President Donald Trump is right. America needs more workers.

But if his advisers are telling him that this means America needs higher levels of immigration, they are misleading the president. America does not need to import workers. We have plenty of potential workers who were sidelined by the Great Recession and globalization.

In the first two years of the Trump presidency, America created two million jobs. The unemployment level fell to an astonishing 3.7 percent in September, the lowest level in decades, and it has averaged 4 percent over the past year.

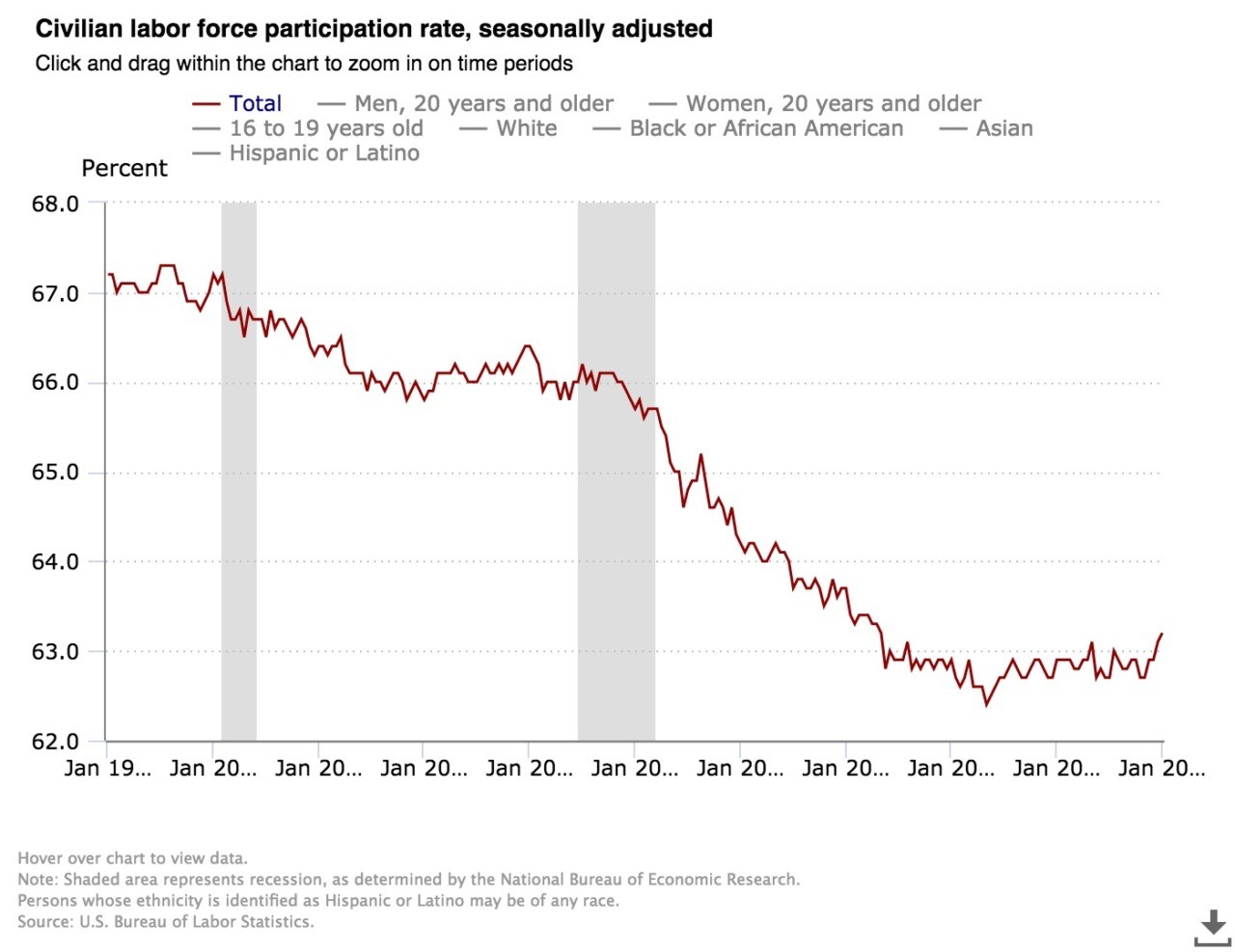

The official unemployment rate, however, only includes Americans looking for work. It overlooks more than 90 million Americans who are officially out of the labor force. The civilian labor force participation rate is now just 63.2 percent—down from more than 66 percent prior to the Great Recession.

Even when adjusted for America’s aging workforce and more working-age Americans attending college, participation is low. Just 82.6 percent of Americans between the ages of 25 and 54 were counted in the labor force, according to the most recent figures from the Department of Labor. That’s a full percentage point lower than it was in the late 1990s, the last time unemployment was this low:

In his recent testimony on Capitol Hill, Fed chair Jerome Powell called the low level of labor force participation a “very troubling concern.”

“There are lots of people, millions of people, who are out of the labor force and in a perfect world, in a better world, would be in the labor force,” Powell said. “We want the economy to grow, and we want that prosperity to be widely spread. Labor force participation gets both of those things almost better than anything.”

President Trump knows that millions of Americans are out of work. In his first address to a joint session of Congress in February 2017, Trump said, “We must honestly acknowledge the circumstances we inherited. Ninety-four million Americans are out of the labor force.”

To be sure, since the election, we’ve made some progress in drawing Americans back into the labor force. More than 2.1 million people joined the labor force in 2018. The participation rate is up a full percentage point compared with a year ago, as is the participation rate among those prime working age Americans between 25 and 54.

But wage growth has lagged behind expectations and historical levels. Average hourly earnings grew 3.2 percent in 2018. After adjusting for inflation, that amounted to an increase of just 1.7 percent.

Compare that with the 4.2 percent average wage growth right back in 2001—when the workforce participation rate was higher than 66 percent.

The low level of wage growth indicates that despite the howls from corporate America about worker shortages, employers are not vigorously chasing workers with higher pay. Absent rapidly rising prices for labor, cries of a shortage ring hollow. All available data show a tight relationship between workforce participation and wage growth.

“Businesses love to say we’ve got shortages — it’s this historic worker shortage. Well, show me the money,” Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said last year.

When the labor force is swamped with demand, prices rise and attract additional supply—just as conventional economic textbooks suggest. But when wage growth is weak, workers stay on the sidelines.

Now, employers like Apple, whose chief executive Tim Cook was seated beside President Trump at the meeting of the White House’s Workforce Advisory Panel on Wednesday, are unlikely to find workers with the skills they need among Americans currently out of the workforce. But Apple could hire and train experienced workers away from other firms, creating job openings that can be filled by less experienced workers, and so on, eventually creating openings for those out of the workforce.

Think of it like an economic ladder. As an American worker climbs the ladder, she frees up the rung where she used to stand. The worker behind her climbs up a step, freeing another rung. As long as there are workers not yet on the ladder, there is plenty of room in the economy for moving up.

Importing skilled labor disrupts the climb. Instead of raising wages and employing more Americans, companies may import workers and stick them in the empty slot on the ladder. Those at the bottom do not move up. Those off the ladder never climb on.

One reason many employers prefer foreign workers is that U.S. residency is a subsidy—a form of compensation for the worker that the employer does not pay for. Visas are a form of corporate welfare that enables businesses to pay foreign workers less than they would need to pay a homebrewed worker to do the same job.

The size of this subsidy is enormous. Visa workers are often permitted to bring spouses. Even unmarried visa workers can win new work permits by marrying someone currently living abroad. Any children born in the U.S. will be citizens, who will eventually be able to sponsor their parents for citizenship.

From an economic perspective, U.S. residency is part of the compensation foreign workers receive for accepting employment from a company like Apple. Americans, however, need to be compensated in dollars or benefits—forms of compensation that subtract from the bottom line. Immigration keeps labor costs down.

It is no wonder, then, that the president’s Workforce Advisory Panel—which has only one representative of the private workforce compared with 15 CEOs—told the president we have a worker shortage and urged him to abandon his policy of hiring Americans first. This protects their bottom lines.

Employers have been using this line for years. Bloomberg recently quoted a 2011 Federal Reserve report that cited companies in the Richmond region complaining about the lack of skilled workers.

“Finding skilled workers continued to be a major concern,” the Fed’s November 2011 beige book said.

Unemployment was 8.6 percent. Since then, America has added 18 million jobs, according to Bloomberg.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.