Today, Americans of all stripes are constantly bombarded with an insidious propaganda campaign against our shared history. From Critical Race Theory to ripping down historical statues, our national story is being rewritten as irredeemably sinful. These efforts have taken a particularly racialized characteristic by implying that Black history is somehow distinct from, or in opposition to, “American history” itself, rather than an integral part of it.

Looking back to our past, we realize that this narrative of scorn isn’t how the great heroes of American history saw their homeland. The American patriots we still honor today—including African Americans—did not see Black history as something apart from American history; in fact, they saw the principles of the American Founding, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, as the key to their story of perseverance.

Fredrick Douglass, in his 1852 address “What To The Slave Is The Fourth Of July?” called the principles of the Declaration of Independence “saving principles,” the Constitution a “glorious liberty document,” and Independence Day “the very ringbolt in the chain of your yet undeveloped destiny.” He knew that liberty and equality were the keys to the American Founding, and he knew that any nation founded on such revolutionary propositions could not remain a slaveholding nation forever.

Rather than berate America’s founders, Douglass went on to call them “brave men,” “statesmen, patriots, and heroes.” He urged his audience to “honor their memory” because “they seized upon eternal principles.”

According to Douglass, through these very principles—fundamentally American principles— “liberty and humanity” rather than “slavery and oppression” would be final.

Civil War reenactors Fredrick E. Smith, 52, of Youngstown, OH, (L) and Kevin Douglass-Green, great-great-grandson of Fredrick Douglass, stand on either side of an original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by President Abraham Lincoln during its unveiling ceremony at the African American Civil War Memorial Museum May 20, 2005 in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

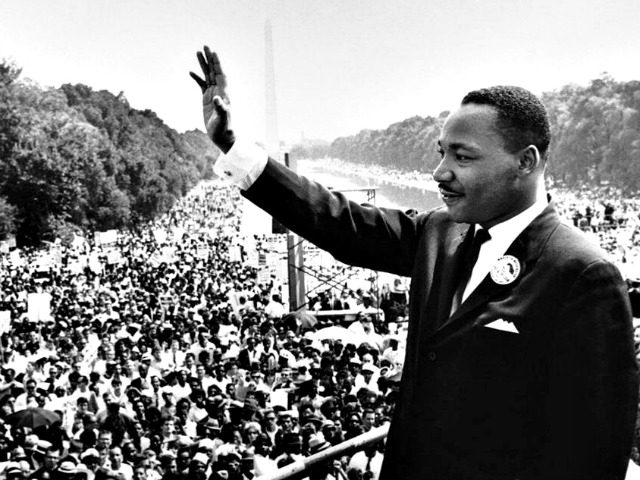

Just over 100 years later, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. King’s vision, he emphasized, “is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

Like Douglass, King mentioned with favor the “magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence,” calling them “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”

To King, slavery, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and all other forms of racial inequality were ultimately a betrayal of American principles. King’s dream, he said to more than 200,000 people from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, was that “one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

American civil rights leader and Baptist minister Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 – 1968), dressed in black robes and holding out his hands towards the thousands of people who have gathered to hear him speak near the Reflecting Pool in Washington, DC during the Prayer Pilgrimage. (Hulton Archive/Getty)

Both Douglass and King saw the course of American history as the ironing out of America’s founding principles, even with all of the ugly bumps and bruises that came along the way. Equality, in their minds, was a promise baked into America’s very DNA—a promise that took far too long to fulfill, but a promise that America pursued nonetheless.

This embrace of Americanism can be seen throughout the entirety of American history.

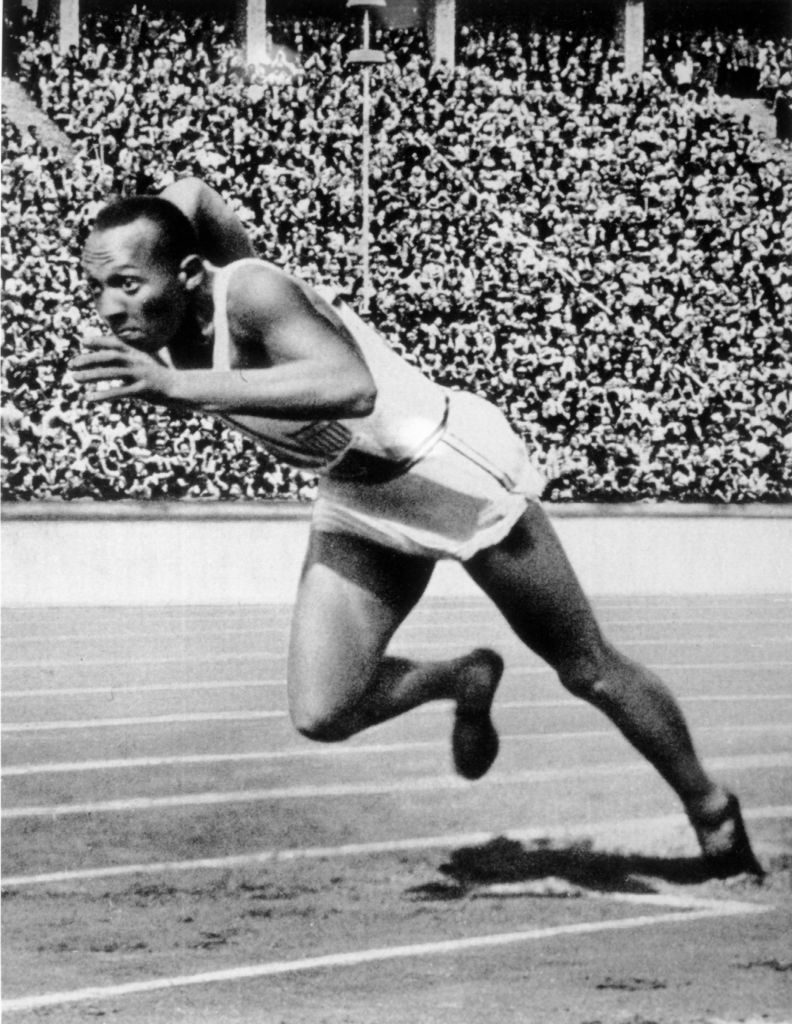

It is in the blood of Crispus Attucks falling as a martyr to spark the American Revolution, it is in the steely resolve of the Massachusetts 54th regiment charging Fort Wagner to change the course of the Civil War, it is in the ingenuity of Elijah McCoy revolutionizing the locomotive industry with his automatic lubrication system, it is Jesse Owens humiliating Nazism on the world stage, and it is at the tails of the Tuskegee airmen patrolling the skies of North Africa and the Mediterranean.

Jesse Owens of the USA in action in the men’s 200m at the 1936 Summer Olympic Games held in Berlin, Germany. Owens won a total of four gold medals in the Olympics. (Getty Images/Getty Images)

These examples, and countless others like them, testify to the truth that Black history is an integral part of American history—not set apart as something in contradiction to the story of American life, but a vital part of our national identity.

We remember the past to lead us through the present, and we seek inspiration by looking back to the example these great figures left for us to follow. They realized that, as Americans, we have more in common than separates us. But we can only be genuinely united when we rediscover our shared American identity, rooted in our Founding principle: “all men are created equal.”

Today, just like at the time of Douglass and King, these principles are our “ring bolt.” They are our “promissory note.” These truths inspired the words and deeds of heroes of the past, and these same principles guide us through the future.

This Black History Month, let’s remember that Black history is American history and come together to reunite under our American principles—just like our forefathers did before us.

Ken Blackwell is the Chairman of the Center for Election Integrity at the America First Policy Institute. He is an adviser to the Family Research Council and Chairman of the Conservative Action Project.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.