I don’t normally read “true crime” books, and I’ve certainly never written a review of one, but Errol Morris’ new book, “A Wilderness of Error,” isn’t typical of the genre. It’s much more interesting and I think important. It’s a book about the failings of a legal system administered by very fallible human beings, and it’s a book about how we buy into false media narratives that tidy up uncomfortably complex stories and give us permission to call off any further search for truth – and, yes, Morris argues with refreshing clarity that objective truth is real and worthy of being sought after despite the pretentious nonsense preached in faculty lounges about all truth being relative. In fact, he argues passionately that the search for truth is what journalism and justice is all about.

Morris describes how false narratives can become a sort of prison. He opens by reminding us of the story of “The Count of Monte Cristo” – the novel about an innocent man who escapes from the seemingly inescapable island prison he was sent to. Morris writes that today we have an even worse prison than that fictional one – only ours is “built out of newsprint and media. A prison of beliefs. You can escape from prison, but how do you escape from a convincing story? After enough repetitions, the facts come to serve the story and not the other way around. Like kudzu, suddenly the story is everywhere and impenetrable.”

Like a relentless gardener, Morris tries to remove the “impenetrable” vines forming one such prison. Most people of a certain age will recall the story of Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald. People remember him as the Green Beret doctor who killed his family and blamed it on hippies. That quick description also conveniently sums up the conventional narrative about him. The murders of his wife and two little daughters in 1970 at Fort Bragg were monstrous, and for the last three decades society has been content to know that MacDonald is serving three life sentences for the crime. But Morris asks his readers to consider something very upsetting: What if this man is innocent? How horrible is it to imagine a man first having to witness the brutal murder of his family and then being falsely convicted for it and spending over thirty years in prison?

Morris, an Academy Award winning documentary filmmaker whose past work was instrumental in freeing a man falsely convicted of murder, takes apart the key elements of the MacDonald case bit by bit. As the New York Times reviewer put it, “[Morris] will leave you 85 percent certain that Mr. MacDonald is innocent. He will leave you 100 percent certain he did not get a fair trial.” But how did we not hear about this sooner? The incompetent and corrupt manner in which this case was handled is outrageous. The errors are glaring. In order to comfortably be assured that MacDonald got a fair trial and is guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt” we have to forget a number of significant facts.

Forget the fact that a racist good old boy judge was openly contemptuous and hostile to MacDonald’s Jewish lead defense attorney and his opinion seeped into his decisions. Forget the fact that the prosecution withheld evidence and lab reports (and, according to new evidence, actually threatened the key defense witness to make her change her testimony). Forget the fact that the crime scene itself was badly mishandled – with evidence moved, destroyed, contaminated, and even stolen. Forget the fact that MacDonald had no motive for the crime, and that the in-laws who testified against his character had previously testified under oath praising his character. And most of all, forget the fact that MacDonald gave the police who arrived at the crime scene detailed descriptions of four suspects, and the police had spotted a woman who fit his description wandering around his neighborhood at 3 a.m. while they were on their way to the crime scene. Forget the fact that this same suspect also coincidentally confessed to multiple people that she and three men who fit MacDonald’s descriptions were involved in the murder of his family. Forget the fact that she was spotted that night with these three men by multiple witnesses – including by a witness who saw blood on her boots. Forget the fact that one of the men also confessed to the murders. Forget the fact that they even confessed to having a clear motive for wanting to commit the crime specifically against MacDonald and his family.

So, how was the public convinced that MacDonald was guilty despite all of these “reasonable doubts”?

Enter my old neighbor Joe McGinniss.

MacDonald signed a contract giving McGinniss exclusive rights to his life story, and so McGinniss was given unprecedented access to the defense team – living with them, working with them, eating with them. But when the guilty verdict came down, McGinniss did a one-eighty on them. Apparently, falsely convicted men don’t make for good books. McGinniss decided it was a better story to agree with the jury. MacDonald wasn’t a sympathetic figure. He did himself no favors with some media appearances. So, McGinniss went about writing a book that would convince people the government got the right verdict and we could all pat ourselves on the back and leave Jeffrey MacDonald to rot in his jail cell till Judgment Day.

McGinniss’ book actually embellished the prosecution’s case – even supplying a motive. According to McGinniss’ theory of the case, MacDonald secretly wanted to break free of his wife and kids and so he murdered them one night in a fit of rage induced by some diet pills he was taking. (Oddly enough, the millions of other people who were also taking those same diet pills somehow avoided murdering their families.)

Morris’ final description of McGinniss is apt: “a craven and sloppy journalist who confabulated, lied, and betrayed while ostensibly telling a story about a man who confabulated, lied, and betrayed.”

But perhaps the most disturbing passage in the book is when Morris considers just how McGinniss came by his theory of the case. Morris writes (and I hope I’ll be forgiven for quoting the whole passage):

McGinniss had claimed that MacDonald was “the kind of guy who could do it.” But who was McGinniss? Who was the guy who betrayed not only Jeffrey MacDonald, but the entire defense team? Not only did he live with them, eat with them, exercise with them– he worked with them, investigated with them, and worried with them. Or so it seemed.

There is a curious passage in Joe McGinniss’s book Heroes, which was published in 1976, long before he met Jeffrey MacDonald and began work on Fatal Vision. The passage was part of a diary kept by McGinniss and dated 1970. It starts in January of that year– just before the triple homicide in the MacDonald home– and chronicles McGinniss’s increasing fame, the end of his first marriage, and his affair with Nancy Doherty, who was to become his second wife.

Here are two brief quotes from the diary:

JANUARY My book was number one. Great to be young and a Yankee. I came to town to do the Cavett show and I threw a party in my suite at the Warwick. Six months earlier, I had lain in front of a television set with my wife, watching the Cavett show, and it had seemed another world, light-years away. She had said maybe someday you’ll be on it, and I had said oh, don’t be silly, and I’d meant it. Now I had done Cavett, Carson, Griffin, and all the rest. I had debated the House minority leader, Gerald Ford, on the David Frost show, and, quite clearly, he had come out second best.

MAY And warm mellow weekends. Nancy’s two teen-age sisters came to visit. And brought another girl along. The five of us swam naked in the river. We traveled a lot: to the Caribbean, to the Kentucky Derby, to speeches I was making around the country. Then we came back and gave a party. We opened up the whole house and gave a party for sixty people on the weekend of the Preakness. It was marvelous. I was Gatsby. And the rest of my life would be a party. Except that my wife called often on the phone. She pleaded with me to return. There were long, stuttering silences filled with sorrow. And my mother called, and my father, and pleaded, too. And my dreams were bad. I dreamed of going back to my wife and finding her old and horribly wrinkled. And I dreamed terrible dreams about the maiming and destruction of my daughters.

McGinniss wrote these diary entries nine years before the beginning of his partnership with Jeffrey MacDonald. The parallels between the biographies of Joe McGinniss and Jeffrey MacDonald are endlessly suggestive. McGinniss is writing about himself in these entries– not about Jeffrey MacDonald. And yet the outline of what McGinniss was to write about Jeffrey MacDonald nine years later was (in some nascent but clearly identifiable form) already there.

They were roughly the same age. McGinniss was born on December 9, 1942, MacDonald on October 12, 1943– less than a year apart. Both came from lower-middle-class families. Both were on the fast track. McGinniss in 1969 had published a bestseller, The Selling of the President 1968. MacDonald had gone to Princeton, received early admission to medical school at Northwestern, and became a Green Beret doctor with a promising career ahead of him. Both had married early and had been unfaithful to their wives. Both had two young daughters, and (at the time these diary pages were written) both of their wives were pregnant with a third child– a son.

But here’s a terrible irony. There is no evidence– despite McGinniss’s desperate efforts to find it– to suggest that Jeffrey MacDonald had “terrible dreams of the maiming and destruction of my daughters.” And there is evidence that Joe McGinniss did. He wrote about them in his diaries, and published them in 1976.

What are we to make of a man who projected onto a presumed murderer his own motives and impulses? But was MacDonald a murderer?

It is apparent to anyone who reads Morris’ book that MacDonald didn’t get a fair trial. But definitive proof of innocence may be impossible to establish now with the passage of so many years, with evidence lost and destroyed, and with so many key witnesses and potential suspects dead. If MacDonald is indeed guilty, then perhaps we should be more forgiving of McGinniss’ actions because despite his lies, he reached the right conclusion. But if MacDonald is innocent, which Morris’ book will leave you at least “85 percent certain of,” then what McGinniss did is disgraceful beyond measure.

Let me repeat that I don’t know with 100 percent certainty if MacDonald is innocent. I don’t know if he’s a monster who killed his family, or an innocent man tragically railroaded by the legal system. But I was sadly sympathetic to this letter he wrote to the author Janet Malcolm:

“…by altering the known facts, [McGinniss] has constructed an evil thing– his book– which unfortunately impacts many, many people as well as myself– all negatively– with the end result that a climate has been created that prevents any neutral airing of real facts. By lying for money, by selling an artificial view of reality, McGinniss has stolen from me, (or anyone) the ability to ever get the full truth out. Even assuming more truthful accounts of these eighteen years eventually are in the public domain, his work will always linger there, to poison the minds of many. How do you fight it…?”

The words of a murderer or an innocent man wrongfully convicted and then betrayed by a writer who lured the public into complacently accepting a false narrative? I don’t know with 100 percent certainty. But I do know from personal experience that McGinniss is a stone cold manipulative liar.

McGinniss shattered long-time relationships within my circle of friends and family with his horrendous actions while living 12 feet away from my kitchen and lying to people for his book about me and making them lie or twisting their words or even inventing “sources” out of whole cloth. The result of the “evil thing” he “constructed” was unjustly trashed reputations, shattered relationships, and a book of lies vomited into the public record.

What McGinniss did in my town and to my family was sick and vicious. I sympathize with MacDonald and his defense team because I saw firsthand the twisted way McGinniss operates. Before he moved in right next door to spy on us, he stalked us for months, making creepy unwelcomed “visits” to our house, as he tried to manipulatively win our trust the same way he won the trust of MacDonald and his defense team – all so that he could betray us just as he betrayed them.

Of course, I realize that what McGinniss did to thrash my reputation is nowhere near as horrible as what he did to corrupt the narrative of a murder case (especially if it helped keep an innocent man in jail), but it’s still egregious and disgusting because many in the media ran with it in order to add another chapter to their own false narrative. An “artificial view of reality” was sold to the public and no doubt many Americans were led to believe the garbage McGinniss wrote.

“How do you fight it?” I don’t know. But I recommend reading Morris’ book as a start and understanding for yourself what a character our former neighbor Joe McGinniss really is. If MacDonald is indeed innocent, I sincerely hope he receives justice. For what it’s worth, I am confident that with his track record of destructive lies, McGinniss will understand justice someday, in this life or the next.

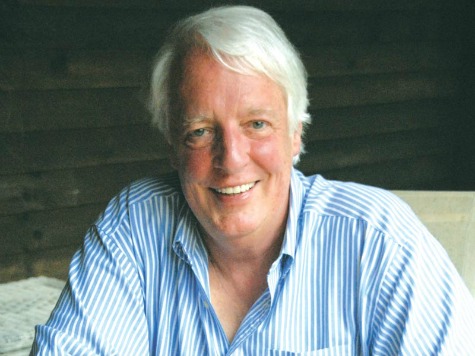

Headline image: Joe McGinniss portrait for Random House/photographer Nancy Doherty.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.