Whoever said “buy low, sell high” never said it to Jann Wenner.

The 71-year-old publisher markets his 50-year-old magazine, Rolling Stone, to potential buyers. The for-sale sign comes three years after the magazine portrayed a fraternity at the University of Virginia as a rape den.

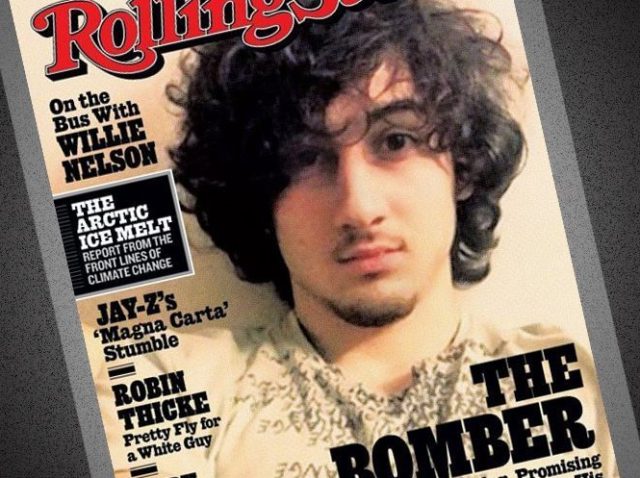

But its credibility, like its judgment, never inspired much confidence. Forty-three years before it placed Boston Marathon Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev sporting a dreamy teen-idol look on its cover, Rolling Stone depicted Tate-LaBianca Murders mastermind Charles Manson as a serious visionary on the front page. Rather than a fruit loop, Manson, according to the first-name-basis (“Charlie”) Rolling Stone article, offered criticism of the legal system that was “obviously accurate in many ways” and was principled for refusing to plead insanity. If Rolling Stone‘s taste in music only recently went sour, its take on current events never quite got taken seriously, at least by serious people.

Remarkably, the New York Times, in its story on the sale, describes that disowned and discredited UVA Rape Case piece as an article about “an unproven gang rape.” And that, in four words, explains why people don’t read Rolling Stone or the New York Times like they used to.

At least the Times can boast of scooping Rolling Stone on its own obituary. And in that piece, the magazine’s publisher argues strenuously that Rolling Stone remains not only alive but thrives.

“Rolling Stone has played such a role in the history of our times, socially and politically and culturally,” majority stakeholder Wenner told the Times. “We want to retain that position.”

Yes, and Eastern Airlines wants to continue to dominate the New York-to-DC corridor, too. Rolling Stone playing a role in the history of our times is history from another’s times projected onto our times.

In this era, the magazine suffered a death by identity crisis long before it tethered its fortunes to a girl-who-cried-wolf article published because its editors refused to question stories that clashed with their narrative and narrow-mindedness. Like Don Cheadle’s Buck Swope in Boogie Nights, Rolling Stone’s permanent identity involves not projecting a permanent identity.

Is it a politics magazine? Covers in 2017 feature MSNBC talker Rachel Maddow, HBO host John Oliver, and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Is it a celebrity magazine? In the last year, actor Jared Leto with his shirt off, pop star Harry Styles practicing a pose for Tiger Beat, and Michael Jackson’s daughter wearing a Magnum/Blue Steel expression next to a “Paris Breaks Her Silence” (as though nobody listening means a disciplined muteness) caption all greeted readers at the newsstand. Is it a nostalgia publication for Baby Boomers? Bruce Springsteen, Chuck Berry, and The Rolling Stones (average age: 76) graced the cover in the last 12 months.

Along with MTV, Rolling Stone contributed to the demise of the music industry—something that once so defined young people that they named several of their various tribes (metal heads, goth kids, etc.) for genres—after it contributed to its growth. Along with MTV, it once served as a tastemaker in both music and the broader youth culture. It died by becoming a celebrity magazine, and one that periodically imagined the stars of 1972 as the stars of 2017. Its juvenile politics, perhaps charming when its readers—and a too-massive portion of the American public—looked like juveniles, aged poorly. Add to this the challenges facing any print periodical, and one sees how a niche publication with a broad readership became an all-accessible magazine with narrowing appeal.

When did Rolling Stone die?

When it morphed from newsprint to glossy? When it moved from San Francisco to New York? When it attempted to open up a chain of restaurants in imitation of the Hard Rock Café? When it put the stars of something called “Gossip Girl” on its front page both licking a two-scoop, ice-cream cone or made coverboys of the Backstreet Boys with their pants down to their ankles or posing Sarah Michelle Gellar with her legs akimbo on a Cadillac? When it shrank from oversized floppy magazine to standard, run-of-the-mill 8-by-10, in subconscious acknowledgement of its diminishing relevance, in 2008?

Maybe it died a thousand deaths, with a Charlottesville mob spray-painting graffiti on a fraternity house and shattering its windows with bricks putting an exclamation point on all those Rolling Stone ceased-to-exist moments. Rolling Stone’s eulogists can credibly claim that it never became Spin. They can’t say, at least for long, that it never became McCall’s, Harper’s Weekly, Life, Spy, or George.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.