WASHINGTON, DC — Racial preferences in college admissions violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution, the Supreme Court decided Thursday in a historic decision with profound implications for racial preferences in many areas of law and public policy.

The Supreme Court upheld racial preferences — euphemistically called “affirmative action” — in college admissions in the Bakke decision in 1978. Since then, debates have raged about whether to use quotas, point systems, or other ways of favoring one applicant over another based on the color of their skin, with the Supreme Court upholding some approaches while trimming the sails on others. Conservatives have insisted for half a century that the Constitution does not allow any of those approaches.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment commands that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The Supreme Court has always acknowledged that the central promise of the Equal Protection Clause is to forbid laws and public policies that discriminate on the basis of race.

While the Fourteenth Amendment applies only to state governments — which includes state and local public universities — Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 also extends racial discrimination to institutions that accept federal tax money, such as in grants and tuition aid. That applies to almost every private university.

Students For Fair Admission filed a number of lawsuits against public and private schools. The Supreme Court eventually took two of them: a challenge to the admissions policy of the University of North Carolina (UNC) under the Fourteenth Amendment and a challenge to Harvard’s policy under Title VI.

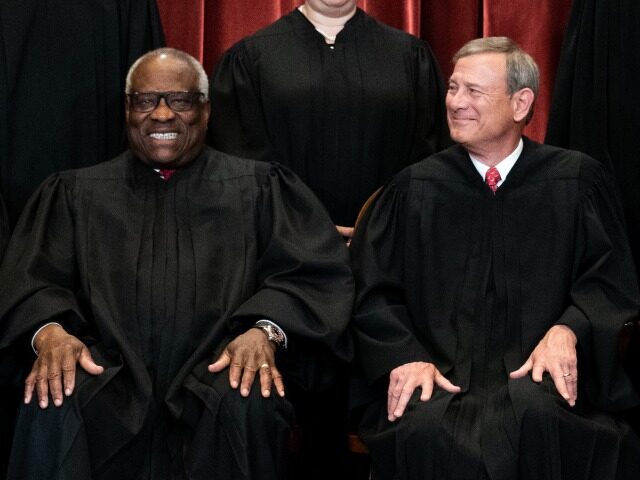

The Supreme Court held 6-3 that UNC’s policy is unconstitutional and held the same regarding Harvard’s policy by a 6-2 vote. (Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson recused herself from the Harvard case.) Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion, joined by all the conservative and moderate justices.

The majority opinion declared that “the Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause.” It concludes:

The Constitution deals with substance, not shadows, and the prohibition against racial discrimination is levelled at the thing, not the name. A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination. Or a benefit to a student whose heritage or culture motivated him or her to assume a leadership role or attain a particular goal must be tied to that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university. In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual – not on the basis of race.

Many universities have for far too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.

Justice Clarence Thomas joined Roberts’ opinion in full but also wrote separately to highlight the constitutional principle at stake:

In the wake of the Civil War, the country focused its attention on restoring the Union and establishing the legal status of newly freed slaves. The Constitution was amended to abolish slavery and proclaim that all persons born in the United States are citizens, entitled to the privileges or immunities of citizenship and the equal protection of the laws. Because of the second founding, our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.

The cases are Students for Fair Admissions v. Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, Nos. 20-1199 and 21-707 in the Supreme Court of the United States.

Breitbart News senior legal contributor Ken Klukowski is a lawyer who served in the White House and Justice Department.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.