While C. Boyden Gray was not well known nationally, he was a household name in Washington, D.C. But don’t hold that against Boyden, who died, at age 80, on May 21.

Yes, he was a fixture in D.C., but he was not beloved by the Beltway, as attested by this sour obituary in The Washington Post.

You see, Boyden was a career-long opponent of over-regulation, and as such, he was in opposition to the “business model” of the federal government, which is, of course, a well-fed bureaucracy. Red tape has been accumulating since the U.S. formalized itself in 1789; not surprisingly, the bureaucratic accretion has exceeded the bureaucratic erosion. Yet in the 20th century, the growth of the federal government went from arithmetic to exponential.

As a result, a whole new field of political science emerged. In 1948, University of California political scientist Dwight Waldo published The Administrative State: A Study of the Political Theory of American Public Administration, which remains the touchstone of the field. Writing 75 years ago, Waldo was mostly admiring of this phenomenon, observing that the administrative state had deep political and intellectual roots. Most notably, it originated in the progressive thinking of Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president, who put great faith in the ability of intellectuals—bureaucrats, scientists, and social scientists—to remake the world.

As Waldo put it, “This faith in science and the efficacy of scientific method thoroughly permeates our literature on public administration. Science has its experts: so we must have ‘experts in government.’” To be sure, there’s nothing wrong with expertise, and yet we must realize that the expertise we most need is common sense. After all, human nature is not science. Come to think of it, “political science” is not science; it’s a tricked-up wannabe suffering always from “science envy.” So, Waldo’s notion that the administrative state was based on scientific principles has been, well, disproven. The administrative state offers the illusion of precision and expertise and nothing more. This blunt reality was well evident by the 1970s, when Ronald Reagan referred to Washington, DC, as “puzzle palaces on the Potomac.”

Boyden, born in 1943 to a tradition of public service—his father held a variety of important posts in the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, rising to be White House National Security Adviser from 1958 to 1961—was an eyewitness to much of the growth of the administrative state, including, of course, its submerged doppelgänger, the Deep State.

A Tarheel by birth, he aced law school at the University of North Carolina. In the 1960s, he clerked for the Chief Justice of the United States; and by the 1970s, he was lawyering for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (this was long before it went woke).

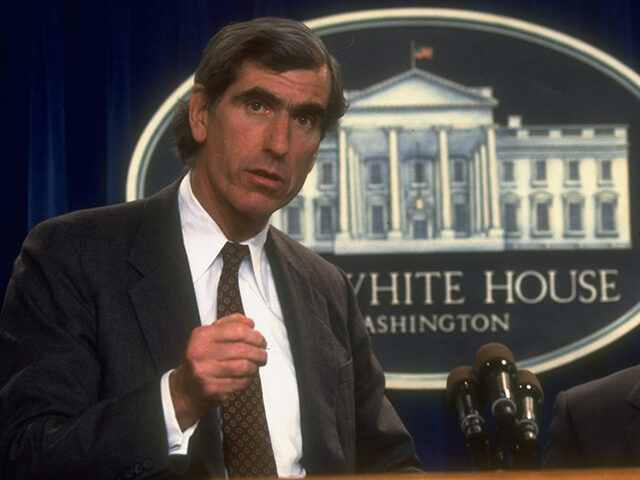

Then, in 1981, Boyden started work as counsel to Vice President George H.W. Bush. That’s where I met him—in the halls of the Old Executive Office Building (OEOB, since renamed the Eisenhower Executive Office Building), just across a driveway from the West Wing. I’m not a lawyer, and I was much Boyden’s junior, and yet his energy and enthusiasm radiated to all high and low. He knew that getting things done in D.C. must be a team effort; you have to enlist and persuade, and even the peons can help.

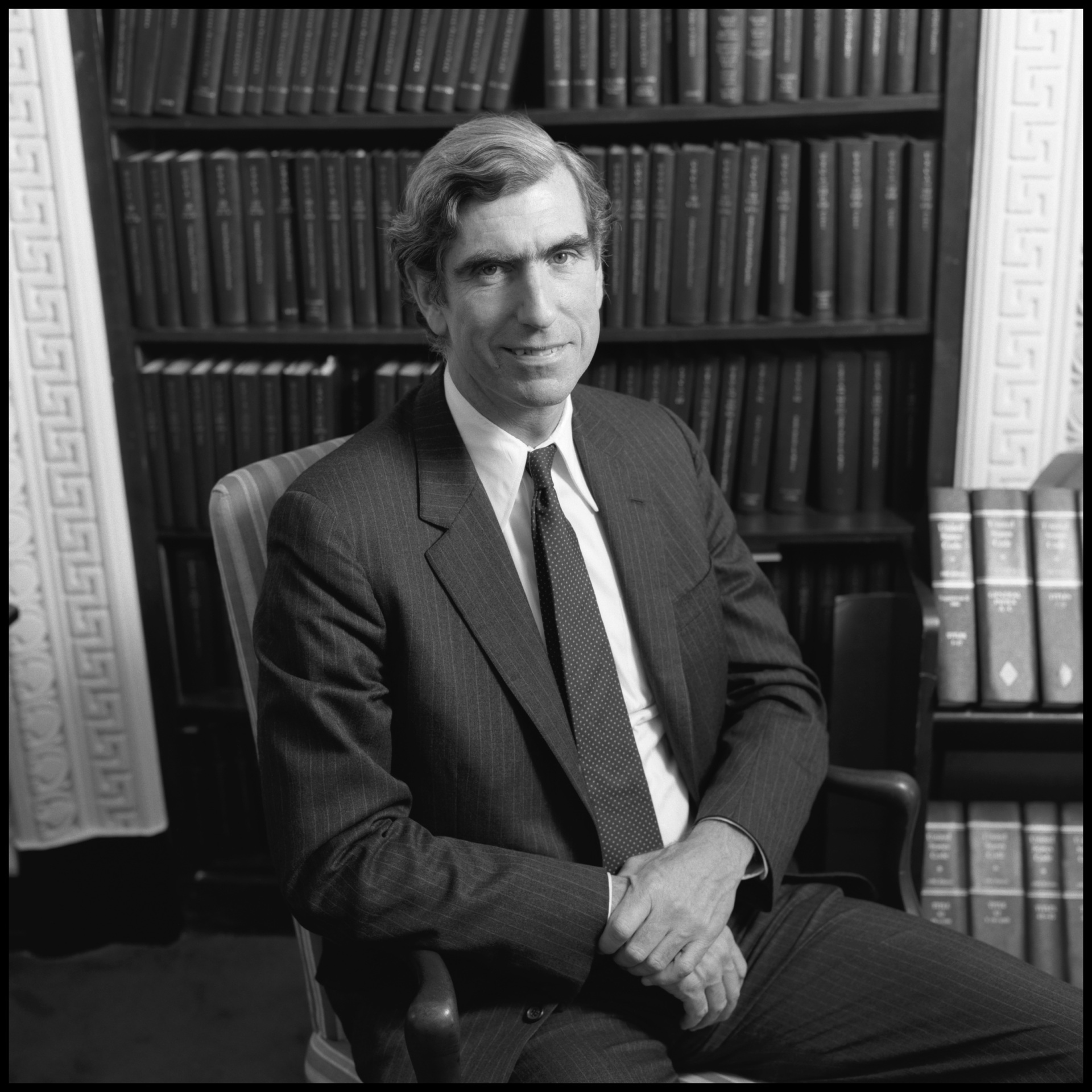

American attorney and White House Counsel under President George H.W. Bush C. Boyden Gray in his office in Washington, DC, in November 1988. (Janet Fries/Getty Images)

Any White House lawyer must confront the humdrummery of the law, and yet from the get-go, Boyden had a special mission: doing the spadework for the Reagan administration’s deregulation task force. Right out of the box in 1981, the Reagan-Bush team scored a win when oil price controls, left over from the Carter administration, were lifted. The result: production went up, and prices went down. The Reagan economic boom was getting its first legs.

Needless to say, in a pro-regulation city, deregulation was controversial. And yet Boyden survived the slings and arrows because he kept his nose clean—and because he knew his stuff. As one news account from 1983 put it,“knowledgeable officials say Mr. Gray is the man who has been chiefly responsible for prodding Government agencies to help fulfill the President’s promise.” That streamlining work continued all through the 1980s. Boyden successfully prodded the Food and Drug Administration to move faster on medicines that treated everything from strokes to AIDS.

After Vice President Bush became President Bush in 1989, Boyden moved from the OEOB to the West Wing. And from that perch, all his past work continued, and there was more. No doubt the most important new challenge was fulfilling the president’s responsibility to select new federal judges. Traditionally, such selections had been made in consultation with the American Bar Association (ABA). But even back then, the ABA was moving left. This shift sort of sneaked up on the Bush administration. On the urging of his then-Chief of Staff John Sununu, President Bush appointed David Souter to the Supreme Court in 1990. Dismayingly, Souter turned out to be a left-liberal.

President George Bush walks across the White House South Lawn on Oct. 12, 1991, with White House Counsel C. Boyden Gray (left) and Chief of Staff John Sununu. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

President George Bush (right) listens to his Supreme Court Justice nominee Judge David Souter during his introduction at a White House press conference on July 23, 1990. (Dirck Halstead/Getty Images)

White House Counsel C. Boyden Gray (fourth from the left) listens as President George Bush introduces his Supreme Court justice nominee Judge David Souter at a White House press conference on July 23, 1990. (Diana Walker/Getty Images)

After that, Boyden and his legal allies—including the many activist brains at the Federalist Society—put their foot down: There needed to be a better process for vetting prospective judges. The results were immediately apparent, as Republicans freed themselves from the proto-woke grip of the ABA.

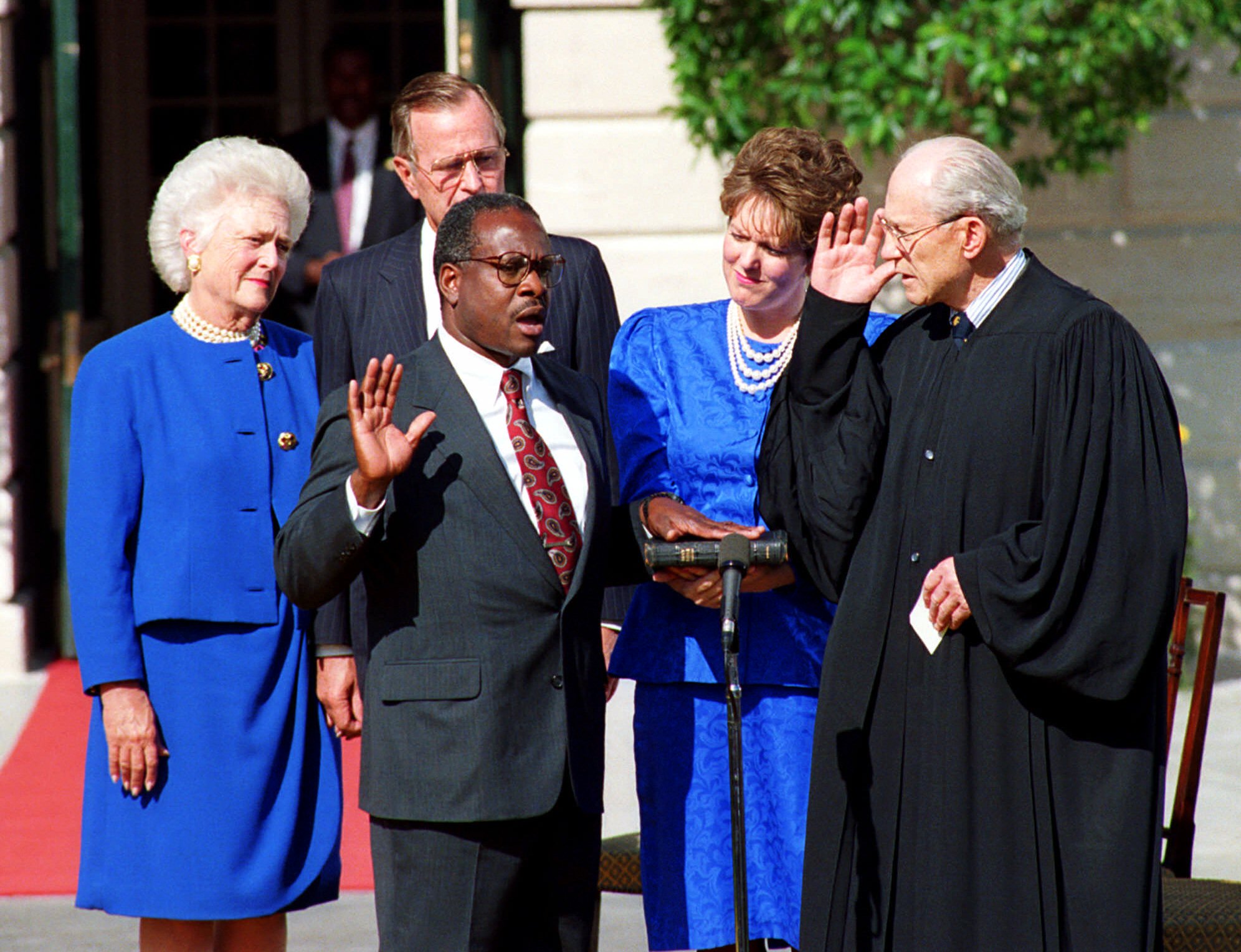

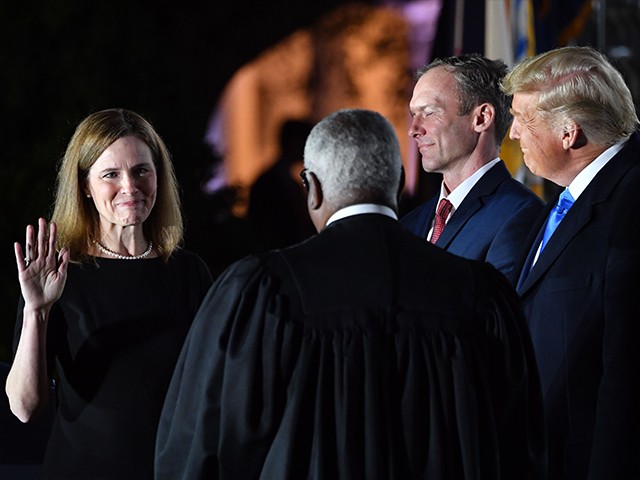

The following year, Bush 41 appointed Clarence Thomas, that stalwart rock of Constitution-minded conservatism—and so began a new era of Republican judicial savvy. Indeed, ever since, Republican presidents have mostly hewed to the conservative line about appointing only carefully vetted candidates; the cry of “No more Souters!” rang loudly. The result has been that the five justices put on the Supreme Court by Republicans since Thomas—John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—have joined with Thomas to form a conservative constitutionalist bloc. And behind-the-scenes credit goes to legal warriors—including Boyden, who had returned to the private sector after Bush 41’s defeat in 1992.

Clarence Thomas is sworn in as a Supreme Court Justice at the White House on October 18, 1991, by Justice Byron White. Looking on from left is First Lady Barbara Bush, President George Bush, and Virginia Lamp Thomas. (AP Photo)

Amy Coney Barrett is sworn in as a Supreme Court Justice by Justice Clarence Thomas during a ceremony at the White House on October 26, 2020, with President Donald Trump and Jesse M. Barrett observing. (Nicholas Kamm/Getty Images)

Yet perhaps the subject area of greatest interest to Boyden was the administrative state. Although the idealistic enthusiasm that Dwight Waldo expressed back in 1948 has long dissipated, the federal bureaucracy chugs along. Google’s Ngram history metric tells the tale of the administrative state’s rise and rise. Indeed, the administrative state still maintains the illusion of expertise, despite such obvious failures as the Iraq War and the COVID mask mandates and lockdowns. And what admin-state brainiac thought that funding Chinese gain of function research on viruses was a good idea? In fact, still thinks it’s a good idea?

To keep up the good fight against statist hubris, Boyden endowed the C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University. That might be a mouthful to say, but its purpose can be summed up with concision: build the legal and intellectual muscle to push back against the administrative state.

C. Boyden Gray speaks at a panel discussion hosted by The Gray Center of George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School on May 25, 2022, in Washington, DC. (Photo: The Gray Center/Facebook)

Poignantly, 2023, the year of Boyden’s passing, marks the 75th anniversary of Waldo’s book on the administrative state.

So, does that mean that the fight is hopeless? That the administrative state will be around forever? In point of fact, Boyden-minded lawyers have won four big Supreme Court victories against federal overreach in the last two years alone—against the Centers for Disease Control, against the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and two against the Environmental Protection Agency. We can read these cases and see how much worse things would be if the good guys hadn’t won.

The truth is, nothing is hopeless. There are no lost causes, and there are no won causes. The fate of everything in human affairs is determined by those who are willing to stand up and do something.

Boyden Gray stood up and made an enduring difference.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.