The Republican tax overhaul plan currently under construction in the White House and Capitol Hill includes a mandatory tax on the overseas earnings accumulated by U.S. corporations, according to three people briefed on the plan.

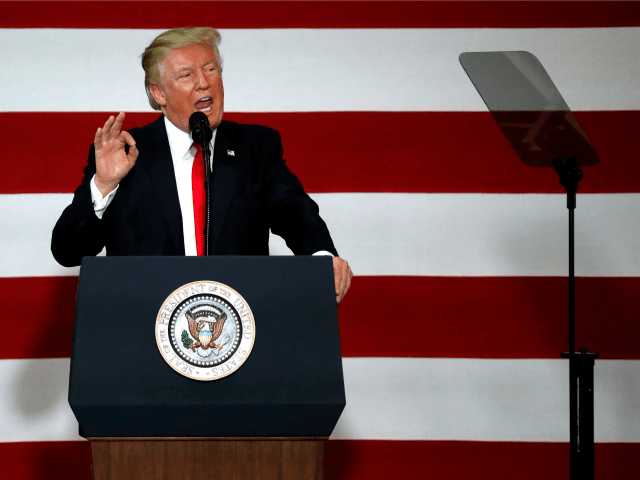

In his Missouri speech, Donald Trump singled out tax rules that encourage American companies to keep profits earned around the globe in the accounts of their foreign subsidiaries.

“By making it less punitive for companies to bring back this money, and by making the process far less bureaucratic and difficult, we can return trillions and trillions of dollars to our economy and spur billions of dollars in new investments in our struggling communities throughout our nation,” Trump said.

While many heard this as a call for a temporary tax holiday for overseas cash similar to one adopted during the Bush administration, sources briefed on the current plan–which is still being finalized–say the Trump plan will include an important and novel feature: the tax holiday will be mandatory.

Officially, the U.S. taxes multinational companies based in the U.S. on their earnings worldwide. When companies pay a lower tax on earnings abroad, they incur a tax liability for the difference between the foreign tax and the U.S. tax rate, which is the highest in the developed world. But because the taxes on foreign earnings do not come due until the profits are handed over to the U.S. parent company, an event known as repatriation, many large U.S. companies choose to leave the income in the foreign subsidiaries.

In popular jargon, this money is hoarded or “stashed abroad.” In reality, however, much of it is in U.S. bank accounts or invested in U.S. securities, including U.S. Treasury bonds. But because it has not been transferred to the parent company, it is considered to be held overseas as an accounting matter. This means it cannot be invested in the U.S. or used to pay dividends or buyback shares.

In an effort to encourage companies to repatriate these funds, Congress adopted a temporary tax holiday in 2004. Companies were offered a chance to repatriate funds under a 5.25 percent tax rate, much lower than the normal 35 percent corporate rate, subject to certain limitations and exceptions. Some 834 companies decided to take advantage of the holiday, bringing home more than $300 billion in profits.

Despite this, the Bush era program is now widely deemed to be a failure. Despite rules that attempted to discourage companies from using repatriated funds to buy back stocks, studies have shown that much of the repatriated funds were used for just this purpose. What’s more, critics say the move encouraged companies to keep profits earned after the holiday overseas in anticipation of a future tax holiday.

The plan currently under development differs because it would deem all foreign profits to have been repatriated, in effect removing the tax deferral for overseas profits. The deemed repatriated profits, however, would be subject to a preferential “transition” rate and would be payable over a number of years. This would raise revenues for several years as companies paid down the new tax liability, helping “pay for” lower corporate rates.

Those familiar with the plan say Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin hinted at the deemed redemption aspect in an interview Thursday with Steve Liesman of CNBC.

“We have one of the highest rates in the world. We have this concept of worldwide but with deferral. So it encourages companies to move their business offshore and keep their profits off shore,” Mnuchin said.

The deemed redemption tax can be seen as a way of “wiping the slate clean,” one person familiar with the matter said. It could be a step toward moving toward a territorial tax system, in which U.S. companies are no longer taxed by the U.S. government for profits overseas, although the complexity of moving to “territoriality” is still causing headaches by those developing the tax plan, the person said.

“What is most important is that we end up with a competitive rate and that we end up with a territorial system and that’s what we heard from literally hundreds and hundres of business people,” Mnuchin told CNBC.

The revenue-raising aspect of the “mandatory holiday” is one of the things that makes it particularly attractive, according to a person familiar with the matter. Although over the long-term, lower corporate tax rates would likely mean lower revenue, a ten-year repatriation window would likely be scored by congressional budget watchers as increasing revenues over the next ten years.

The longer time period would also give corporations more time to strategically deploy the profits, lower the incentive to use them for short-term financial engineering in the form of dividends and buybacks, one person said.

Proponents in the administration point out that coupling the repatriation holiday with a lower corporate rate should dampen the incentives for companies to once again start accumulating foreign profits in anticipation of a future holiday.

People briefed on the matter stressed that the plan is still a work-in-progress and might change significantly in the coming weeks as it gets “socialized”–meaning discussed with members of Congress.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.