Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (R) stirred controversy last month when he objected to the contents of the College Board’s new Advanced Placement (AP) course on African-American Studies.

Florida law prohibits radical philosophies like Critical Race Theory, which describes America as fundamentally racist, from being taught to children. So he was well within his rights — and seems to have encouraged some improvements.

For his trouble, DeSantis has been smeared as a racist and a fascist who is opposed to the teaching of black history — as if “black history” must be whatever the left decides it is.

This week, the College Board released its current framework for the AP course — which does include radical ideas such as “intersectionality,” which holds that black people must back other “oppressed” groups, even when doing so is against their own interests.

However, the AP framework also includes material on “black conservatives,” which is encouraging (provided their ideas are described accurately, and that they are not dismissed, per usual, as sellouts to white racism).

Overall, I found the framework to be — at first glance — balanced, and comprehensive. My own objection to it is that is too specialized: this is material for juniors and seniors in college, with a basic grounding in U.S. history.

I am skeptical of the idea that focusing on any group is appropriate at the high school or early college level — and I say this as someone with a graduate degree in Jewish Studies.

It is correct to teach black history as part of U.S. history, among other groups in the American mosaic. But today we are at risk of losing a common identity as a nation. Students should be encouraged to learn more about black history, but they need to grasp basic U.S. history first.

My own story may prove illustrative.

I was born in South Africa, though I grew up in Chicago. So when I was a (public) high school senior, classmates suggested I check the “African-American” box on college applications, thinking (not incorrectly) that doing so would boost my chances.

I never did; I understood I was neither an intended nor a deserving beneficiary of affirmative action. But I did take an interest in African-American studies.

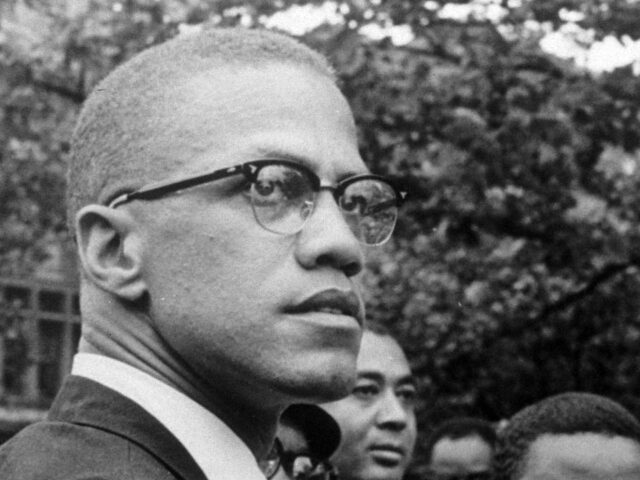

I remember how it began — in February 1992, when the school library set up a display of books for Black History Month. I was intrigued by The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which I read — over and over again.

I disagreed with much of what Malcolm X believed — especially about Jews — but I was impressed by his personal journey to faith, which led him, bravely, to move past racial nationalism before he was assassinated.

A few months later, I attended the morning meeting of our high school’s African-American club. I was the only white person in the room; my presence caused a few curious glances.

Afterward, the president of the club approached me and asked, politely, what I was doing there. I told her about my background — and I told her that I wanted to learn more about the African-American experience.

She welcomed me to join, and I did.

The club’s yearbook picture the following spring — with one white face in the ranks — caused some controversy among my peers. But I stayed in the club — more an observer than a participant. Over the years, I learned things about my peers’ experience of high school that I never would have understood otherwise — especially the feeling that black students had to overcome unique obstacles on their way to academic achievement.

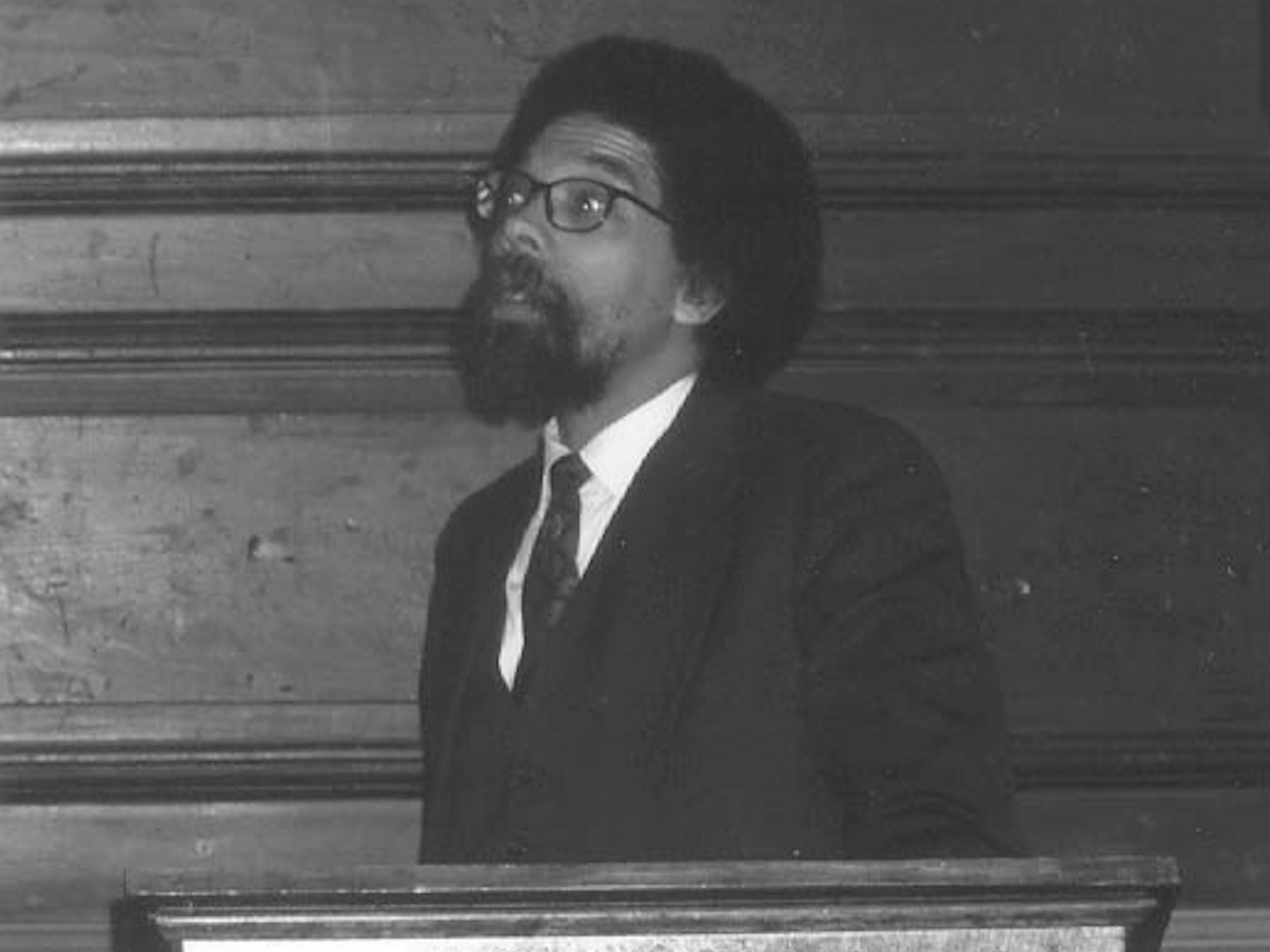

I arrived at Harvard in the fall of 1995 at the same time as Cornel West, who had been hired away from Princeton to join the “dream team” of African-American studies under Henry Louis (“Skip”) Gates Jr.

I took classes with him over two years; of all the professors on campus, he alone was able to weave political theory into current events. And unlike most dry college lectures, his classes were thrilling debates, grand contests of ideas.

When I began to explore the “real world” of politics, and of life, I found that very little of West’s idealism was reflected in reality. My approach to the world was still empirical — I majored in environmental science, as well as social studies — and I believed in measuring theories by their results.

West’s ideas didn’t work. I absorbed that lesson more fully after graduation, when I returned to South Africa on a Rotary Foundation scholarship.

I had been fascinated by South Africa’s transition to democracy, as seen from abroad. And in the new South Africa, I saw many of my left-wing ideals being implemented.

My excitement turned to concern and then to horror as I saw some of the consequences of those ideas — children abandoned to the ravages HIV, human rights abuses condoned next door in Zimbabwe, poverty festering as ruling-party elites lined their pockets.

Yet I still learned whatever I could. I studied Xhosa, and I tutored kids in a township library. I read the writings of Rhoda Kadalie — who later became my mother-in-law.

I spent less time tutoring as I began working as a political speechwriter in the South African Parliament — but as I watched the clash of ideas there, I began to realize there was a huge gap in my education: I knew nothing of the alternatives to the left.

When I returned to the U.S. to study law at Harvard, I took some of the undergraduate courses I had missed — especially the Greek and Roman philosophers. I lacked that grounding; it was not taught in high school, or in an AP course, and neither Plato nor Aristotle were on display in the school library.

I do not regret the roundabout path that I took, but I regret that it took me so long.

We need to put the basics first; the rest is enrichment.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of the new biography, Rhoda: ‘Comrade Kadalie, You Are Out of Order’. He is also the author of the recent e-book, Neither Free nor Fair: The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.