So Richard Branson beat Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk to be the first billionaire to go to space.

Much of the worldwide coverage of Branson’s space jaunt was bubbly enthusiasm. For instance, the Asia-based Wionews headlined, “Richard Branson realises his lifelong dream with Virgin Galactic spaceflight.” Indeed, critics tweet-pounced on coverage deemed fawning: “Almost everything that ‘CNN Innovation and Space Correspondent Rachel Crane’ is saying sounds like Virgin Galactic wrote it for her.”

To be sure, there was also criticism, including in this wordy headline from NBC News: “Richard Branson space flight beats out Jeff Bezos. But all of humanity loses. The stratification of who gets to leave the stratosphere is not another division we need.”

The Virgin Galactic SpaceShipTwo space plane Unity flies at Spaceport America, near Truth and Consequences, New Mexico, on July 11, 2021 before travel to the cosmos. Billionaire Richard Branson takes off on July 11, 2021 from a base in New Mexico aboard a Virgin Galactic vessel bound for the edge of space, a voyage he hopes will lift the nascent space tourism industry off the ground. (PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP via Getty Images)

Yet beyond the sheer bravura and ego-tripping of Branson’s flight, many news outlets addressed the larger idea of new people, including civilians, headed to space. For instance, the New York Times headlined, “Branson Completes Virgin Galactic Flight, Aiming to Open Up Space Tourism.”

In that vein, the tech site Ars Technica further advanced the private-tourism theme:

During the last 50 years, the vast majority of human flights into space—more than 95 percent—have been undertaken by government astronauts on government-designed and-funded vehicles. Starting with Branson and going forward, it seems likely that 95 percent of human spaceflights over the next half century, if not more, will take place on privately built vehicles by private citizens.

So in the future most people in space will be tourists? That’s a bold claim, and we’ll have to wait and see. Yet without a doubt, plenty of billionaires—way beyond Branson, Bezos, and Musk—have dreams of going to space and possibly of building a space station or of colonizing the Moon or Mars. And we should never sell short the ability of human drive and creativity to overcome even the most daunting challenges. (That point was well made in the first sci-story that the late great Arthur C. Clarke ever published back in 1945.)

However, we can say this much for sure today: those daunting challenges have not yet been overcome. And a good itemization of some of those challenges can be found in a tweet thread from Sim Kern, the spouse of a NASA flight controller.

Kern compared Branson’s brief trip to space to the protracted stays of astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS), currently orbiting the earth:

For a half-dozen people to exist up on the ISS it takes a ground team of thousands of people, constantly problem-solving how to keep them alive. Their quality of life is bouncing around in a narrow tube with the same 5 people who can’t really bathe for months . . . The only reason they’re alive up there at all is because multiple countries have thousands of brilliant, highly-trained engineers and doctors and astrophysicists and computer experts whose full-time job is keeping the astronauts alive and the ISS functioning.

Yes, it’s true. The ISS requires an enormous support infrastructure, dwarfing anything that Branson assembled at his space base in New Mexico.

And for his part, if Musk means it when he says that he wants to move permanently to Mars, that would likely first entail a Musk-sized—and then some—investment on earth.

SpaceX owner and Tesla CEO Elon Musk poses on the red carpet of the Axel Springer Award 2020 on December 1, 2020 in Berlin, Germany. (Hannibal Hanschke-Pool/Getty Images)

Now of course, it could be argued that innovative private-sector types will find ways to do things leaner and cheaper; so again, we’ll have to see what these ambitious space newbies come up with.

Kern continues, dwelling on the health hazards of space:

Every minute of their day is micromanaged so they can survive. They follow strict exercise regimens to keep their bones from turning to goo. They spend a ton of time studying systems and conducting repairs on equipment that’s continually breaking because SPACE WANTS TO KILL YOU.

It’s true. After months or more in space, astronauts come back in wheelchairs and stretchers. Indeed, a 2020 article in Nature lists the dangers of life in zero-g outer space or on low-g celestial bodies. Yes, it’s true that bones soften, and yet would be space-trekkers ought to factor in other hazards, including “cognitive decrements,” “space radiation health effects of cancer,” and “Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome.” With that last syndrome, one’s eyes bulge out to the point of potential blindness or brain damage.

Musk freely acknowledges these and other dangers. As he said earlier this year about his hoped-for Martian colony, “Honestly, a bunch of people will probably die in the beginning.”

Yet the prospect of people getting sick or dying in space raises some important questions. For openers, who will take care of those falling and fallen? Will there be advanced healthcare? Or disability insurance? Disability pensions? What happens to the deceased? And what happens to their survivors, to their property? And what about liability—financial, civil, or even criminal? And on and on.

Most likely, early eager-beaver volunteers for corporate space-missions will cheerfully sign away their rights—such as rights might exist anyway on, say, Mars. And yet over time, bureaucrats, lawyers, and law-enforcers will emerge. As all the needs and realities of humans on earth will start to manifest themselves in the new place, the demand for a proper legal framework will become overwhelming.

So, a few points to consider as we move spaceward:

First, as to the health dangers of space, great as they are, they probably aren’t greater than the dangers faced by ocean-going explorers of the 15th or 16th century. Most of those explorers died young, and yet those early deaths didn’t stop more from exploring.

Most likely, someone will figure out how to overcome the most serious health threats. There’s a lot of money riding on a solution, even if such a solution–such as somehow re-engineering humans–exists way-y-y outside of the familiar approval process of, for example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. And let’s also not forget that the space push is a multinational rivalry. Who dares guess what the People’s Republic of China will do to toughen up its astronauts? Moreover, as we know, the Chinese Communist Party imposes few, if any, limits on human medical experimentation. Another possibility is artificial gravity, as would be found, for example, in the highly hypothetical O’Neill cylinders favored by Jeff Bezos.

Second, the politics of space and space colonies will prove complicated. We’ve already touched on some of the potential legal issues, now to the political issues. Does the population of a space ship or a space colony have any political rights? Will there be elections?

Would space folks carry with them the privileges and immunities inherent in their citizenship in the “old country” or would, say, Musk on Mars have all-powerful dominion?

Speaking of dominion, can Musk claim all of Mars? Or just the patch of land that he settles on? And what if others, too—including Musk’s comrades and crew—want a piece of the Red Planet? How do they gain property and what can they do with it?

And here’s another one: If Musk means it when he says that he wants to use nuclear weapons to terraform Mars to create an Earth-like atmosphere, is everyone okay with that? And who will supply him with the nukes? Or do we let him just make them himself?

Third, the strategic politics of space are even more complicated. As of now, Branson and the rest are building their spacecraft with no defenses against attack. And why not? After all, today nobody is shooting at them.

But what if that changes? What if there’s even the hint that a hostile outfit of some kind (a country, gangsters, anarchist saboteurs) might have cruel intentions? This is a dangerous world, after all, because some people and some countries are greedy, graspy, and nasty. And whatever’s true on this world will soon enough be true in space, or on some other world.

So the billionaire space cadets will eventually have to think about defending themselves. One way to manage that defense would be build their own defenses. But alas, that would be hideously expensive and probably wouldn’t even work. Building a defensive shield is a lot harder than firing an offensive bullet.

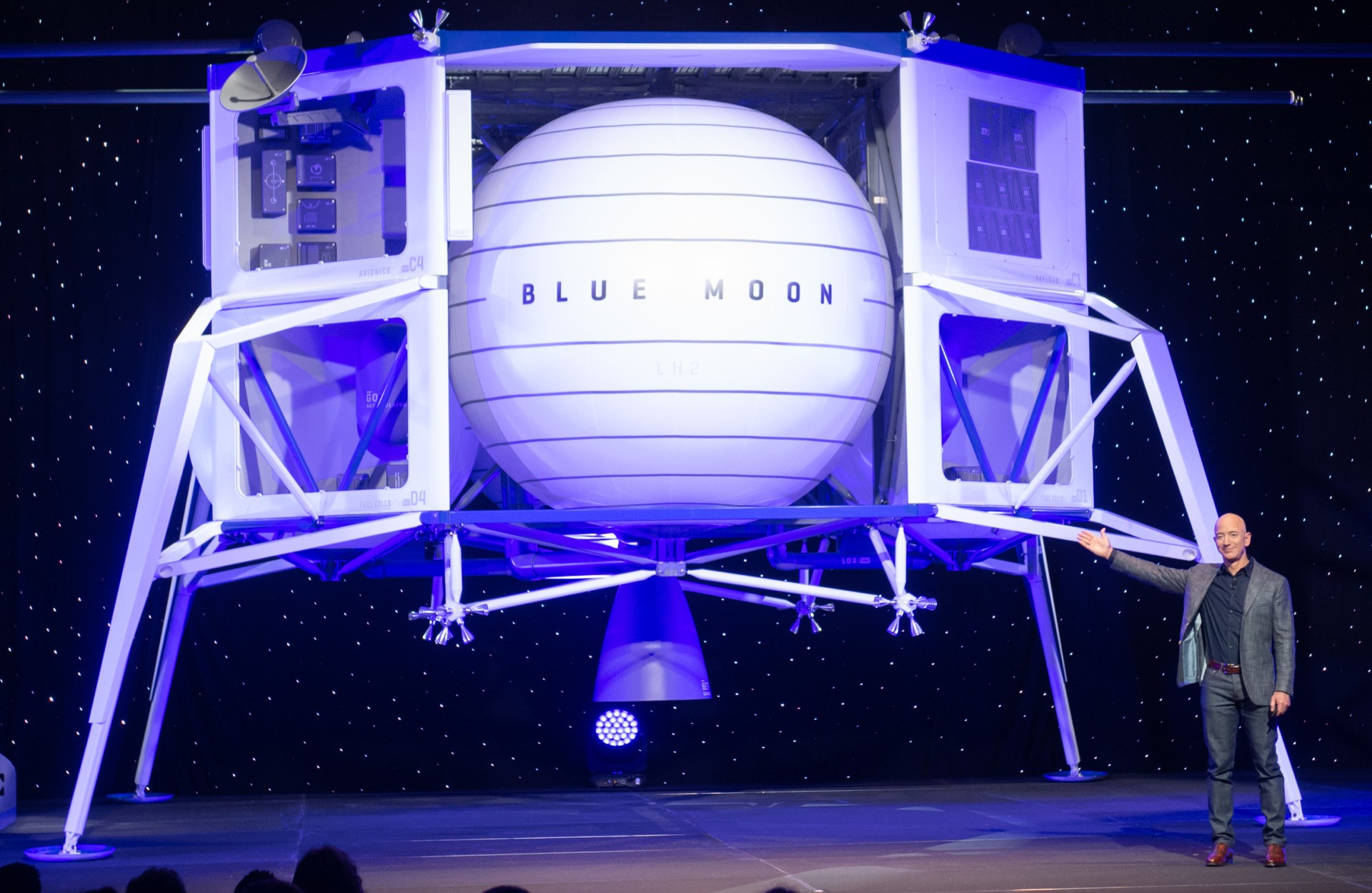

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announces Blue Moon, a lunar landing vehicle for the Moon, during a Blue Origin event in Washington, DC, May 9, 2019. (SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images)

Of course, another way to manage defense would be to get in league with an outfit that already has an existing strong defense. And one such “outfit” that meets that criteria is the United States, which boasts, of course, a strong military. Our military is strong enough to implicitly deter most attacks on U.S. citizens or assets, and it’s also strong enough to explicitly punish the attacks that do occur. Through those two mechanisms, deterrence and punishment, we stay safe.

In other words, the U.S. possesses exactly the sort of defense that Branson, Bezos, and Musk would need. They might ask themselves: Would they prefer to deal with China? With Russia?

So if the U.S. is the partner of choice, then the question arises: Is the U.S. inclined to defend private space travelers wherever they go? That is, if they go to space, does our defense, implicit and explicit, go with them?

That’s a question worth debating. After all, the citizens of this country, having had the embittering experience of two decades of endless war in the Middle East, might be a bit reluctant to take on an open-ended defense commitment in space. Yes, thanks to former president Trump, the Pentagon now boasts a Space Force, and yet as with any military asset, we should be judicious in its use. So the spaceniks will likely need to do some political persuading. How so? Well, they could, for example, promise to be better taxpaying citizens. And they could also be generous to American causes; which, interestingly enough, Bezos just did on July 14, giving $200 million to the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum.

Yet in addition, the spacers might make the argument that MAGA, Making America Great Again, also means MAGIS, or Making America Great In Space. After all, the history of America—even before the 19th century vision of Manifest Destiny–has been of expansion and greatness. And it makes perfect sense to keep that ambition going in the 21st century.

Yet for reasons that we have seen, if we do go to space in a big way, it will likely have to be as a public-private partnership. Yes, we benefit from private-sector creativity and incentives, but we also need the weight and might of Uncle Sam. Just as with the making of the United States, itself, if the U.S. government establishes a territory, it will be legally legitimate and politically permanent.

If the billionaires understand that dynamic and are willing to do their part for the nation and not just for themselves—and if American political leaders have the vision to see that going to space is a 1492-like opportunity—then this Branson moment could be the beginning of a beautiful partnership, a whole new epoch of American Greatness.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.