USA Today sports writer Dan Wolken speculates that if college football players launched political protests, they “just might” find that they have more “power” than they realize.

Even as he noted in his August 29 article that college teams do not take the field during the playing of the national anthem, and thus cannot use the anthem as a platform to push political crusades, Wolken wrote of his hopes that college players would find some way to protest.

The writer did point out that there are particular hurdles for protesting players in college ball. Among the larger problems, is that college players do not have a player’s union to back them up should they decide to protest.

Another roadblock to mass protests in college sports is the fact that fans have more direct impact in our colleges. While the NFL has TV money assured for years to come and might be able to better weather controversies, college sports have to be much more responsive to fans. If the fans don’t show up because of distasteful protests, or, donate to the various booster clubs. That financial fallout would hit the schools in the pocket book much faster than it might the NFL, Wolken points out.

“It speaks to the desire to control what the protest looks like and what the outcome is,” former pro player Wade Davis told Wolken. “They don’t want to lose money. They don’t want fans not going to games. I think it’s even more complicated in college than it is in the pro game because these kids have less power and it’s just a different dynamic in the NFL. These guys aren’t even paid, per se, in the same way, pro athletes are so there’s a different level of ownership the college level feels over their athletes. Imagine kids who play for Alabama kneeling. I mean, there would be a riot.”

Then there is the fact that college coaches have much more direct power over the lives of their players than NFL coaches do. In college sports the coach is king, and can do far more to punish a player than any NFL coach could.

Wolken notes that there have been discussions of possible protests throughout college sports. He quotes Virginia Tech’s athletics director Whit Babcock absurdly saying, “I was born in 1970, but it seems to feel a lot like the ’60s.”

Yet, Wolken thinks players might have power despite these drawbacks. The columnist pointed out the mass boycott perpetrated by players on the University of Missouri’s football team, that quickly toppled the school’s president. However, Wolken also notes that Missouri has never recovered from the controversy, considering that enrollment and donations have cratered since the boycott.

Regardless, Wolken hopes that college players find some way to protest.

“Given the current climate,” Wolken concluded, “it’s only a matter of time before someone tests that theory. And given how scared athletic departments are right now about this very scenario, even without an anthem to kneel for, college football players might find out they have more power and a louder voice than they ever knew.”

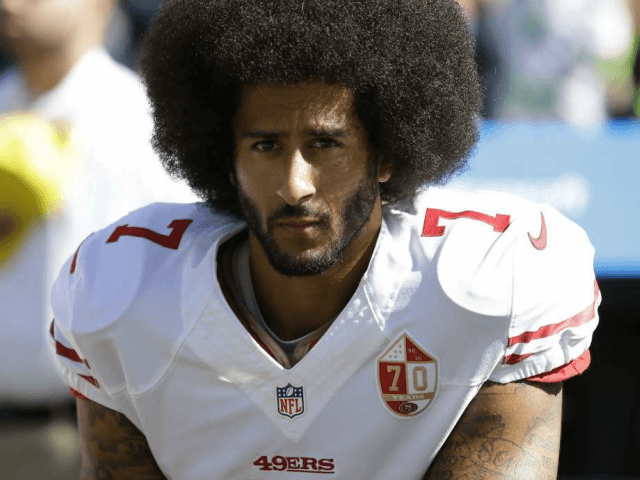

Finally, there is one consequence that Wolken does not seem to recognize: such protests just might become a sort of “rich man’s” battle. With most, if not all college players entertaining hopes of one day playing professional ball. Only the star players could stage political protests without incurring the risks of going undrafted. If a marginally talented player becomes better known for his exploits as a protester, than his skills as a football player, similarly to what’s happened with Colin Kaepernick. Then that player could find himself undrafted, and consequently, unemployed.

Just like Colin Kaepernick.

Follow Warner Todd Huston on Twitter @warnerthuston.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.