The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other law enforcement agencies have purchased Americans’ private data, in what could be considered a run around constitutional protections against warrantless searches.

The FBI admitted in March that the agency purchased geolocation data from Americans’ mobile-phone advertising, although the agency said it has moved past that practice after facing legal issues and controversy.

Other government agencies, such as the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), have bought access to American geolocation data.

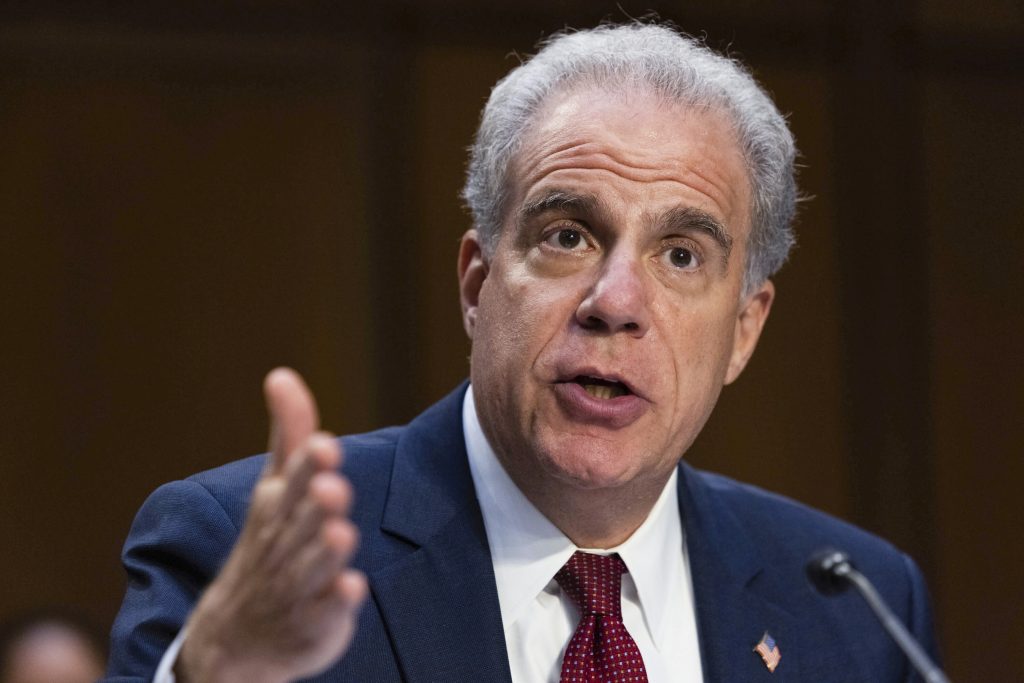

During a House Appropriations Committee hearing in March, Rep. Ben Cline (R-VA) pressed Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz over the FBI’s purchase of Americans’ geolocation data.

Cline asked Horowitz if other parts of the Department of Justice (DOJ) are buying Americans’ private data, describing these reports as “disturbing.”

Horowitz responded, “We’re looking at that, we saw those news stories, we’re looking at that issue.”

Cline then asked, “How did the FBI, and potentially other elements of the DOJ come to believe that buying location information about Americans without a warrant would be legal, especially after the Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. Carpenter, which held that Americans’ location information is protected by the Fourth Amendment?”

Horowitz said, “I think it raises precisely the issues you mentioned, I think what I’m supposing may have happened is before Carpenter happened, the Department took advantage of, at least in some instances, of the ambiguity of the law. Post-Carpenter, of course, that shouldn’t have happened.”

Carpenter v. United States was a landmark 2018 Supreme Court ruling that held that the United States government needed a search warrant to track suspects for an extended period from cellphone carriers.

Horowitz continued, saying that he is not sure about this point about other parts of DOJ purchasing communications or internet records.

At the end of March, Cline pressed Attorney General Merrick Garland during a House Appropriations Committee hearing over this controversy.

Cline asked Garland if he agreed with Horowitz that purchasing Americans’ private data should not have happened post-Carpenter.

Garland said that he does not know any more information than what FBI Director Christopher Wray said when he admitted that the FBI used to purchase Americans’ private communications data.

Cline asked Garland, “Are any parts of DOJ still purchasing location data?”

The attorney general said, “The Department [DOJ] has an internal investigation going on internally to find out which parts,” of the agency might still be engaging in this practice.

Vice reported that the FBI’s Cyber Division, which investigates hackers in the worlds of cybercrime and national security, purchased tens of thousands of dollars in geolocation data.

Vice continued:

Netflow data creates a picture of traffic volume and flow across a network. This can include which server communicated with another, information that is ordinarily only available to the owner of the server or to the internet service provider (ISP) carrying the traffic. Team Cymru, the company ultimately selling this data to the FBI, obtains it from deals with ISPs by offering them threat intelligence in return. These deals are likely conducted without the informed consent of ISPs’ users.

Team Cymru explicitly markets its product’s capability of being able to track traffic through virtual private networks, and show which server traffic is originating from. Multiple sources previously told Motherboard that netflow data can be used to identify infrastructure used by hackers.

A whistleblower approached Sen. Ron Wyden’s (D-OR) office and alleged that the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), the primary law enforcement agency of the Navy, also engaged in this practice. NCIS had told Motherboard that it uses netflow data for “various counterintelligence purposes.”

The Wall Street Journal reported that the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), a branch of the U.S. military, created a program to take advantage of advertising networks. The FBI participated in the JSOC program to test the program’s efficacy, which included the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting.

The Journal continued:

The FBI also purchased a license to a commercial service called Venntel, which allows phone tracking through advertising data, before letting the contract lapse in 2021, according to federal spending records. When the FBI put out a request for proposal last year for a vendor to help monitor social-media chatter, it told bidders that no location-based data feeds should be included in any product sold to the bureau.

The Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) admitted to purchasing Venntel’s data, but said to the Journal, “It is important to note that such information doesn’t include cellular phone-tower data, is not ingested in bulk and doesn’t include the individual user’s identity.”

The military, federal, state, and local police forces have access to bulk data sets from commercial vendors to acquire information, often without court authorization.

Sean Vitka, of Demand Progress, an online privacy and digital rights group, said, “FBI Director Wray’s admission that the FBI secretly purchased Americans’ location data ‘derived from internet advertising’ is both shocking and further proof of the need for Congress to take immediate action to rein in mass surveillance.”

“We should have the right to decide when and how our personal information is shared,” Vitka added.

The Journal noted that the “sheer” amount of data now for sale by data brokers raises the question about how and when the government should or should not be able to purchase Americans’ private data.

Federal and state officials have moved to resolve the questions surrounding law enforcement agencies purchasing information about suspects.

California, Colorado, Connecticut, Utah, and Virginia have passed consumer privacy legislation to protect citizens’ data.

Republicans and Democrats proposed a bicameral solution that would declare geolocation data as sensitive and restrict private industry’s use of that data.

Another group of bipartisan lawmakers, spearheaded by Sens. Wyden and Rand Paul (R-KY), unveiled the Fourth Amendment is Not for Sale Act, which would block law enforcement agencies from buying access to geolocation data without a warrant.

The controversy over government agencies purchasing Americans’ private data without a warrant is just one part of the larger national dialogue over privacy advocates wanting to rein in the federal government’s surveillance powers. Lawmakers want to curb Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), a law that the federal government believes allows intelligence agencies to collect communications of targeted foreigners. The American intelligence agencies’ collection of foreign communications may also lead to incidental or even targeted collection of American citizens’ information, which civil liberties advocates often say amounts to warrantless surveillance of Americans.

During one hearing, Rep. Darin LaHood (R-IL), a member of the House Intelligence Committee, said he believed he was the unnamed congressman that was surveilled by the FBI:

I think that the report’s characterization of this FBI analyst’s action as a mere misunderstanding of the querying procedures is indicative of the culture that the FBI has come to expect and tolerate. It is also indicative of the continued failure to appreciate how the misuse of this authority is seen on Capitol Hill. And I want to make clear, the FBI’s inappropriate querying of a duly-elected member of Congress is egregious and a violation that not only degrades the trust in FISA but is viewed as a threat to the separation of powers.

“I have had the opportunity to review the classified summary of this violation and it is my opinion that the member of Congress that was wrongfully queried multiple times solely by his name was in fact me. Now, this careless abuse of this critical tool by the FBI is unfortunate,” he added.

Sean Moran is a policy reporter for Breitbart News. Follow him on Twitter @SeanMoran3.