For those who have been following the decorated Metal Gear Solid franchise since its NES inception, you’ll feel a sense of homecoming when stepping into Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. But this is not the MGS of prior outings.

A series infamous for its extensive and elaborate scripted sequences has forsaken them almost entirely. Tightly orchestrated set-piece moments are mostly gone; in their place is a sandbox of emergent gameplay that frequently straddles the line between ludicrously cool and simply ludicrous.

My prior experience with the Metal Gear series has been relegated to brief attempts at each iteration of the franchise. I’ve played them all, but none more than halfway. I wanted to love each game. In theory, they tick just about all of my personal video game boxes: complex stories with tactical, stealth-focused gameplay immediately grab my interest, especially when they’re delivered with the gravelly ferocity of a 1980s action hero.

The problem has always been the manner in which these tales are told. From cutscenes surpassing the length of short films to meandering radio conversations between sparsely animated avatars, I’ve never felt as if I had any real impact on Snake’s exploits.

As the player, I was a side note. My entire purpose in a Metal Gear game has been a brief involvement with a few cursory button presses, briefly separating several hours of stilted philosophical debate between the increasingly far-fetched members of the cast. Like so many people, I’ve always assumed that Kojima really just wanted to make movies.

In this respect, MGSV is a marked departure. Most of the series’ DNA is restricted to the prologue. Within the first few moments of the game, you’ve already been exposed to flying children, pyrokinetic… somethings, and a whole lot of Kiefer Sutherland’s exposed digital ass.

Interactive entertainment has long embraced the ludicrous, and I’m not averse to wacky hijinks in my grimdark dystopias. What I find jarring, though, is the deadpan manner in which both dramatic and bizarre story elements are delivered, along with the endless but unexplained references to obscure elements of the franchise. It’s difficult to become immersed in a story that seems to be actively attempting to lose you.

By the time you are sent on your way — with a dramatic flourish and a musical crescendo – things are murkier than ever. Clarification can be found in a dozen or so audio logs accessible from your GPS, but that means another half hour of simply listening to exposition while you watch the familiar spin of a tape recorder. Holograms, robots, and yes: cassette tapes.

And it only gets weirder. Most of the comparatively thin narrative is contained within those audio logs. MGSV does very little storytelling within the world itself. Eavesdropping on guards occasionally foreshadows upcoming developments, but the conversations are brief and often repeated. If you really want to know what’s going on, you’re going to have to work for it. And by work, I mean listen to those tapes for a long, long time.

Despite all of this, I enjoyed my time with MGSV. Once the game is done floundering through its opening hours, the world spreads out wide before you. This is where MGSV comes into its own, and a patient player will be more than amply rewarded.

Gameplay revolves around the iDroid, your indispensable mobile hub. Its interface will guide you to and through your missions, provide GPS features, and organize both allied and enemy intelligence. Its design is as simple and streamlined as the popular devices it parodies, and it serves as the perfect in character means with which to navigate MGSV‘s broad slew of mechanics.

The iDroid’s primary function is mapping, and it does an admirable — if visually noisy — job. From it you can plan insertions and mark points of interest, shifting from simple height-mapping to something resembling monochromatic satellite photography. Once you’ve deployed, the area of operation is clearly delineated, reducing the wide wilderness to a mission-specific focal point.

The device will also provide your primary means of interacting with the aforementioned cassette tapes. More importantly, it will serve as your direct line to an organization that you will personally supervise as it’s reconstructed.

This organizational rebuilding is both your means to advance and your end goal. MGSV orbits the conceit of building a righteous private military corporation, the Diamond Dogs. To do so, you’re going to have to get your hands dirty. I’m not just referring to the forced recruitment through abduction of enemy soldiers: you’re going to need to pick a whole hell of a lot of flowers.

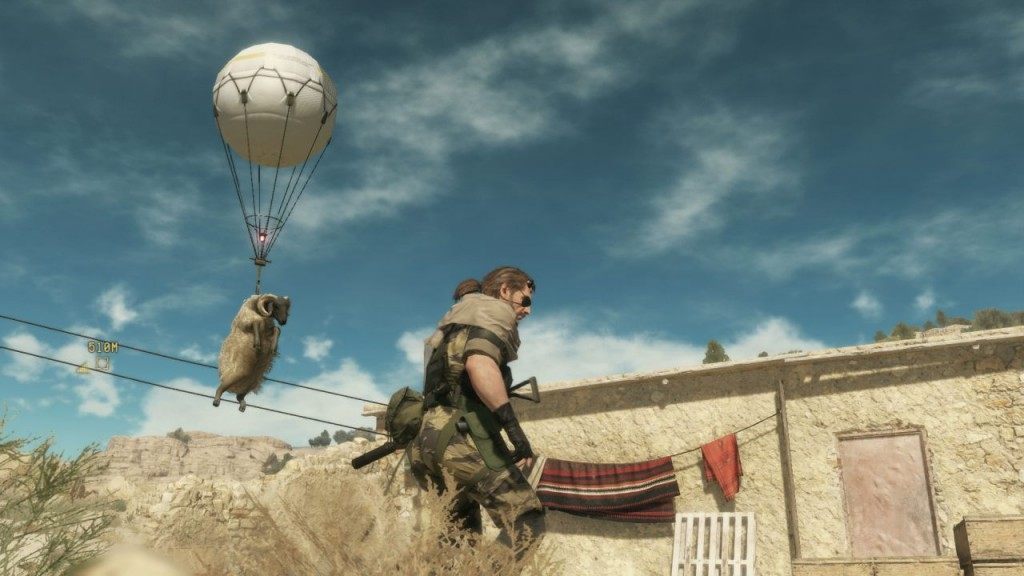

A typical slice of gameplay will see you approaching an enemy stronghold, then harvesting plants among the outskirts as you seek proper vantage of guard patrols. While the details of each operation change, the essential gameplay loop is always the same. You’ll observe, mark your targets where possible, and then either pick them slowly off from a distance, or creep close enough to send them literally screaming skyward on the tail of a high-speed balloon.

The “Fulton” balloon device is your primary means of acquiring new members of the Diamond Dogs. Unconscious men, animals, and equipment can all be attached to a small case that will then swiftly lift them for retrieval by your support team. Like the rest of the game, it’s just as smart as it is weird.

First of all, the Fulton adds tremendous incentive to conduct proper reconnaissance. Early in the game, your magi-technical binoculars can be upgraded with the ability to perceive an observed soldier’s skill levels. Enemy units with better skill sets are worth far more than their weight in GMP — MGSV‘s obligatory currency — and require special care not to kill them outright. If you can manage to incapacitate them, your Fulton balloon will send them off to meet what is presumably the most aggressive human resources department in history.

While this added focus on both recon and non-lethal neutralization of your enemies stresses a more tactical approach to each situation, the action itself still verges on the absurd. Whether you’re rescuing wild animals from a hot zone, saving a POW or abducting an especially knowledgeable guard for your own employment, each one leaps upward with a comical wail (or bleat).

In the midst of what is otherwise a game focused on tense moment-by-moment subterfuge, the slapstick extractions can be a real immersion-killer. I’d much preferred to have Snake simply tag them, and save the punchline for later.

Once the sheep and guards and prisoners in question have been liberated, it’s your job to manage them. You will assign soldiers to numerous departments in charge of developing weapons, equipment, and myriad support services for your use in the field. Even the expansion of your base itself is placed in your control, from the configuration of its defenses to the resources devoted to upgrading various branches.

If you’ve played a cell phone game in the last decade, you’ll be familiar with the Skinner Box approach to upgrades. Judicious use of timers ensures that you cannot progress too quickly, but for the most part they keep from being too obnoxious. It’s effective — for the most part, each upgrade feels both meaningful and distinct. Mother Base is a place you can actually wander, with its own challenges and diversionary encounters between missions in the field. You’ll refine weapons and equipment, but also the base itself.

The members of your staff are another key attraction to the meta-gameplay threads that run through MGSV. Each is a randomly-generated combination of names, skills, and faces constructed from a robust character generation system. You will encounter them in your periodic returns home, and they will grow and develop under your watchful eye. They may become wounded, sick, or be killed in action. They might even develop PTSD. Considering Diamond Dogs’ preferred hiring method, this seems inevitable.

While you will spend an ample amount of time ticking boxes and managing timers, all of it takes place off-screen. It’s almost impossible to develop any attachment to soldiers that are no more than a name on a list of hundreds, and the game wisely allows you to opt for auto-assignment areas which they are most suited.

Other than the occasional salute or canned “Good to see you, Boss!” your interaction with them is relegated to the number of men you’ve assigned to a project. After all the work that seems to have gone into making them each unique personas, the lack of interaction feels like a huge missed opportunity. Thankfully, the battlefield itself is replete with opportunities all its own.

The tools on the ground are many and varied. Your bionic arm is the most flexible of the lot, capable of functioning both as bait and a weapon in its own right. You’ll also have access to perhaps the most robust armory I’ve ever seen, along with tools that range from smoke bombs to inflatable decoys. Some are more useful than others, but all have a legitimate place in your loadout. You can stick to the methodical dissection of your objectives, but you can just as easily go in hot — guns blazing, walking away from explosions like a proper action hero.

After your heroics have ended, MGSV is liberal with its rewards. Efficiency is by far the highest standard of mission scoring, allowing each individual player to dictate their own methods of completion. It’s a good thing, too. MGSV doesn’t allow manual saving, and the checkpoints in most scenarios are sparse. Since save-scumming will punish you, improvising on the spot is a preferable option.

At every turn, Metal Gear Solid V exemplifies both the best and worst of the genre’s storytelling. Sometimes its tongue is planted firmly in its cheek, and other times it seems desperate for the player to take it seriously. The writing is stilted at best, and community-playhouse bad at worst.

The game’s moments of brilliance and abject stupidity combine to form an experience that can be as frustrating as it is exhilarating. The story itself drops steeply off at the end, but that seems an almost inevitable effect of the quarrels between developer Hideo Kojima and publisher Konami. For the faithful, the lack of a real ending might be infuriating. For someone less invested, it’s just flat.

Through all of these ups and downs, Metal Gear Solid V is still a great game. The controls are precise, the artificial intelligence is challenging, and the myriad ways in which you can approach a given scenario keep things fresh enough to sustain your interest.

It’s when the game tries too hard to be meaningful that it stumbles, and sacrifices compelling play for mawkish social and political commentary. Your own enjoyment will hinge on whether you find these idiosyncrasies endearing, but it’s still worth a purchase overall. Kojima’s swan song is, in the end, ‘a [very] Hideo Kojima game.’

Nate Church is @Get2Church on Twitter, and he can’t become a wildly overhyped internet celebrity without your help. Follow, then retweet and favorite everything he says. It’s the Right Thing To Do™!

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.