On April 18, 1864, author Herman Melville rode through the twilight, embedded with the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry, on a scouting mission deep in enemy territory.

Nearly thirteen years had passed since the forty-four-old Melville had published Moby Dick, a book that was not considered a critical or commercial success during the author’s lifetime. Before the Civil War, Melville tried his hand at poetry and submitted a book of verse to his publisher. The manuscript had been rejected months earlier. To resurrect his career and eke out a living as a writer, he thrust himself into the war as a civilian and observer, capturing the conflict with his pen in a book of poetry titled Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War.

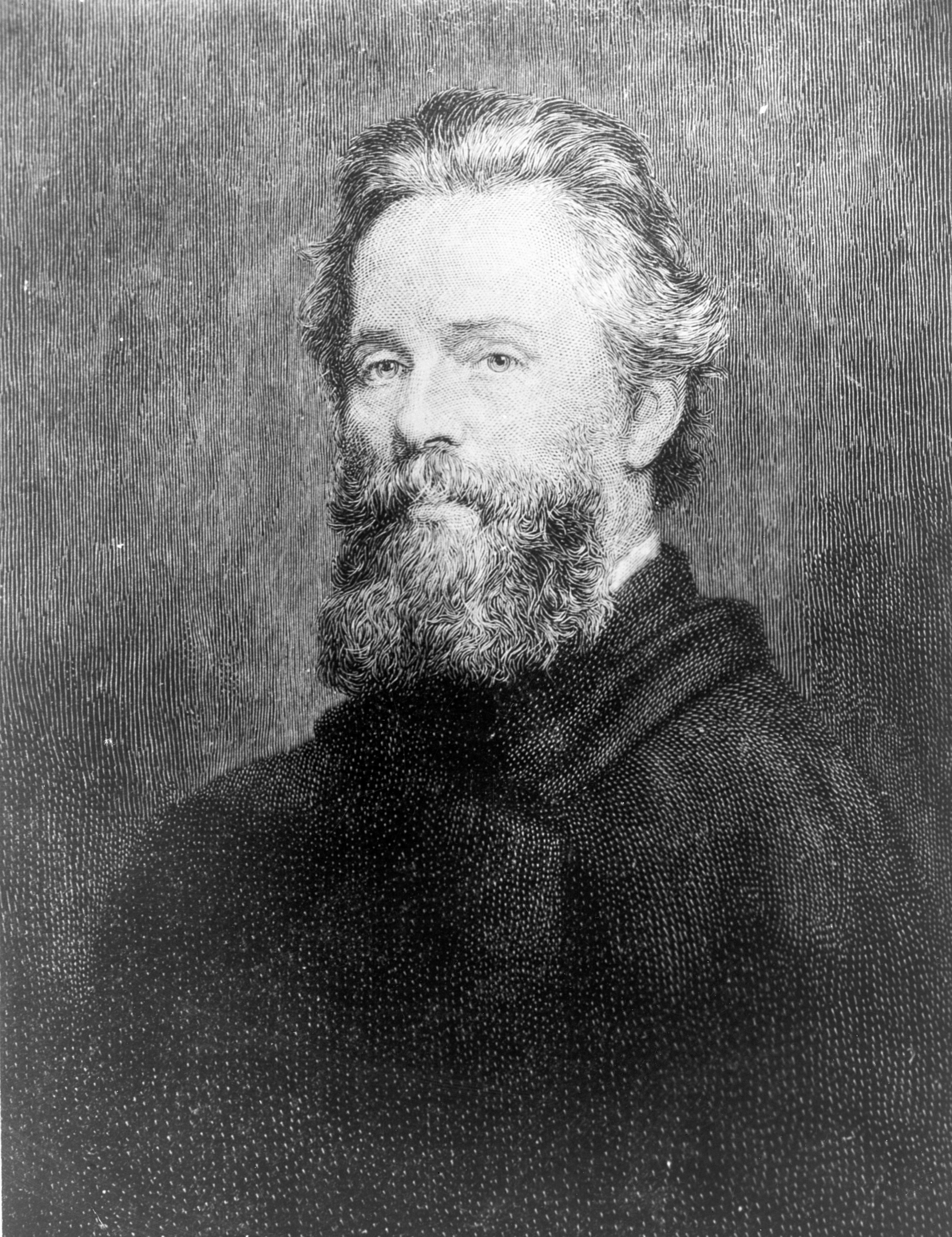

Herman Melville, (American author), head-and-shoulders portrait, facing left. Circa 1944. Photograph of an etching of Melville after a portrait by Joseph O. Eaton. (Photo by: Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The Union cavalry hunted Confederate guerrilla leader John Singleton Mosby and his intrepid Rangers, “the South’s most dangerous men.” These highly disciplined men, who never numbered more than a few hundred, terrorized the North—tied down tens of thousands of Federal troops, cut Union supply lines, captured generals, and pioneered a form of warfare that, had the South adopted it on a larger scale, would have prolonged the Civil War and perhaps resulted in a different outcome.

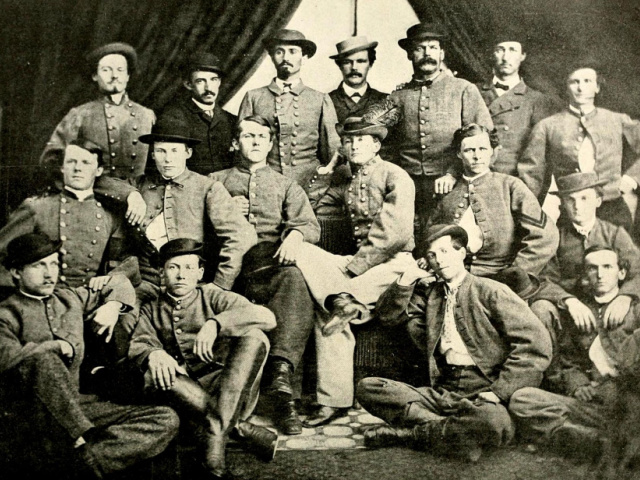

Mosby’s Rangers. Top row (left to right): Lee Herverson, Ben Palmer, John Puryear, Tom Booker, Norman Randolph, Frank Raham.# Second row: Robert Blanks Parrott, John Troop, John W. Munson, John S. Mosby, Newell, Neely, Quarles.# Third row: Walter Gosden, Harry T. Sinnott, Butler, Gentry, Public Domain

Weeks earlier in 1864, Mosby had launched a devastating ambush on the Union cavalry at Anker’s blacksmith shop about two miles from Dranesville, Virginia. Hiding in a pine thicket, Mosby relayed his orders: “Men, the Yankees are coming, and it is very likely we will have a hard fight. When you are ordered to charge, I want you to go right through them. Reserve your fire until you get close enough to see clearly what you are shooting at, and then let every shot tell.”

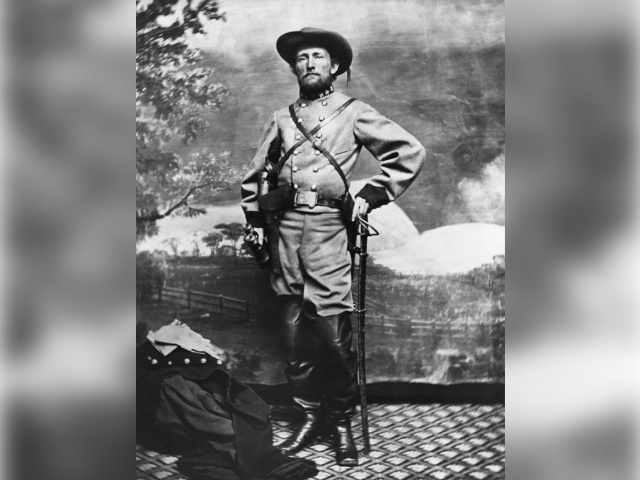

John Singleton Mosby stands in military uniform against a painted landscape. Mosby (1833-1916), an American colonel of the Civil War, was also an attorney and the United States consul to Hong Kong in 1878. (Photo by © CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Tension gripped the Rangers as the Union troopers approached. “We sat motionless on our horses, holding our breaths, with heads thrown forward and our ears strained, watching and waiting in anxious expectation for the approach of the enemy and the signal for the attack,” remembered Ranger James Williamson. An eerie silence and stillness enveloped the pine grove. The shrill shriek of Mosby’s whistle pierced the air.

The Rangers obtained the bulge and ran through the stunned 150-trooper patrol from the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry and the 16th New York Cavalry. In total, the Rangers lost one man but killed over a dozen Federals and captured over fifty more and scores of their horses.

Adapting from the loss of his men during the ambush at Anker’s, Massachusetts colonel Charles Russell Lowell determined to go after Mosby again with a larger force: 250 infantry and 250 troopers. Lowell, a scion from Boston, Harvard graduate, and industrialist, was Melville’s nephew and had recently married Josephine “Effy” Shaw, the sister of Robert Gould Shaw, who had famously led the 54th Massachusetts, America’s first all-Black regiment raised in the North during the Civil War.

The 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry was not a typical Northern regiment. The leadership of the 2nd Massachusetts were Californians, including the “California One Hundred” and the California battalion—volunteers so eager to join the fight that they had used their enlistment bonuses to purchase their passage via ship to the East Coast.

Lowell invited Melville to join the Massachusetts-California conglomeration on what the writer would immortalize as The Scout toward Aldie. The slow-moving force cautiously entered “Mosby’s Confederacy” even though Washington, DC, loomed in the distance. Rangers seemed behind every tree.

Melville’s elegant stanza captured the mood:

As glides in seas the shark,

Rides Mosby through green dark.

All spake of him, but few had seen

Except the maimed ones or the low;

Yet rumor made him every thing—

A farmer—woodman—refugee—

The man who crossed the field but now;

A spell about his life did cling—

Who to the ground shall Mosby bring?

The full story of Mosby and the men who hunted him is told in my new bestselling book, which makes an excellent Father’s Day present: The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations. The book reveals the drama of irregular guerrilla warfare that altered the course of the Civil War, including the story of Lincoln’s special forces who donned Confederate gray to hunt Mosby and his Confederate Rangers from 1863 to the war’s end at Appomattox—a previously untold story that inspired the creation of U.S. modern special operations in World War II as well as the story of the Confederate Secret Service. The book gives a ground-breaking fresh perspective on the Civil War.

As Lowell’s men left their camp near Centreville and rode toward Aldie, Mosby’s men took potshots at the column but wisely avoided a direct engagement with the Union commander’s superior numbers. The first day of the mission was a bust. As bugles sounded “boots and saddles,” the 2nd Massachusetts and other troopers beat the bushes only to find that the Rangers had vanished in the mist. One step ahead, Mosby’s men continued to slip in and out of the darkness beyond the Federals’ grasp.

Mosby used psychological warfare and played on the fears of all those who entered his realm, which Melville described in verse:

An outpost in the perilous wilds

Which ever are lone and still;

But Mosby’s men are there—

Of Mosby best beware.

The frustration and futility of war are captured in Melville’s account of the raid, as the Federals chased ghosts and were haunted by their own fears. On the second day of the mission, Lowell received a tip that the Rangers planned to attend a wedding in Leesburg that evening. Lowell divided his force and boldly sent part of it on foot to the town. The men arrived shortly after the wedding, where they engaged the Rangers in a gun battle. The Rangers wounded several of Lowell’s men and killed another before disappearing into Mosby’s Confederacy. The next morning, Lowell rode up to Leesburg with ambulance wagons and carefully moved his men back to their camp that evening.

Fittingly, Melville closed his poem with, “To Mosby-land the dirges cling.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically-acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of thirteen books, including his new bestselling book on the Civil War The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations, currently in the front display of Barnes and Noble stores nationwide or on the Father’s Day Table. His other bestsellers include: The Indispensables, The Unknowns, and Washington’s Immortals. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickKODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.