Henry Alfred Kissinger died on Wednesday, November 29, at the age of 100, leaving behind a diplomatic legacy that is America’s answer to Klemens von Metternich, the conservative statesman who restored a balance of power to Europe in the aftermath of the upheavals caused by Napoleon.

Kissinger was a conservative internationalist, one who favored engagement over neutrality, but who prioritized American interests in doing so, and sought to create stability that would ultimately work to America’s advantage.

Kissinger’s great achievement was to split communist China from the Soviet Union. He engineered a thaw in relations that saw President Richard M. Nixon, who had built his political career as a tough anti-communist, visit China in 1972.

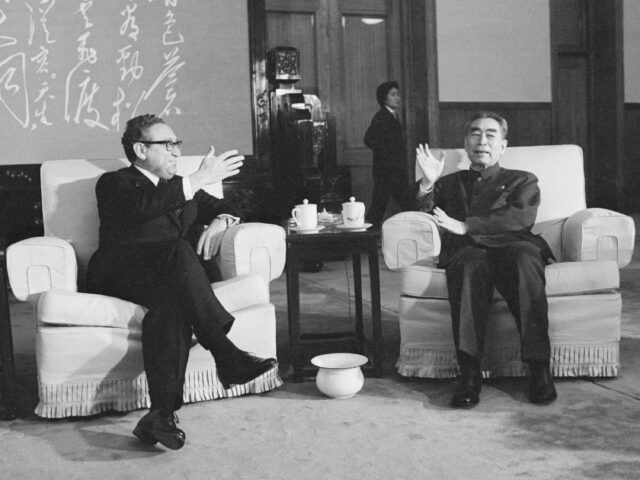

Henry Kissinger and Zhoi Enlai relax on large chairs at a reception given in the Great Hall of the People, after Kissinger’s successful shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East brokered a truce.

Though one of his successors, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, later declared that the policy of engaging China had been a failure, the fact was that it isolated the USSR and weakened it, helping to precipitate the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellites two decades later.

At the same time, Kissinger was reviled by the left for his role in expanding the Vietnam War to Cambodia, and for backing right-wing dictatorships and militias around the world as a counterweight to Soviet rebels and regimes. Critic Christopher Hitchens, later a supporter of the Iraq War, imagined trying Kissinger for war crimes.

Whether admired or loathed, Kissinger was a symbol of American realpolitik, to borrow a term Otto von Bismarck, the 19th century statesman who built Kissinger’s native Germany.

White House advisor Henry A. Kissinger (left) tells newsmen at the White House 10/27 that President Nixon will journey to Peking early next year and provide “an opportunity to make a new beginning” in relations with mainland China. At right is Nixon’s press secretary, Ron Ziegler.

Born Heinz Alfred Kissinger to a Jewish family in Fürth, Kissinger came to the U.S. as a teenage refugee from the Nazis in 1938. He would return to Germany in an American uniform, working as an interpreter for the U.S. Army.

When he returned to the U.S., he studied at Harvard: his 400-page undergraduate thesis on history and politics remains a legendary achievement. He became a widely respected scholar in the emerging field of international affairs before being tapped as an adviser to the U.S. government.

In 1968, Nixon named Kissinger as National Security Advisor. He retained that title, unusually, when Nixon appointed him as Secretary of state in 1973.

Almost immediately, Kissinger faced his first major crisis in the Yom Kippur War, when Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel on October 6, 1973. While Nixon made sure that Israel had the ammunition to fight, Kissinger sought to restrain Israeli victory so as not to upset the balance of power and his effort at détènte with the Soviet Union.

Portrait du Premier Ministre israélien Golda Meir et du diplomate américain Henry Kissinger en mai 1974 en Israël. (Photo by William KAREL/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Kissinger’s role in that crisis is memorably portrayed by Liev Schreiber in the recent film Golda. Kissinger was often opposed to Israel’s position.

Supposedly, the following exchange occurred, as recalled by a correspondent to the New York Times: “During an impasse in Middle East negotiations, Dr. Kissinger said, ”Golda, you must remember that first I am an American, second I am Secretary of State and third I am a Jew.” Golda Meir responded, ”Henry, you forget that in Israel we read from right to left.”

By then, Kissinger had already won the 1973 Nobel Peace Price for his work in helping to craft an agreement with North Vietnam to end the Vietnam War — a key Nixon campaign promise.

His reputation was only slightly marred by the final, chaotic American withdrawal from Saigon in 1975. By then, President Gerald Ford was in the Oval Office, having been elevated after Nixon’s resignation in the Watergate scandal. Ford retained Kissinger as Secretary of State, a sign of the esteem in which he was held.

Such was Kissinger’s commitment to realpolitik that he once famously dismissed the idea of pressuring the Soviet Union to allow Jews to emigrate.

As Tablet magazine recalled in 2010:

“The emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy,” [Kissinger] said. “And if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.”

Responded Nixon: “I know. We can’t blow up the world because of it.”

President Ronald Reagan took a different approach, placing the moral case against the Soviet Union at the center of U.S. opposition to communism.

Former Soviet prisoner Natan Sharansky, who was jailed for trying to emigrate to Israel, would later say that Reagan’s shift was the key to bringing down the Soviet “evil empire”: the brutal punishment of those who simply wanted to leave the supposed communist utopia undermined the moral foundation of a system that had kept half the world in thrall.

For nearly half a century after he left public office, Kissinger continued to consult for American and world leaders, and to write about foreign policy.

As a pillar of the foreign policy establishment, he drew criticism from some conservatives. He came to symbolize the rise of a corporatist class within the Republican Party, revolving around Wall Street and Washington, resisting populist reforms.

“[H]e was Nelson Rockefeller’s agent, no friend of the Republican conservatives,” the Times wrote in 1982, when Kissinger criticized Reagan’s foreign policy in Europe. (He thought Reagan was too timid in his support for Poland against the USSR.)

His 2014 book World Order drew criticism from some conservatives for its somewhat aspirational view of international harmony — though Kissinger emphasized in the book that the sovereignty of the nation-state remained the best guarantor of order.

He praised America’s idealism — which was often missing from his “realist” foreign policy — but also noted the limits of idealism in foreign affairs, and pointed out its failures in the Middle East, where the project of spreading democracy had largely failed.

Last year, he took a controversial stance on the Ukraine war, arguing against George Soros and advocating for a settlement that would acknowledge Russia’s role in Europe. He was concerned, as ever, about keeping Russia and China apart.

Though hardly an idealistic view, the ongoing stalemate, and the rising Russia-China axis, suggest Kissinger had a point.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of the new biography, Rhoda: ‘Comrade Kadalie, You Are Out of Order’. He is also the author of the recent e-book, Neither Free nor Fair: The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

This post has been updated to include Kissinger’s views on Soviet Jewry.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.