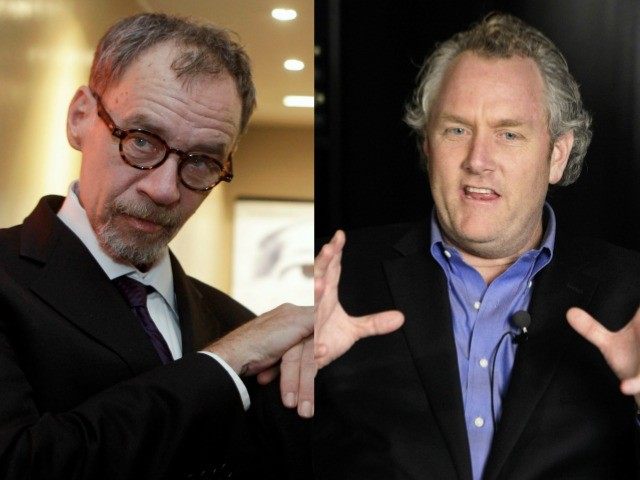

EDITOR’S NOTE: Shocking news in the media tonight: New York Times columnist David Carr collapsed in the newsroom on Thursday night and was later pronounced dead. He was 58.

Primarily a media and culture writer, Carr was one of the most established brands at the most established publication, yet he approached his topics earnestly and with markedly less cynicism than most of his mainstream media peers. A perfect illustration of that is the exceptional 2600-word profile, “The Provocateur,” he penned after the death of Andrew Breitbart. We’ve excerpted it below, but make sure to read the whole thing.

Carr, who struggled with drug addiction, interviewed Edward Snowden and Glenn Greenwald hours before his death.

Few writers have Carr’s gifts for language and storytelling, and fewer use those gifts without belittling either subject or reader. It’s tragic he won’t get to use those gifts any longer.

ANDREW BREITBART jacked into the Web early and never unplugged. As someone who worked on the Drudge Report and The Huffington Post in the early days and was busy building his own mini-empire of conservative opinion and infotainment at Breitbart.com, he understood in a fundamental way how discourse could be profoundly shaped by the pixels generated far outside the mainstream media he held in such low regard.

Mr. Breitbart, as much as anyone, turned the Web into an assault rifle, helping to bring down Acorn, a community organizing group, with the strategic release of undercover videos made by James O’Keefe, a conservative activist; forcing Shirley Sherrod, an Agriculture Department official, out of her job with a misleadingly edited clip of a speech; and flushing out Representive Anthony D. Weiner, Democrat of New York, when he tried to lie about lewd pictures he had sent via Twitter.

Less watchdog than pit bull (and one who, without the technology of the 21st century, might have been just one more angry man shouting from a street corner), Mr. Breitbart altered the rules of civil discourse.

Mark Feldstein, a journalism professor at the University of Maryland, said that Mr. Breitbart “used the tools of invective and polemic to change the conversation, to try to turn it to his advantage.”

Mr. Breitbart was a ubiquitous presence on and off the Web, though not one who ever managed to have significant business success there. His star rose along with the Tea Party, of which he was an early and frequent defender.

But he cut an odd figure for a conservative, holding forth with lectures on political theory that name-dropped Michel Foucault and other leftist thinkers. He could also be mordantly funny. (His Twitter avatar was an echo of the apocryphal Jesus imprint on a piece of toast.) Matt Labash, senior editor at The Weekly Standard, described him as “half right wing Yippie, half Andy Kaufman,” in his column after Mr. Breitbart died.

In 2011, while various religious groups boycotted the Conservative Political Action Conference because of the inclusion of gay Republican groups, he helped hold a party for the gay groups.

He was conversant in pop culture — the Cure and New Order were particular musical favorites — and thought nothing of wearing in-line skates, his longish hair trailing behind him, as he confronted protesters at a rally outside a conservative event hosted by David and Charles Koch in Palm Springs, Calif., in 2011. Once he was done berating the protesters, he took some of them to dinner at Applebee’s.

Read the rest of the article here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.