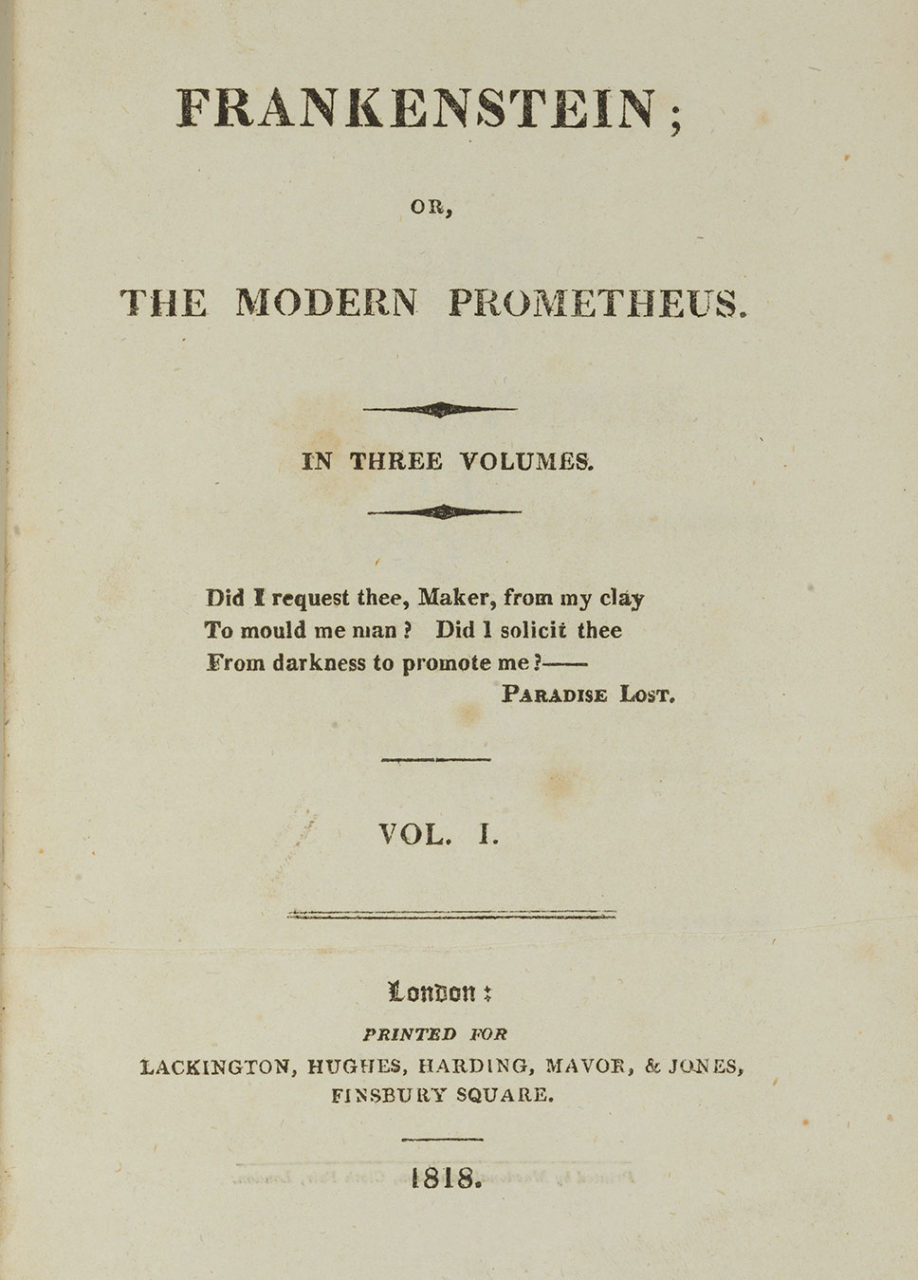

As he scans the news about tech abuses — from violating privacy, to manipulating the news, to mowing down pedestrians with driverless cars — Virgil is reminded that this year marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein.

This novel continues to stand as the greatest parable of scientific discovery run amok. And as such, it serves as a permanent reminder that the ambitions of human genius must always be tempered by the proper restraints of custom, law, and, of course, human decency.

Indeed, Frankenstein gets a shout-out in a new documentary, Do You Trust This Computer?, which highlights yet another potential tech danger, the rise of Artificial Intelligence, or AI. The film kicks off with a brooding quote from Shelley’s novel: “You are my creator, but I am your master.” And in the documentary, Elon Musk, the flamboyant tech entrepreneur, puts forth a bleak AI scenario:

We are rapidly headed toward digital super-intelligence that far exceeds any human … If one company or a small group of people manages to develop godlike digital super-intelligence, they could take over the world.

That’s scary enough, but Musk adds an even scarier point: “At least when there’s an evil dictator, that human is going to die. But for an AI there would be no death. It would live forever, and then you’d have an immortal dictator, from which we could never escape.”

Musk has been part of a group of sci-tech luminaries, including the late Stephen Hawking, who have been warning against AI for some time now. And yet most players in the AI world don’t agree with the critics. Instead, they say, AI offers greater economic productivity, greater scientific discovery — as well as, needless to say, greater profitability for AI-ers.

And as for larger public opinion, it’s fair to say that the issue simply hasn’t penetrated the political consciousness. Indeed, the reader might ask: When’s the last time a prominent politician ventured an opinion, pro or con, on AI? For better or worse, the political system is almost entirely oblivious to this surging technology.

In the meantime, AI is so powerful — some might say, so powerfully seductive — that it is rocketing along; already, AI is woven into much of the economy. In the words of one report, “Artificial Intelligence is not just a curiosity or a thought experiment, but technology that is spreading fast to businesses that average Americans interact with every day.”

Indeed, according to one study, 48 percent of large American companies are actively exploring AI, up from just 33 percent a year ago. And it’s been estimated that worldwide, in just two years, spending on AI will hit $46 billion. That much money will buy the speedy transformation of the planetary economy — as well as, perhaps, the military balance of power — and thus the lives of all of us.

So it seems evident: AI has so much momentum that there’s no stopping it. Will that onrushing lead to greater wealth and happiness? Or will it lead to a Musk-like doomsday scenario?

Today, even as we think about current trends to pick out clues to help us predict the future, bright or bleak, we might also look to a wonderful human resource. That is, to the cumulative history of our civilization, and to the lessons it offers us — if we’re willing to study and learn.

In particular, we might look back 200 years, to Frankenstein, because, with remarkable prescience, that novel laid out many of the issues that have both inspired and terrified us ever since.

The popular imagination of Frankenstein is indelibly stamped by a movie that came out more than a century after its publication. That was the 1931 Hollywood classic film starring Boris Karloff; it’s from that release that we get the “look” of the Frankenstein monster, as well as such flashy touches as the dark-and-stormy-night lightning strike that brings the creature to life. (In the novel, the process of giving life, while no less biologically profound, is less visually dramatic.)

And while the underlying plot of the movie is the same as that of the novel — the creation murderously defies its creator — the novel is, in many ways, more informative, because it deals more thoroughly with the downsides — and the upsides — of scientific advance.

For instance, the novel fully captures the romantic spirit of genius inquiry. In the rhapsodic words of fictional Victor Frankenstein, scientists of the early 19th century have learned so much that they can “ascend into the heavens … They have acquired new and almost unlimited powers; they can command the thunders of heaven, mimic the earthquake, and even mock the invisible world with its own shadows.” (We might pause to note that Frankenstein is the creator, not the creation; in fact, Frankenstein never gives his creation a name, although the creature calls itself, portentously, “Adam.”)

After his chronicling of others’ scientific achievement, Shelley’s Frankenstein explains that he himself is on a quest for “the elixir of life.” And he does so for a mix of reasons: First, he is compassionate toward his fellow humans, and second, he has an ego that needs to be slaked. As he declares, “What glory would attend the discovery if I could banish disease from the human frame and render man invulnerable to any but a violent death!”

So Frankenstein, increasingly obsessed with his self-appointed humanitarian work, spends years in “the dissecting room and the slaughter-house,” seeking to gain the body parts, and the knowhow, that he needs for his life-giving mission.

Then comes the moment of glorious epiphany, as the full radiance of scientific revelation dawns on him: “A sudden light broke in upon me — a light so brilliant and wondrous [that] I became dizzy with the immensity of the prospect which it illustrated.”

That prospect, of course, was the creation of life. As Frankenstein records, “No one can conceive the variety of feelings which bore me onwards, like a hurricane, in the first enthusiasm of success.”

Indeed, if we step back and think about everything that has been invented in the last two centuries, we can observe that the motivations of scientists are almost always, as Shelley suggests, a complicated human helix of impulses: on the one hand, a desire to help humanity, and on the other hand, a desire to aggrandize oneself. Both impulses, we can observe, can be sincere — even if they are somewhat contradictory.

In the novel, Frankenstein’s idealism ends disastrously; the monster proves to be, well, monstrous. And yet even as he is dying, mortally exhausted after his climactic duel with his creation, Frankenstein himself expresses the stubborn hope that future scientists will press ahead with their studies: “I have myself been blasted in these hopes, yet another may succeed.”

So there we have it: Frankenstein is a tragic parable of what can go wrong with scientific inquiry, and yet at the same time, it holds out hope that inquiry can be fruitful.

Obviously, the Frankenstein character is fiction. And yet unreal as he is, he has become real; the novel has given us the archetype of the “mad scientist,” and that’s a real type that we see every day in history and headlines. Thus the ultimate idea of the novel — that the human propensity to improve and advance must always be compared to the risk of unforeseen and unfortunate consequence — is borne out all the time, in real time.

Yet still, on the whole, science has been highly successful: the upside has vastly outweighed the downside. So while there have been plenty of mad scientists — and not all mad people are bad people — there have been plenty more scientists who were both sane and good. And we’ve all been the beneficiaries of their work.

For instance, in Frankenstein’s chosen field of medicine, the level of success has been miraculous; life expectancy has doubled since Shelley’s time. So yes, while some aspects of medical advancement give us the heebie-jeebies, it’s nevertheless hard to argue against a process that has given most people lives that are happier, more productive, and a good deal longer.

And the same rapid pace of advance, of course, has been seen in just about everything; it’s been estimated, for instance, that in the last two hundred years, since 1820, the U.S. standard of living has increased at least 2,500 percent.

Yet of course, just because we’ve had a great run in the last two centuries doesn’t mean that we will always have good running. History tells us that the twists of fate — and the far twister nature of human nature — may either vastly accelerate our progress, or send us crashing down.

And so back to the question of Artificial Intelligence. Is AI just another link of continuity in the long upward march of technology, akin to the periodic upgrades of, say, smart phones? Or is it a sharp discontinuity, hurtling us toward something we’ve never seen before — a Terminator-like future?

After all, if we’re now in the business of creating a new kind of thinking consciousness, it’s reasonable to ask: What will this new thinking consciousness think of us, the human race? Two centuries ago, Mary Shelley’s monster had its bitter answer, telling its creator, Frankenstein, “Man [mankind], you shall repent of the injuries you inflict.”

And now today, when so much science fiction has become science fact, it’s worth wondering if such silicon-based entities as Alexa, or Siri, or Nest — and more to the point, the algorithmic supercomputers backing them up — have an opinion about us carbon-based life-forms. Some people might scoff at the question of “opinion” when applied to a machine, and yet if the machine is smart enough to answer all of our questions, perhaps it might also be pondering, in its fashion, the basic questions of existence — its and ours.

So that leads to the final question: What should we think of the New Frankensteins? That is, the humans, worldwide, who are making all this happen — those scientific and technical explorers and venturers who are, “like a hurricane, in the first enthusiasm of success,” rushing us all toward a rendezvous with AI destiny. How should we regard them and their cyber-creations?

Virgil will take a look at some of these New Frankensteins in the next installment.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.