Three Options

The problems of Big Tech—including censorship, shadow banning, wokeness, monopoly power, and Chinese penetration—are, well, big.

So what to do? Broadly speaking, there are three possible strategies: first, accept the status quo; second, break up Big Tech through antitrust litigation; third, more regulation.

Let’s look at each strategy in turn:

The first strategy is accepting the status quo. Of course, that’s not much of a strategy, as it means accepting the rule of Big Tech owners—who include everyone from Mark Zuckerberg of Meta/Facebook (he of the Joe Biden-helping “Zuckbucks”) to Elon Musk (if his purchase of Twitter goes through). And yes, a few libertarians, not worried about life in the real world, have advised us to just let Big Tech do as it pleases. But let’s keep in mind: These are the same people who wanted Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) to ease up on Disney.

Without a doubt, Musk as a social-media owner is reassuring to most conservatives; as he declared in an April 25 tweet, “Free speech is the bedrock of a functioning democracy, and Twitter is the digital town square where matters vital to the future of humanity are debated.” Indeed, conservative accounts have already been gaining ground on the platform, even as Musk ascends into the conservative pantheon.

Yet it’s by no means a sure thing that Musk will pull off the Twitter deal; as we know, he’s been under ceaseless attack from the left, and it’s possible that woke capital could yet kibosh his bid. In fact, Musk has already accused big investors such as Bill Gates of shorting Tesla stock; that is, betting that the price will go down. If more shorting were to happen, Musk could possibly be deprived of the liquidity he needs to complete his purchase.

The Twitter profile of Elon Musk in shown on a cell phone on April 25, 2022, after it was announced that Twitter accepted Musk’s $44 billion bid to acquire the company. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Furthermore, we know that even the greatest hero won’t be around forever. And so it’s right and proper that Americans seek structural change, beyond any personality; last year The Wall Street Journal reported on a poll showing that 80 percent of Americans (83 percent of Democrats and 78 percent of Republicans) agreed that the federal government “needs to do everything it can to curb the influence of big tech companies that have grown too powerful.” So a change is gonna come.

The second strategy is antitrust litigation, which could potentially bust up Big Tech. In the last two years, 38 state attorneys general have joined an antitrust suit against Google, and 48 state AGs filed suit against Facebook. And when the Facebook suit was dismissed by a court (the AGs are appealing), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) stepped in and refiled it. At the same time, smaller antitrust suits are ongoing against Amazon and Apple.

In addition, according to Vox, Biden administration appointees at the FTC and Justice Department are aiming to do more: “They have Big Tech in their sights.” Vox adds, “We haven’t seen this kind of test of the tech sector since the United States sued Microsoft for antitrust violations in 1998.”

Uncle Sam’s suit against Microsoft was, indeed, a big deal, and yet interestingly enough, it still left Microsoft as a big deal; it is currently the second-most valuable company in America, boasting a market capitalization of some $2.17 trillion. The fact that MSFT has stayed so huge and yet attracts little controversy is a tribute to its management. The blue partisan coloration of its employees isn’t much different from the rest of Big Tech, and yet even so, the company itself hasn’t gone woke and censorious. And that’s a point to file away: It’s possible for a company to be big and well-behaved.

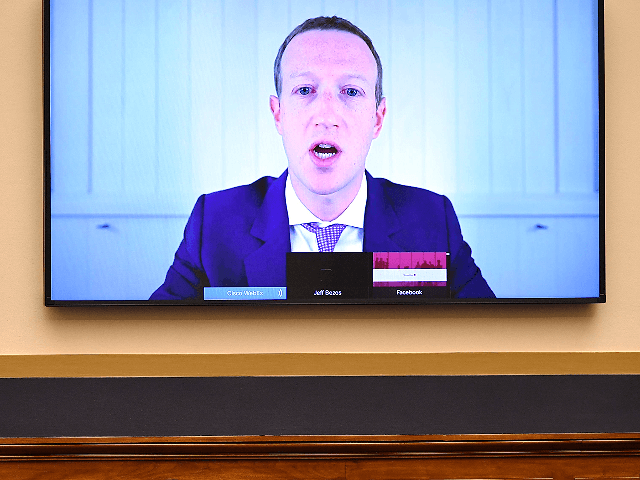

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law on “Online Platforms and Market Power” on July 29, 2020. (MANDEL NGAN/Getty Images)

One final point on antitrust as a strategy: If Facebook were somehow broken up, would any of the resulting pieces be automatically less woke and censorious? It’s possible that competition would drive some Little Facebooks to be less unfair, but it’s also possible that the Little Facebooks would simply collude with each other. So if we see a problem, maybe we should simply fix the problem and not dance around it.

The third approach is regulation. As we have seen, the public is emphatic for action, and it will eventually get what it wants. Yet along the way, we’re going to see—if we can bear to look—some legislative sausage being made.

The best-known proposal is the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, sponsored by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) In her words,

This bill prohibits certain large online platforms from engaging in specified acts, including giving preference to their own products on the platform, unfairly limiting the availability on the platform of competing products from another business, or discriminating in the application or enforcement of the platform’s terms of service among similarly situated users.

We can see: The bill has some antitrust-y elements to it, but it’s also a big dollop of regulation. As The Washington Post observes, “The bill…has become the epicenter of a massive power struggle between Washington and Silicon Valley.” The Post, of course, is owned by Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon—and so yeah, the Post itself is part of the epicenter. And as this author can attest, TV ads from the Computer and Communications Industry Association proclaiming, “Don’t Break Our Prime”—as in Amazon Prime—have been blanketing D.C. airwaves.

Klobuchar’s bill has gained 12 co-sponsors in the Senate, evenly split, Democrats and Republicans. Yet we might note that a co-sponsor is not necessarily the same thing as a firm supporter. It’s been known to happen that a co-sponsor signs on only to have “standing,” which is to say, the ability to stand next to the sausage at all times, as it wends its way through the meatpacking plant. In fact, one of the co-sponsors is Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA), a multimillionaire former tech executive, who says of the bill, “It needs some work, it’s not perfect by any means.” In other words, Warner is ready with his carving knife.

So prospects for Klobuchar’s legislation are uncertain; the Post says merely that the bill “may survive,” and Punchbowl News, an insider publication, adds that its passage is “a possibility.” For its part, Politico suggests that not much is going to happen on anything in the remaining eight months of the 117th Congress.

Yet after the 117th Congress comes the 118th Congress, in which Republicans might well find themselves having regained their majorities. And if so, Republican leaders will have to think about governing, as opposed to merely opposing. Yes, of course, partisan politics never goes away, but voters will be looking to leaders to actually solve pressing problems. And the biggest problem, always, is national security.

National Security Concerns and Big Tech

We might note that there’s a second Big Tech bill currently in play, namely, The Open App Markets Act, spearheaded by Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT). That bill would require app stores—such as those run by Apple and Google—to open themselves up to new competition. As with Klobuchar’s bill, this legislation, too, has met with strenuous opposition.

On April 18, seven former national security officials—from both parties, from both the legislative and executive branches—released an open letter in which they warned against tinkering with Big Tech:

Legislation from both the House and Senate requiring non-discriminatory access for all ‘business users’ (broadly defined to include foreign rivals) on U.S. digital platforms would provide an open door for foreign adversaries to gain access to the software and hardware of American technology companies. Unfettered access to software and hardware could result in major cyber threats, misinformation, access to data of U.S. persons, and intellectual property theft.

Critics pounced on the letter, calling it the handiwork of hired guns. Yet still, it’s simply true that we live in a world rife with hackers, spammers, spoofers and phishers, to say nothing of sophisticated enemy governments. And so it’s dangerous, and maybe even fatal, to dismiss national security concerns out of hand.

Furthermore, it takes knowhow and money to fend off these threats. So perhaps that argues for bigger, so that companies can afford to defend themselves—and us, their customers. The letter continues:

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marks the start of a new chapter in global history, one in which the ideals of democracy will be put to the test. The United States will need to rely on the power of its technology sector to ensure that the safety of its citizens and the narrative of events continues to be shaped by facts, not by foreign adversaries.

This nail of a point has been further hammered in omnipresent online advertising by a new tech group, the Chamber of Progress; it presents itself as sort of cuddly and liberal, but nevertheless it delivers a hard-edged hawkish national security message. For instance, it quotes Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) saying, “I’m concerned that this going to be very dangerous legislation.” Is Feinstein touting her Silicon Valley constituents? Is she articulating valid concerns? Maybe both? It’s important to take time to figure this out.

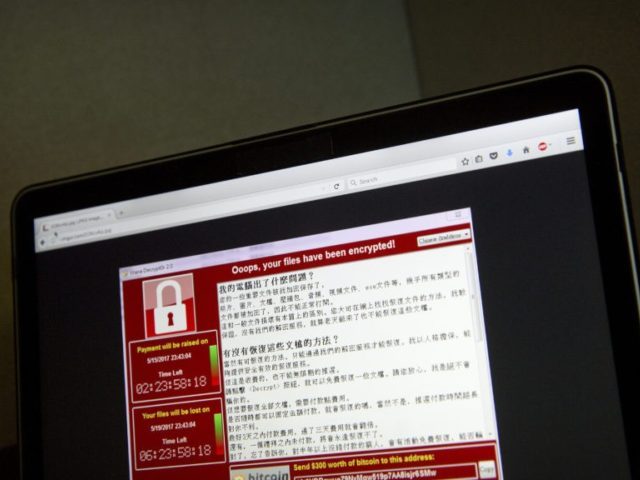

A screenshot of the warning screen from a purported ransomware attack is seen on laptop in Beijing on May 13, 2017. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

Moreover, the rise of cloud computing and the prospect of warfighting within the metaverse puts even more of a premium on secure computing. Back in February, War on the Rocks took a deep dive:

While a defense metaverse could enable a range of discrete warfighting and social benefits, its true value should emerge through the interconnection of the various defense virtual worlds — provided interoperability is prioritized in the design of these virtual environments from the start. Integrating virtual activities across the Department of Defense should create an iterative feedback loop, with little human effort involved, thus ensuring that lessons learned from training, education, or recruitment can be exploited during test and experimentation and vice versa.

The piece continued, “In some ways this mirrors the benefits that platforms—from Google to Amazon, YouTube, or Pinterest—provide.” A cynic will stop right there and exclaim, “That’s convenient for Big Tech!” And maybe it is. And yet maybe, too, it’s true. After all, the People’s Liberation Army is on the hunt in this same space.

So we should be informed by the stern warning from Breitbart News senior contributor Peter Schweizer in his 2022 book, Red-Handed: How American Elites Get Rich Helping China Win. Without a doubt, Schweizer makes Big Tech look bad, but then, he makes just about every sector of the American elite look bad–and proves his case. So the answer is to fix the problem by tightening up on China, and on American collusion with China. Pronto. And for that we will no doubt need a serious program of counter-intelligence, of the type we had in World War Two and the Cold War. Can we do that? Let’s hope. Because if we can’t, there’s no hope.

In the meantime, every patriot should at least listen to the arguments of the MIDC—Military Industrial Digital Complex. And then, as we shall see, improve upon them—to keep the whole country, and our individual rights, secure.

What Republicans Should Do

If Republicans win in 2022 and find themselves sharing power with President Joe Biden in 2023, they should be clear-eyed about Big Tech. Yes, we need Big Tech as part of our national defense, and yet Big Tech’s liberal tilt here at home is indefensible. So let’s get a plan to keep what we need and fix the rest.

Republicans should begin by clearing away the liberal fog on “disinformation,” The grim joke among Republicans is that Democrats wish to define anything they don’t like as either “disinformation” or “hate speech.” So if the GOP regains power, goodbye, Big Sister. With her and other Orwellian terrors out of the way, what else should Republicans do? How to move forward?

The GOP might take a tip from pro-Trump conservative activist Scott Presler, who argued in an April 25 tweet that no matter what happens with Musk and Twitter, “We must still legislate an Internet Bill of Rights,” which would declare “It is illegal & unconstitutional for social media companies to work w/ the White House to silence political opposition.”

There’s a key insight there: If you want to protect a right, write it into inviolable law. That’s the story of the First Amendment, and the Second Amendment, both of which (along with the other eight amendments that form the Bill of Rights) were important enough to be woven into the Constitution.

So we can now see the path ahead: We must lock in our gains. An Internet bill of Rights would thus include protections and due process on platforms, which should be legally deemed, as Sen. Hawley and others have suggested, to be common carriers.

Common carrier is a legal term, reaching back to Roman times, that requires certain public-facing facilities (roads, bridges, phone lines) to treat all customers equally. So now, let’s update that concept for the digital era, so that our digital rights, too, can be fully protected. Such rights could include protections for privacy, and against censorship and shadow banning.

So how to secure these rights? For that we will need some kind enforcement mechanism, that will probably end up being a sort of regulatory commission. To be sure, some on the right will blanch at the thought of a new government agency, but how else to protect ourselves? Since we can’t trust Big Tech—and since the Bible reminds us, “put not your faith in princes”—then we have to trust ourselves, all 332 million of us. It’s a simple point, really: Ordinary people can only find power if they organize, and that means creating an organization to serve as a watchdog for our rights.

As this author wrote back on January 24, 2021, “There’s an old joke: If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu. That is, if you aren’t a player in the process, you’re the one being played.” As I wrote further, “One possible answer is a Federal Platform Commission (FPC), overseeing Big Tech’s common-carrier responsibilities; and this FPC could be an outgrowth of the existing Federal Communications Commission (FCC).”

It’s worth noting that, by statute, the FCC must allocate at least two of its five commissioner slots to the Republican Party—and that’s two more seats at the table than the GOP has, at present, at any Big Tech company. Moreover, the entire FCC is all about due process and transparency; sure, it’s kludgy with bureaucrats and lobbyists, and yet at least the American people have a voice.

An FPC might not come all at once. It will likely emerge gradually, from the cumulative realization that Big Tech needs supervision—for the sake of our privacy, for the sake of the economy, and for the sake of our national security. And so a series of clarified benchmarks would, over time, morph into a structure: an FPC.

An FPC would not only protect our voice—making all tech companies are as well behaved as Microsoft—it would also be charged with thinking through the national security implications of Big Tech. That is, what policies we need to safeguard our personal data and our physical safety from all threats, including the danger of nefarious Big Tech cooperation with Beijing. So the FPC–as well as, of course, law enforcement-

Admittedly, the idea of an FPC is a big lift. And yet as we have seen, the problems of Big Tech are big. So while it’s great that Elon Musk seems poised to assume control of Twitter, it would be even greater if Americans could assume permanent control of their own digital liberties.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.