical of Volcker and the Fed. Many of Reagan’s advisers believed that Volcker was endangering their economic agenda of tax cuts and regulatory reform by keeping monetary policy too tight. Reagan nonetheless reappointed Volcker, who had been appointed by Jimmy Carter, as Fed chair in 1984. He served in that role until 1987.

When Volcker left the Fed, inflation had come down to 1.86 percent.

The 1980 recession lasted just six months. But it was followed by a deeper and more painful downturn that took hold in July 1981. This second Volcker recession, brought on by high interest rates that made it expensive for businesses to borrow and for Americans to buy homes or tap lines of credit, endured for 18 months and sent unemployment up to 10.8 percent in November and December 1982, the highest level since the Great Depression.

In the midst of it, Volcker was vilified by the public. Homebuilders put postage stamps on bricks and on two-by-four wooden planks and mailed them to the Fed to protest how super-high interest rates had wrecked their businesses. Auto dealers, stuck with lots full of unsold cars, did the same with car keys. Angry farmers, struggling with high debts, drove their tractors to Washington and blockaded the Fed’s headquarters.

But the pain eventually paid off. Inflation receded. Once it did, Volcker’s Fed began lowering interest rates. And the economy bounded back strongly enough for President Ronald Reagan to declare the arrival of “Morning in America’’ on his way to a landslide victory in the 1984 presidential election. Volcker left the Fed in Aug. 11, 1987, succeeded by Alan Greenspan.

The Volcker-led victory over inflation is widely credited with beginning what economists call the “Great Moderation’’ — more than two decades of mostly steady economic growth, relatively low unemployment and modest price increases. The Great Moderation ended with the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Volcker had spent most of his career in the public sector — at the Treasury Department, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the Fed board in Washington.

Six-foot-seven and perpetually rumpled, Volcker favored cheap cigars and bad suits. John Connally, a slick Texan who was Volcker’s boss at the Treasury in the early ’70s, once threatened to fire him if he didn’t get a haircut and improve his wardrobe.

After leaving the Fed, Volcker took on assignments as a troubleshooter. He ran a commission to investigate what Swiss banks did with the assets of Holocaust victims during and after World War II. The United Nations assigned him to look into allegations of corruption in a UN program to provide food aid to Iraq.

After the financial crisis of 2008, President Barack Obama recruited him as an economic adviser. Volcker pressed for restrictions on banks’ ability to trade in financial markets with their own money, rather than their clients’, and to invest in private equity and hedge funds. The regulations, known as the “Volcker Rule,’’ were included in a far-reaching financial overhaul bill Congress passed in 2010. Volcker had little sympathy for big banks in the wake of the financial crisis, which required a taxpayer bailout of big Wall Street firms. He dismissed claims that deregulated financial institutions deserved credit for coming up with innovative products and services.

The only useful financial innovation he’d seen in years, he said, was the ATM.

–The Associated Press contributed to this report.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.