The supposed epidemic of NFL suicides joins acid rain, the Y2K bug, and the once imminent invasion of South American killer bees as a media narrative long on hype and short on evidence.

A Harvard Medical School researcher is the latest to explain that the link between football and suicide is greatly exaggerated. Grant Iverson, in a new article published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, also points out that speculation that chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the degenerative brain disease found in Junior Seau, John Mackey, Dave Duerson, and several dozen other deceased football players, increases the risk of suicide lacks scientific substantiation.

“Former NFL players were less likely to die by suicide than men in the general population,” the doctor working in Harvard Medical School’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation notes of a comprehensive 2012 study of NFL veterans by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). “There were only nine reported case[s] of suicide between 1960 and 2007. Therefore, according to the only published epidemiological data until now, NFL players are at decreased risk, not increased risk, for completed suicide relative to the general population.”

Put another way, saturation media coverage whenever one of thousands of NFL players commits suicide does not mean that thousands of NFL players commit suicide. In fact, the NIOSH study reported that the non-NFL peer group displayed a rate of suicide more than double the rate for the roughly 3,500 pension-vested NFL retirees studied. Just nine pension-vested NFL veterans took their own lives over a roughly five-decade period, with several committing suicide following the study’s completion.

Nevertheless, articles in the New York Times and other leading publications have falsely attributed inflated suicide rates to NFL players. A 2012 piece in the Christian Science Monitor, for instance, claimed that “the suicide rate of former NFL players is six times the national average, possibly due in part to a brain disorder that researchers say impacts those who have suffered multiple concussions.” Other publications peddling the false six-times-the-national-average statistic include the Chicago Sun Times, San Diego Union-Tribune, Washington Post, Bleacher Report, and Time.

It’s not just that so many articles in prominent newspapers and magazines repeated a statistic pulled from thin air. They ignored the actual science that contradicted their claims to do so. A piece containing the inflated NFL suicide numbers by Frank Bruni in the New York Times, for instance, came out more than six months after NIOSH released its findings.

Iverson points out that the assumption that linked CTE to suicide sprang from the initial cases of the disease discovered in football players, several of whom had died at their own hands. A few researchers, like many journalists, mistook correlation for causation. But as the number of brains studied grew, the percentage of suicide cases shrank.

For instance, Iverson notes that suicide caused the deaths of just three of the thirty-three NFL players examined in a recent journal article authored by researchers affiliated with Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. Among the non-NFL brains examined, the BU group reported ten suicides among the 53 decedents, with the majority of those suicide cases not demonstrating any signs of CTE. Of the minority of brains in which researchers did discover CTE among that group of ten non-NFL suicide cases, three exhibited just stage 1 or 2 CTE. In other words, most of the CTE cases didn’t kill themselves, most of the suicide cases didn’t have the disease, and most of the few who did exhibited a less advanced form of it.

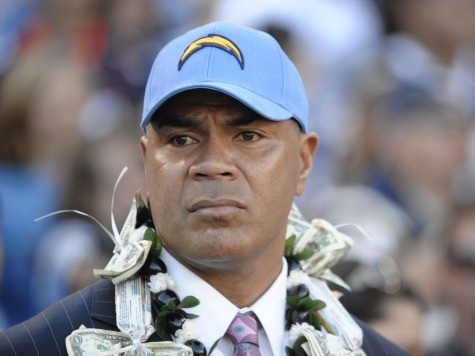

So, if not because of head trauma, why did these athletes kill themselves? The obvious answer is that people kill themselves for reasons unrelated to their professions or hobbies. Divorce, debts, declining health, and myriad other problems may encourage thoughts of suicide. Bears defensive back Dave Duerson experienced home foreclosure, bankruptcy, and the failure of a marriage. Broncos offensive lineman Mike Current faced thirty years in prison for allegedly molesting three children. Chargers linebacker Junior Seau drank five or six nights a week, gambled excessively, relied on various prescription drugs to sleep, and faced the imminent loss of his San Diego steakhouse. Football players generally kill themselves for the same reasons that salesmen, barbers, and nurses commit suicide.

Iverson’s article explores causal agents, independent of head trauma, for suicide that may be specific to athletes. These include prescription and performance enhancing drugs. For instance, Iverson cites a study of Swedish athletes that showed a link between past steroid use and suicide among power lifters, wrestlers, and other competitors. Might these same factors induce some NFL players to experience depression and commit suicide?

Elsewhere, the Harvard Medical School professor notes the frequency of suicides among major league baseball players: “Suicide is a societal problem–a problem that affects athletes in non-contact sports, such as cricket, baseball, power lifting, and track and field throwing events.” Iverson points out that Major League Baseball generally experiences a player or retiree suicide every other year, an observation consistent with my research in The War on Football: Saving America’s Game finding that over the last quarter century major-league ball players have killed themselves at a higher clip than NFL players.

“Finding evidence of the neuropathology of CTE in the brains of former athletes who complete suicide is a provocative but not statistically compelling source of evidence,” Iverson concludes. “The putative causal link in individual cases represents circular reasoning (ie, petitio principii).”

Daniel J. Flynn, the author of The War on Football: Saving America’s Game (Regnery, 2013), edits Breitbart Sports. Check back here tomorrow for part two of “The NFL Suicide Epidemic Myth” series.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.