Turkey’s fractious opposition parties united on Monday behind a single candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu of the Republican People’s Party (CHP).

If the six-party coalition holds together through the June 18 election, Kilicdaroglu has a real shot at unseating the increasingly authoritarian and Islamist incumbent, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Kilicdaroglu, 74, is a low-key career civil servant who went right into the Turkish Ministry of Treasury and Finance after graduating from college. He actually won a “Bureaucrat of the Year” award in 1994. He parlayed his reputation as an honest administrator and corruption fighter into a seat in the Turkish parliament in 2002, the same year Erdogan took the top office.

CHP is the party of Turkey’s legendary secular reformer, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, and Kilicdaroglu is running on a platform of breaking down the authoritarian, nationalist, and Islamist power structure forged by Erdogan, who explicitly despises Ataturk’s vision of limited secular government compatible with Western values.

Turkish army tanks parade in front of a giant banner with a portrait of the founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, during Victory Day celebrations in Ankara on August 30, 2008. (ADEM ALTAN/AFP via Getty Images)

Kilicdaroglu looks quite a bit like India’s revolutionary leader Mahatma Gandhi – a rather more flattering comparison than the individual Erdogan is sometimes teased for resembling – and his supporters applaud the quiet but firm determination he has shown in debates with Erdogan’s fiery nationalist AKP party.

“He is nice and very calm – a little too calm. Kemal never raises his voice, he never shouts. You can’t even have a decent argument with him. The fact that he is so quiet sometimes really drives me crazy,” Kilicdaroglu’s wife Selvi once remarked in an interview.

One of the six parties backing Kilicdaroglu for president, the Good Party, almost dropped out of the coalition because they thought he was too boring and would get steamrolled by Erdogan’s hot-tempered populism. The Good Party was wooed back into the alliance by promising its leader Meral Aksener one of the two vice-presidential slots.

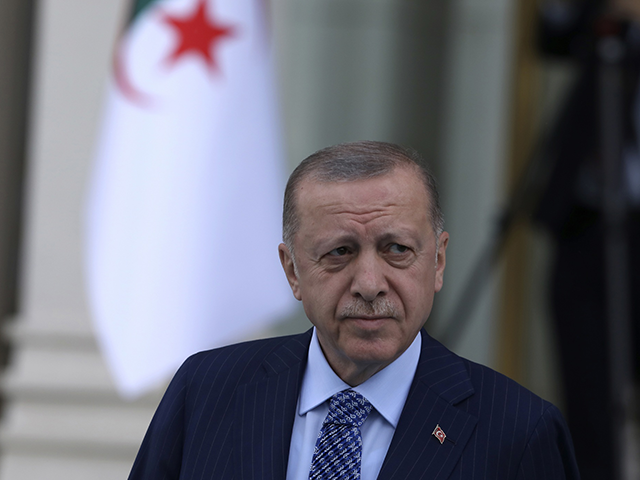

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan arrives for a ceremony, in Ankara, Turkey, May 16, 2022. (Burhan Ozbilici, File/AP)

Kilicdaroglu even remains unruffled after assassination attempts, of which he has survived several. When he attended a funeral for Turkish soldiers killed fighting the Kurdish separatist group PKK in April 2019, the crowd pushed him around, punched him in the face, cornered him in a house, and considered either lynching him or burning the house down around him. A fellow CHP politician recalled Kilicdaroglu inviting everyone to tea after emerging from his refuge and asking his companions not to “blow things out of proportion.”

To the considerable ire of CHP members, Erdogan’s government was even more chill about the attempted lynching than the famously relaxed victim. Only one suspect was briefly detained, even though Erdogan’s administration is normally eager to take action against the PKK. The head of a nationalist party allied with PKK blamed Kilicdaroglu for provoking the crowd into beating him up. CHP responded by accusing the government of setting Kilicdaroglu up for murder by depriving him of police protection and sending agents to rile up the crowd.

The opposition coalition, dubbed the Nation Alliance, on Tuesday presented a 12-step agenda for returning Turkey to parliamentary government instead of Erdogan’s strongman presidency. The roadmap stipulates that leaders from the six allied parties will each hold a ministry position during the “transition period,” with the remaining ministry seats given to other parties according to their share of the vote. Kilicdaroglu pledged to consult extensively with Nation Alliance leaders as he breaks down Erdogan’s rule-by-decree system.

The Nation Alliance is debating how to respond to overtures from the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), a pro-Kurdish party that Erdogan has threatened to ban over alleged links to the separatist PKK.

On Monday, HDP co-chair Mithat Sancar said his party will not nominate its own presidential candidate and might be willing to actively support Kilicdaroglu if he meets with HDP leaders to discuss their concerns.

“Good luck with Kilicdaroglu’s candidacy! We look forward to his visit to talk to him at our headquarters. Our goal is democracy, justice and freedom. Basically, we want to talk about principles,” Sancar said.

The HDP is Turkey’s third-largest party behind AKP and CHP, so its support could be invaluable for overcoming Erdogan’s nationalist coalition. Unfortunately, it was locked out of the National Alliance by Aksener’s Good Party, which has nationalist leanings and distrusts the Kurdish bloc.

Aksener said on Tuesday that she didn’t mind CHP leaders holding “talks” with HDP, but she insisted the pro-Kurdish party “can never join the alliance or be given a ministry if we win.”

Aksener said her party would exit the alliance “for good” if Kilicdaroglu’s party courts HDP too ardently.

“I’m on the side of honesty and openness. If the CHP wants dialogue, they can have it but they cannot bring the HDP’s demands up to the alliance, not now, not after,” she said.

“Our red line regarding the HDP is the same as all Turkish citizens; it is respect for the integrity of the law, the first four articles of the Turkish Constitution and the emphasis on unity and solidarity in Turkey,” she said, referring to various charges of sedition and terrorism pressed against HDP and one of its leaders, the imprisoned Selahattin Demirtas.

A Nation Alliance leader grumbled to Daily Sabah on Tuesday that since HDP commands about ten percent of the Turkish vote, beating Erdogan without its support would be nearly impossible, and even with HDP in his corner, Kilicdaroglu is running neck-and-neck with Erdogan in the polls. Another Nation Alliance official told Reuters that HDP is so despised by the Good Party, and by some CHP voters, that it might cost the alliance almost as many votes as it would bring to the table.

Erdogan looks vulnerable after more than two decades in power due to public discontent over his response to the devastating earthquakes of February 6, which killed over 46,000 people in Turkey. Erdogan apologized for the slow government response at the end of February as he watched his poll numbers sink.

A girl walks near a tent beside collapsed buildings on February 13, 2023, in Hatay, Turkey. A 7.8-magnitude earthquake hit near Gaziantep, Turkey, in the early hours of Monday, followed by another 7.5-magnitude tremor just after midday. The quakes caused widespread destruction in southern Turkey and northern Syria and were felt in nearby countries. (Burak Kara/Getty Images)

On Monday, Erdogan vowed to make earthquake relief the sole focus of his government throughout the election campaign. He suggested the election might be moved up to May 14 to make the campaign season shorter.

“Usually, the election processes are damaging and can cast a shadow on relief efforts. But what Turkey needs is to focus on fulfilling the needs of the victims of the disaster,” Erdogan said.

“For us, the focus will continue to be the earthquake and recovering damages. We will not digest running an election campaign based on political polemics when 10 million people were affected by the earthquake that destroyed a part of the country,” he promised.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.