Maybe Charles Barkley was right. Kids shouldn’t look up to athletes. They’re bound to let them down.

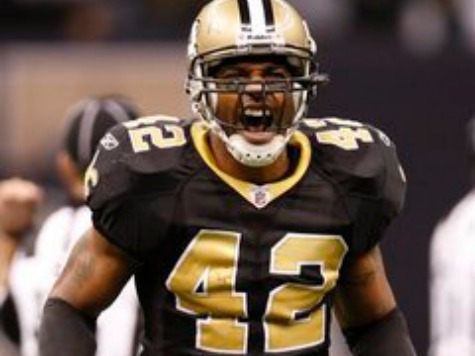

One of the latest heroes to fall is accused serial rapist Darren Sharper, a five-time Pro Bowler, Super Bowl champion, and, until his recent arrest, a talking head on the NFL Network. He’s also a co-author of NFL Dads Dedicated to Daughters, whose dust jacket announces that “domestic and sexual violence directed against women is a serious social problem that continues to plague America.” The book, a joint effort of the NFL Players Association and A Call to Men, addresses the crisis by enabling the “courageous men of the NFL,” like Sharper, to “share their thoughts and opinions on what it means to be a real man in today’s society while engaging in thoughtful discussions on the role men play in preventing domestic violence.”

“My daughter makes [me] mindful of how women are treated, undervalued and exploited,” Sharper wrote, “which is why I felt compelled to take advantage of this opportunity to speak up about domestic violence.” It’s on remainder for seventy-three cents a hardback on Amazon.

Sharper will have to pay a higher price–his bail increased to $1 million yesterday–for his continued freedom. In addition to Sharper’s arrest in Los Angeles based on allegations that he drugged several women with morphine and Ambien and then raped them, the former cornerback faces similar sexual assault investigations in Arizona, Louisiana, Nevada, and Florida. So far, nine women in five states not only accuse the same former NFL player of the same crime, they allege the same modus operandi, too. Sharper’s attorney theorized to a Los Angeles judge, “All of these were consensual contact between Mr. Sharper and women who wanted to be in his company, who voluntarily ingested alcohol and drugs in many cases.”

Darren Sharper didn’t need to look at his daughter to understand how women are “undervalued and exploited.”

The charges necessarily derail any momentum for Sharper–he ranks seventh all time in NFL interceptions–to be enshrined in Canton. They put him among more ignoble company in pro football’s Hypocrite Hall of Shame, an ever-expanding body whose standards remain considerably lower than Canton’s. Sharper, in fact, isn’t even the most recent inductee into the Pro Football Hypocrite Hall of Shame.

Ray Rice crusaded against bullies last year. “Anti-bullying is such a big deal,” the running back explained on the Baltimore Ravens website. “I started doing some research, and I was like, ‘This is crazy.’ It’s happening as we speak. I knew something had to be done.” Last weekend, police in Atlantic City charged him for assault on his fiancé. A surveillance video appears to show him dragging his unconscious girlfriend from an elevator. A security guard detained Rice. He knew something had to be done.

Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher earned a degree from the University of Maine in child development and family relations. Four years later, he murdered his girlfriend with their daughter in the next room before killing himself in front of his coaches.

In May, New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez received Pop Warner’s Inspiration to Youth Award. In June, police arrested him for murder.

Accused bully Richie Incognito, on his online reputation rehabilitation tour, tweeted of Michael Sam’s announcement of his homosexuality: “#respect bro. It takes guts to do what you did. I wish u nothing but the best.” But he allegedly hectored one Dolphins practice-squad player with anti-gay taunts last season and repeatedly associated behavior he disliked in Jonathan Martin with nasty names for homosexuals in text messages, e.g., “that’s the gayest s#!+ I’ve ever heard of. U really are a faggot.”

Incognito and his fellow Hall of Shamers highlight that there’s much that never makes the highlight reel. The acts of athletic-field heroism with which ESPN’s Sports Center bombards viewers represents a tiny fraction of the totality of player lives. Laying out one’s body in front of a linebacker to make a catch may make an athlete brave. It doesn’t make him a hero. Moral cowardice, unfortunately, sometimes accompanies physical courage. And given the millions of dollars at stake, NFL players will continue to say what we want to hear in public even when it conflicts with the way they behave in private. And visions of sack dances and touchdown catches will continue to blind fans to this grimy reality.

Somewhere around 2,000 players will cycle through the National Football League this season. Very few of them will receive speeding tickets, let alone indictments for murder, rape, and domestic violence. But the high-profile arrests of even a few players leave the league with a massive public-relations problem. Roger Goodell attempted to address such embarrassments in 2007 by instituting a personal-conduct policy, which empowers the league to punish players for off-field behavior.

Players suspended under the policy include the late Cincinnati Bengals receiver Chris Henry for arrests related to drugs, alcohol, guns, and underage girls; Adam “Pac Man” Jones, suspended twice through the Goodell rule; and Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger, the only player suspended based on mere allegations rather than convictions.

The Goodell rule may make malefactors think twice. But given that society imposes more stringent penalties on the activities alleged of Roethlisberger and Rice, the idea that it will turn bad boys into upstanding men seems dubious. Like the demonstrative shows of support for bullying victims and the league’s likely first openly-gay player, Goodell’s rule is more about public relations than anything else.

The NFL will continue to employ bad guys. Just about any collection of thousands of diverse individuals will contain Darren Sharpers and Aaron Hernandezes. But it will also contain guys like Russell Wilson. “God has given me the talent and opportunity to be an NFL player,” Wilson told ESPN. “I have a responsibility to God, my teammates, the fans to be the best I can be. I know kids look up to us. I view it as an opportunity, a platform.” Observing Wilson up close during Super Bowl week, I couldn’t help but notice that he walks a lot taller than his five-foot-eleven frame would indicate.

But one can’t help but notice that the knuckles of some of Wilson’s fellow NFLers drag lower than their arms suggest at first glance. Russell Wilson represents the average NFL player as much as Richie Incognito does. Imagining every NFL player as a Tim Tebow would be as naïve as imagining every NFL player as an Aaron Hernandez would be cynical. Whether spectators view NFL players through rose-colored glasses or jaundiced eyes, the fault for the distorted picture ultimately rests with the fans rather than the players. Stop putting on a pedestal 365 days a year that which merely rates a cheer on fall Sundays.

Fans might want to look at NFL stars with the words of an NBA Hall of Famer in mind. “I am not a role model,” Charles Barkley reminded in that famous Nike spot. “I am not paid to be a role model. I am paid to wreak havoc on the basketball court. Parents should be role models. Just because I dunk a basketball doesn’t mean I should raise your kids.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.