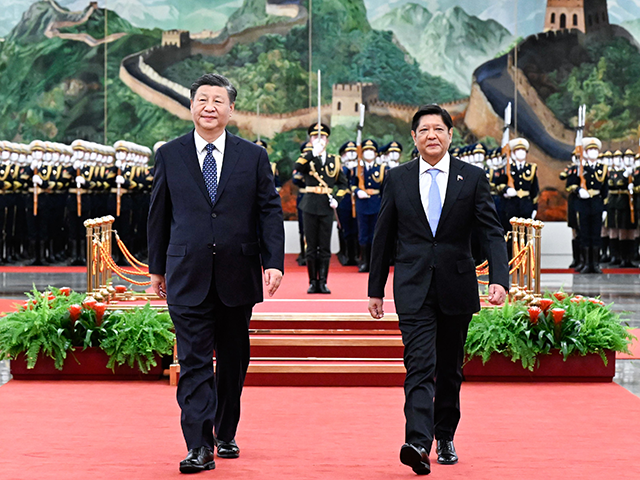

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., often referred to by his nickname “Bongbong,” made his first visit in office to China this week, holding meetings with dictator Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang.

The Marcos administration said the president planned to sign up to 14 bilateral agreements with the Chinese during his visit but insisted he would not give ground on Philippine territorial claims in the South China Sea.

The South China Morning Post (SCMP) on Wednesday said Beijing saw Marcos’ visit as crucial to stopping “a key member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations getting closer to the United States amid the heightened rivalry between Washington and Beijing.”

To that end, Xi reminisced about his previous meetings with Marcos and lavished praise on his father Ferdinand Marcos, the corrupt authoritarian ruler of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986.

For his part, Marcos included former Philippine president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, an old personal friend of Xi’s, as a surprise member of his entourage.

“They had a few minutes of recollecting the meetings that they have had, which I think helped the tone of the meeting,” Marcos said of Xi’s encounter with Macapagal-Arroyo.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., right, waves beside wife Maria Louise as they board a plane for China on Tuesday, January 3, 2023, at the Villamor Air Base in Manila, Philippines. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila)

In addition to signing a raft of China-Philippines cooperation agreements on commerce, infrastructure, and tourism, Xi proposed joint oil and gas exploration by the two countries in the contested waters of the South China Sea.

China claims almost the entire region, up to an arbitrary barrier invented by Beijing called the “Nine-Dash Line.” China’s claims were ruled illegal by an international arbitration court in 2016, but China routinely ignores the decision.

The Philippine government has competing claims with China in parts of the South China Sea, but Marcos, Jr.’s predecessor Rodrigo Duterte generally backed away from pressing those claims, citing the immense power imbalance between the Philippines and China.

Philippine officials said on Wednesday that while the tone of Marcos’ visit was cordial and constructive, he was more determined than Duterte to stand by Manila’s claims in what it calls the “West Philippine Sea.”

To that end, the Marcos administration ordered an increased military presence near the Spratly Islands last month after China began creating artificial islands in the Spratly archipelago. The Philippines has also lodged objections with China over its tactic of “swarming” disputed islands with so many boats that Filipino fishermen cannot access their traditional hunting grounds.

The South China Sea was also the scene of a tense encounter in November, when a Chinese coast guard vessel intercepted a Philippine naval craft and forcibly seized Chinese rocket debris it was towing.

“The issues between our two countries are problems that do not belong between two friends,” Marcos said optimistically when departing for Beijing on Tuesday.

China’s state-run Global Times trumpeted on Wednesday that all tension between China and the Philippines “collapsed on itself” during Marcos’ visit.

According to the Global Times, all of that tension was manufactured by hostile Western powers to bamboozle Marcos, and he realized China is his true friend as soon as he spoke to Xi. The Chinese Communist paper laid out what Marcos needs to keep saying if he wants to avoid trouble with his aggressive maritime neighbor:

First, mutually beneficial and win-win cooperation between China and the Philippines will be continuously promoted, which is the locomotive and engine leading the development of bilateral relations. Second, divergences in the South China Sea will be managed and controlled, and will be prevented to become a stumbling block of pragmatic cooperation, or a fuse of a crisis that could undermine peace and stability in the South China Sea.

In recent years, China and the Philippines have been meeting each other half way on these two themes, achieved fruitful results and reached leapfrog development. On the South China Sea issue, both sides made a lot of communication with good intentions, and did not let it become an obstacle to bilateral relations.

The Global Times leaned heavily into the idea that only the United States has a serious problem with China’s illegal territorial claims, which is a way of letting the Filipinos know they had better be ready to drop their own objections. The editorial let Marcos know that his desire to “balance” relations with Beijing and Washington would not be tolerated:

Marcos said that the Philippines adheres to independent diplomacy and will not choose sides. But for the Philippines and other countries in the region, it has always been a problem to soberly and wisely deal with the “coercion and temptation” from Washington.

Another Global Times editorial on Wednesday touted Marcos’ visit as proof that a “golden age” in relations between Beijing and Manila has begun, and “there is little room for outside forces like the U.S. to meddle in the South China Sea situation and interrupt the two countries’ efforts to promote common development.”

Both Global Times editorials repeatedly mentioned joint oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea, positioning it as Marcos’ payoff for backing away from the United States and getting out of China’s way in the Spratlys.

If he does not play along, the Chinese editorialists darkly hinted that Marcos would be blamed for scuttling the new golden age of China-Philippines relations, just as they blamed the administration of Benigno Aquino III in the 2010s for ruining an earlier golden age by deciding to “provoke China on the South China Sea issue and create a series of conflicts and tensions in the region to serve the U.S. strategy that aims to contain China and interrupt regional peace and stability.”

“The Philippines has learned from the past, and current leaders understand what their country can get from pragmatic and friendly cooperation with China, and what they would lose if they unwisely allow themselves to be used by Washington to contain China,” the Global Times asserted.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.