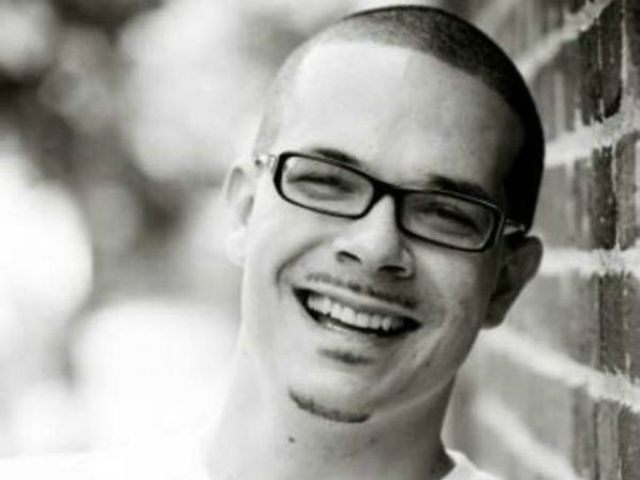

Victimhood is profitable. Nothing illustrates this better than the case of Shaun King, the disgraced Black Lives Matter icon.

King raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for causes ranging from assisting victims of the Haiti earthquake to a fund for the family of Tamir Rice, a 12-year old African-American boy who was shot by police in 2014 after his airsoft gun was taken to be real.

King set himself up as the champion of victims like Rice, marshalling his once-impressive social media army to pour money into good causes. But after a string of exposes about the murky status of these funds, King now finds himself evading questions from other leading figures in Black Lives Matter, including Deray Mckesson.

Much of the reporting on King’s murky history has been driven by Breitbart, where for months we have been asking the questions his supporters have avoided. Other outlets, such as the Washington Post, have also raised questions, but with nowhere near the same intensity.

Perhaps that’s why it took months for the seriousness of the allegations against King to dawn on Black Lives Matter. For movements built around left-wing identity politics, there are few things more painful than admitting Breitbart is right. But now that reality has dawned on Black Lives Matter, the question that will be on their mind is: who can we trust?

The first dilemma for the movement is that Shaun King is claiming blameless victimhood, while other leaders such as Deray Mckesson and Johnetta Elzie insist he has questions to answer. With the leadership of the movement at odds, factions are already forming.

But there’s a deeper question of trust that Black Lives Matter – and all movements based on the politics of victimhood – must grapple with. It is this: how can you separate genuine champions of the oppressed from those who take advantage of credulous empathy?

It’s a problem by no means confined to Black Lives Matter. The feminist vlogger Anita Sarkeesian rose to prominence on the back of a YouTube series about sexism in video games – a series whose fundraising campaign only gained traction after a swathe of media stories painted her as the helpless victim of internet trolls.

The case of Ahmed Mohamed, a 14-year old boy who rapidly became a darling of the media and political establishment earlier this year is another example. When news emerged that law enforcement had investigated him after his dissembled clock (a “science project,” according to Mohamed) was mistaken for a bomb, it created a spiral of outrage and virtue-signalling that included invitations to the White House from President Obama, an offer of a science scholarship at MIT, and a deluge of goodies from the tech industry’s household names.

News later emerged that Mohamed was a serial troublemaker who did not cooperate with the police, but by then the bandwagon had long since taken off.

These examples serve to illustrate a fundamental weakness in victimhood movements: when people are excessively empathetic, or outraged, or both, they become gullible. Pledges of support – monetary or otherwise – makes for good virtue signalling on social media, something that makes victimhood even more profitable in the digital age.

For Black Lives Matter, and, indeed for the whole of the victim-centric left, the question is not whether or not they can trust Shaun King. The question is whether they can trust any self-proclaimed public victim ever again.

Follow Allum Bokhari @LibertarianBlue on Twitter, and download Milo Alert! for Android to be kept up to date on his latest articles.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.