From the investigator touting as truth the opposite of the testimony of the AFC Championship Game referee on the matter most salient to Deflategate to the league admitting ignorance of the Ideal Gas Law to Roger Goodell hearing the appeal on the fairness of the suspension Roger Goodell handed down, the NFL gives its fans myriad reasons to doubt its investigation into Tom Brady.

Here are 25 of the ways in which the NFL railroaded the face of the league:

- Roger Goodell Called Ted Wells ‘Independent’—Until He Called Him His Lawyer

Roger Goodell repeatedly touted the independence of investigator Ted Wells. But when Tom Brady’s lawyers asked Wells questions about his “independent” investigation, he asserted attorney-client privilege a half-dozen times during the league appeal. Brady’s lawyer highlighted the conflict of interest. “Mr. Wells just testified he was independent and the NFL was not his client,” Jeffrey Kessler noted. “Therefore, Mr. [Jeff] Pash’s communications with him could not be privileged under any possible application of the privilege, unless Mr. Wells wants to change his testimony and state that the NFL was his client in this matter, which would mean he is not independent.”

- The NFL Does Not Know the Pregame Pressure of the Game Balls

The NFL bases its case on the assumption that all of the Colts balls measured at 13 psi and all the Patriots balls measured at 12.5 psi before the game despite referee Walt Anderson conceding on page 52 or the Wells Report some variation between the air pressure of each team’s pigskins. Wells accepts the uniform 13/12.5 measurements in part because of “the level of confidence Anderson expressed in his recollection”—but Anderson expressed no such confidence that all Patriots balls came in at 12.5 and all Colts balls measured at 13. In fact, the Wells Report concedes that “Anderson recalls that most of the Patriots footballs measured 12.5 psi” and that “most of the Colts balls measured 13.0 or 13.1 psi.” In other words, the Colts balls didn’t all come in at a standard 13.0 and the Patriots balls didn’t all reveal a uniform 12.5 pressure level, but for the sake of an argument let’s all just pretend that they did. We don’t know because the referees failed to document the pregame pressure levels.

- The NFL Disregarded the Testimony of the Referee of the AFC Championship Game

The Wells Report notes that according to referee Walt Anderson’s “best recollection” he utilized the gauge with a Wilson logo and “the long, crooked needle” to measure air pressure before the AFC Championship Game. Despite relying on Anderson’s “best recollection” elsewhere in the report, Wells dismisses it here. Relying on this gauge, according to Wells’s own scientists, clears eight of eleven Pats balls measured at halftime. So, incredibly, Wells decides to believe the opposite of what an NFL referee working in the league since 1996 told him, claiming in his report: “Walt Anderson most likely used the Non-Logo Gauge to inspect the game balls prior to the game.” By basing conclusions on the opposite of the testimony presented, one can prove just about anything—except the truth.

- Wells Used Amateurish Photographic Trickery

As pointed out in Robert Blecker’s amicus curiae brief for the appeal decided Monday, the Wells Report uses angles and photographic trickery to downplay the differences in the two needles used to gauge air pressure. The purpose appears more obvious than the differences between the two needles do in the pictures: Wells seeks to make his theory that Walt Anderson confused the two very distinct gauges more believable. Comically, the measurement starts well after zero on the picture with the shorter needle while on the picture of the longer needle the measurement starts at zero. Blecker also cites amateurish use of camera angles to make the needles look more similar in length. Based on this and other shenanigans, the New York Law School professor writes that “the NFL’s investigation, adjudication, and punishment of Tom Brady for actively participating in a scheme to illegally tamper with ball pressure has been infected with bias, unfairness, evident partiality and occasional fraud.”

- Wells Botched Basic Facts

The errors of fact in the Wells Report all curiously work to harm Brady’s case if believed. “Specifically, all but three of the Patriots footballs, as measured by both gauges, registered pressure levels lower than the range predicted by the Ideal Gas Law,” the report claims. This isn’t true, as the chart Wells highlights on page eight plainly shows. Eight of the balls measured by referee Dyrol Prioleau displayed readings at or above where Wells’s own scientists said balls inflated to 12.5 psi before the game would hit at halftime as a result of atmospheric conditions. Wells writes that “the Patriots balls should have measured between 11.52 and 11.32 psi at the end of the first half.” Ball 1 (11.80), Ball 3 (11.50), Ball 5 (11.45), Ball 6 (11.95), Ball 7 (12.30), Ball 8 (11.55), Ball 9 (11.35), and Ball 11 (11.35) all registered above 11.32 by Prioleau’s readings (Balls 1, 6, and 7 also did so by Blakeman’s). In other words, by Prioleau’s readings three balls gave readings above what Wells’s scientists predicted, three came in below, and five registered air pressure in the range the Ideal Gas Law predicted.

- Wells Wishes Away Wildly Fluctuating Gauge Readings

The halftime pressure readings fluctuate from game official to game official. Complicating matters, the readings don’t always show consistency for each official. Clete Blakeman’s readings uniformly run .3 to .45 psi lower on the Patriots balls than Dyrol Prioleau’s readings. Blakeman’s readings measure higher for the Colts, but on just three of four balls, than Prioleau’s. This suggests human error or defective equipment. This can’t stand if the Wells Report is to stand. So, once again, Ted Wells pulls out a sonic screwdriver to escape from an impossible situation. He claims that “it appears most likely that the two officials switched gauges in between measuring each team’s footballs.”

- The NFL Employs Circular Science Calibrating the Gauges

The NFL failed to locate the gauges used by the Colts and Patriots to inflate game balls. Given that the former team shot for 13 psi and the latter for 12.5 psi, the league figured that comparing the readings on the team gauges could help them determine which gauge Walt Anderson used before the game (despite the ref’s memory that he used the logo gauge). But the NFL says it couldn’t find the team gauges. To make up for this, they simply assumed the accuracy of the gauges used by the teams and obtained new gauges to calibrate the long-needled logo pump and the short-needled non-logo pump. “It turns out that all the other gauges they purchased then tested were the same model as the non-logo gauge, and none were the same model as the Logo gauge,” Robert Blecker writes in his amicus curiae brief. “They simply couldn’t locate any older Logo models the Wells report mentions in passing! Did they check Ebay? In any case this ‘investigatory’ bootstrapping is non-sequitur nonsense. Furthermore, as blogsters have pointed out the intercepted ball that began the whole affray, measured in the locker room 3 times with the Patriots’ gauge almost exactly matched the Logo gauge readings at halftime, thus clearly suggesting that the Ref, as he remembered had used the Logo gauge.”

- Wells Reading Between the Lines Always Benefits Incoming Thesis

Ted Wells interprets text messages between Patriots ball handlers that undermine his case as jokes and interprets texts messages between Patriots ball handlers that buttress his case as straight talk. When Jim McNally threatens to overinflate pigskins to the size of a “rugby ball,” a “watermelon,” or a “balloon,” he kids, the investigator posits, as he does when he promises, “The only thing deflating sun..is [Brady’s] passing rating.” But when McNally dubs himself, in the same chain of texts, the “deflator,” he writes earnestly about the true purpose of his employment with the Patriots even if in a “joking tone.” When McNally and John Jastremski call their texts jokes that Wells takes seriously, the investigator contends: “We do not view these explanations as plausible or consistent with common sense.”

- Wells Shielded NFL Correspondence by Citing Attorney-Client Privilege

The NFL investigation into Tom Brady lacked transparency because the investigator played two roles—disinterested information collector and interested NFL lawyer. Brady’s agent Don Yee outlined the frustration of making the case in the face of star-chamber proceedings in the league office: “[W]hen we requested documents from Wells, our request was rejected on the basis of privilege. We therefore had no idea as to what Wells found from other witnesses, nor did we know what those other witnesses said.”

- Wells Admitted an Employee Who Helped Write His ‘Independent’ Report Cross-Examined Brady

Lorin Resiner played the role of lead investigator during the “independent” investigation of Tom Brady. Then, in the appeal held at the league office, she suddenly became a partisan in the proceedings by cross-examining Brady. When asked if his Reisner had just cross-examined Brady, a dumbstruck Wells responded: “You saw it.” Asked if she had earlier served as a Deflategate investigator, Wells affirmed: “If you read the report, it basically says that.”

- Goodell Violated the Collective-Bargaining Agreement by Using Troy Vincent to Suspend Brady

When the NFL meted out the four-game suspension to Tom Brady in May 2015, they did so through Troy Vincent, which enabled Roger Goodell to hear the appeal, a role, to his regret, which he farmed out to his predecessor in the case of Bountygate. But this Kabuki Dance—seeing Goodell’s underling issuing the punishment and Goodell deciding on the fairness of that decision—didn’t jibe with the collective bargaining agreement, which called on Goodell, not Troy Vincent, to decide on punishment. So, Goodell changed tack.

- Goodell Heard the Appeal of His Own Decision

After the NFL Players Association complained that the collective-bargaining agreement did not authorize the NFL executive vice president of football operations to do the commissioner’s job, Goodell claimed that Vincent merely “communicated” the discipline “authorized” by him. Vincent used such language in his missive but given that he wrote the letter, and informed Brady, “If you wish to appeal this suspension, you may do so by sending written notice to me within three business days of this letter,” the public, and the players association, reasonably assumed he issued the punishment. Accepting the commissioner’s dubious rewrite meant that Goodell followed the collective-bargaining agreement by deciding the suspension. It also meant that the commissioner heard an appeal determining the fairness of a decision by the commissioner. So, the NFL either violated the agreed-upon rules by allowing Vincent to punish Brady or violated basic fairness by allowing the commissioner to hear the appeal of the commissioner’s ruling.

- Wells Created a False Impression That the Patriots Kept the Ball Handler from Follow-Up Interviews

Wells misleadingly charges that “the failure by the Patriots and its Counsel to produce [Jim] McNally for the requested follow-up interview violated the club’s obligations to cooperate with the investigation under the Policy on Integrity of the Game & Enforcement of League Rules and was inconsistent with public statements made by the Patriots pledging full cooperation with the investigation.” The Patriots made McNally available for three follow-up interviews with league investigators. They balked at a request for fifth interview. “I was offended by the comments made in the Wells Report in reference to not making an individual available for a follow-up interview,” Patriots owner Bob Kraft responded. “What the report fails to mention is that he had already been interviewed four times and we felt the fifth request for access was excessive for a part-time game day employee who has a full-time job with another employer.”

- The NFL’s Rules Specify a $25,000 Fine for Ball Tampering

The NFL stripped the New England Patriots of two draft picks, including a first rounder, fined the team $1 million, and suspended its quarterback for suspected ball tampering. When Fox’s cameras caught the Minnesota Vikings and Carolina Panthers heating balls at a freezing outdoor game in Minneapolis the very season the league suspects Brady and conspirators tampered with balls, NFL officiating guru Dean Blandino wrote the teams a letter telling them to stop messing with balls. That’s it—no $1 million fine, no suspended all-world quarterback, no stripped draft picks, and, in fact, no $25,000 fine.

- Goodell Bizarrely Likened Slightly Deflated Footballs to Steroids

In judging his initial judgment fair in the appeal, Goodell justified a four-game suspension because he deemed ball tampering on par with steroid use. “In terms of the appropriate level of discipline, the closest parallel of which I am aware is the collectively bargained discipline imposed for a first violation of the policy governing performance enhancing drugs,” the commissioner wrote, claiming “steroid use reflects an improper effort to secure a competitive advantage in, and threatens the integrity of, the game.” But as Judge Robert Katzmann noted in Monday’s dissent, stickum, not steroids, represents a more appropriate parallel. A first offense for the former rates a fine less than $9,000; for the latter, a four-game suspension. Katzmann recognizing “the Commissioner’s strained reliance on the penalty for violations of the League’s steroid policy” likely represents a point Brady’s lawyers stress on appeal.

- The NFL Changed Its Punishment Rationale When the Wells Report Fell Apart

Judge Robert Katzmann notes the commissioner’s “shifting rationale for Brady’s discipline” as a reason for his dissent from Monday’s ruling in favor of the NFL. Specifically, he points to Goodell morphing the “more probable than not” language of the Wells Report into unqualified judgments of definitive guilt in his verdict, and his reliance on a “conduct detrimental” catchall involving Tom Brady destroying an old cell phone. While calling the quarterback’s destruction of the cell phone terribly “ill advised,” Wells conceded that he received all the phone records he requested. Goodell’s shift from the alleged crime to the alleged coverup in part prompted Judge Katzmann to write: “I believe there are significant differences behind the limited findings in the Wells Report and the additional findings the Commissioner made for the first time in his written final decision.”

- The NFL Refused to Correct Its False Leaks

In the heady aftermath of the AFC Championship Game, influential ESPN pro football correspondent Chris Mortensen reported that 11 of the 12 balls Patriots balls measured two pounds or more under the league minimum. It turned out that just one ball did. The damning misinformation shaped public opinion for months. Reporters identified NFL director of football operations Mike Kensil as the source of the false leak. Kensil, whose father served as the president of the Jets and who worked for the Patriots’ rivals for almost two decades, taunted a Patriots ball handler during the AFC Championship Game: “We weighed the balls. You are in big f—— trouble.” Weighed the balls?

- Wells Employs Clear Double Standards

Wells states on page 70 of his report that “it is estimated that the footballs were inside the [referee] locker room for approximately 13 minutes and 30 seconds” at halftime. Sixty-three pages earlier, he states: “Only four Colts balls were tested because the officials were running out of time before the start of the second half.” Contrast this with his conspiracy theory that Jim McNally deflated a dozen balls in bathroom in 100 seconds. For Ted Wells, 810 provides a room-full of referees too small a window to measure all 12 Colts balls but 100 seconds gives the Pats employee more than enough time to deflate 12 balls. As it does elsewhere in the report, the logic shifts to give favor to his incoming hypothesis and throw shade on the case of his nemesis, Tom Brady.

- The Refs Botched the Measurements by Gauging Colts Balls Later

Ted Wells admits that the referees ran out of time to measure the pressure of all of the Colts balls after they measured all of the Patriots balls. This matters. Balls sitting in a warm locker room for a longer period of time will exhibit a smaller drop in pressure. The NFL did not know this. But a Nobel Prize-winning scientist does. “The smaller drop by 0.3 psi of the Colts balls can have a scientific explanation – they were measured at halftime after the 11 Patriots balls and thus had more time to warm up and increase pressure,” chemist Roderick MacKinnon writes. “Is it possible that the same Official could use one gauge for the Patriots and the other for the Colts measurements? Not only is this possible but it is exactly what happened at halftime.”

- Rivals Egged on the NFL to Conduct a Sting

Citing a tip by a Baltimore Ravens coach, Indianapolis Colts equipment manager Sean Sullivan emailed general manager Ryan Grigson prior to the AFC Championship Game: “It is well known around the league that after the Patriots gameballs are checked by the officials and brought out for game usage the ballboys for the Patriots will let out some air with a ball needle because their quarterback likes a smaller football so he can grip it better. It would be great if someone would be able to check the air in the game balls as the game goes on so they don’t get an illegal advantage.” Grigson petitioned the NFL to do just that, thanking them for “being vigilant stewards” of “the shield” and “the overall integrity of our game.” When the NFL found no malfeasance before the game, the Colts lodged another complaint before halftime.

- The Colts Balls Tested Also Lost Significant Air Pressure

Of the four Colts balls tested, all lost air pressure by halftime. On one of the referee’s gauges, three of four Colts balls lost so much pressure that they dipped below the minimum despite their purported inflation to 13 psi or more before the game. Wells curiously uses a double standard on Colts and Patriots balls. He writes that at halftime, “No air was added to the Colts balls tested because they each registered within the permissible inflation range on at least one of the two gauges used.” For the Patriots, he talks about balls not passing muster on “both gauges.” For the Colts, he employs a “one of the two gauges used” language, continuing the pattern of shifting the standard to suit his purpose.

- Wells Flip-Flops on Whether to Rely on the Referee’s ‘Best Recollection’

The Patriots seized on this inconsistency in their lengthy rebuttal. Referee Walt Anderson’s “recollection that he used the Logo gauge pre-game is the premise of the investigators’ justification for League officials not reinflating Colts footballs at halftime. But his recollection of which gauge he used pre-game is rejected when assessing the psi drop for the Patriots footballs. There is no rationale for this flip-flopping on whether Mr. Anderson’s recollections were correct.”

- The NFL Never Tested Drops in Air Pressure Prior to Deflategate

One of the reasons that drops in ball pressure led NFL officials to assume that it could only mean cheating pertained to the lack of precedent in re-testing balls at halftime or postgame. The NFL simply did not do this until Deflategate.

Jeff Kessler: Okay, so in all other NFL games generally, there is no testing at halftime at all, correct?

Troy Vincent: No, because we typically don’t have a breach with a game ball violation.

Jeff Kessler: Okay. And there is typically no testing after the end of the game regarding footballs, either, correct?

Troy Vincent: No, sir.

Jeff Kessler: So the only testing the NFL had in place was the testing before the game started as a routine matter.

Troy Vincent: Protocol, before the game.

- Roger Goodell Refuses to Release Results of 2015 Spot PSI Testing

Although the NFL retains no record of measuring air pressure at halftime or postgame prior to Deflategate, it possesses records of spot-checked balls after Defelategate. It just won’t let anybody examine them. Do they show that balls routinely lose pressure in cold-weather games? “We do spot checks to prevent and make sure the clubs understand that we’re watching these issues,” Roger Goodell told Rich Eisen in justifying the secrecy. “It wasn’t a research study.”

- The NFL Pleaded Ignorance on the Ideal Gas Law

The man initially meting out Tom Brady’s punishment admitted under oath that the league did not know that balls taken from warm locker rooms lose air pressure when moved to colder fields outdoors.

Jeff Kessler: Okay. So prior to this game, okay, had you ever heard of the Ideal Gas Law?

Troy Vincent: No, sir.

Jeff Kessler: Do you know if anyone in the NFL Game-Day Operations had ever discussed the impact of the Ideal Gas Law in testing footballs?

Troy Vincent: Not with me.

Jeff Kessler: You had never heard of that?

Troy Vincent: I hadn’t.

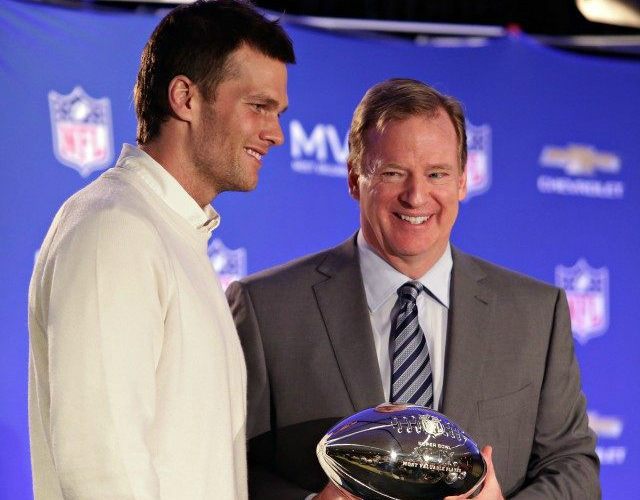

The Patriots defeated the Colts 45-7 in last season’s AFC Championship Game. The evidence shows a similarly lopsided victory over Ted Wells, Roger Goodell, and the NFL—even though an appeals court this week ruled that the league “met the minimum Legal standards” in their pursuit of the four-time Super Bowl winner.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.