When Bob Dole ran for president in 1996, he lost by a wide margin, gaining barely more than 40 percent of the national vote. And yet interestingly, the victor that year, Bill Clinton, was himself held to less than 50 percent of the vote.

So where did the other votes go? Most of them went to businessman Ross Perot, who ran a quixotic third party presidential campaign, gaining 8.4 percent of the ballots cast. Perot’s ’96 campaign had little message other than free-floating anti-establishmentarianism; so most of his votes came at the expense of challenger Dole, as opposed to incumbent Clinton. Indeed, given that Perot’s percentage of the popular vote (8.4), was almost identical to Dole’s deficit against Clinton (8.5 percentage points), it’s possible that without Perot in the race, Dole would have won. If so, then there would have been no second Clinton term, and the Arkansan would be remembered as just a slick but unimportant president, sandwiched between two heroes of World War Two, George H.W. Bush and Dole.

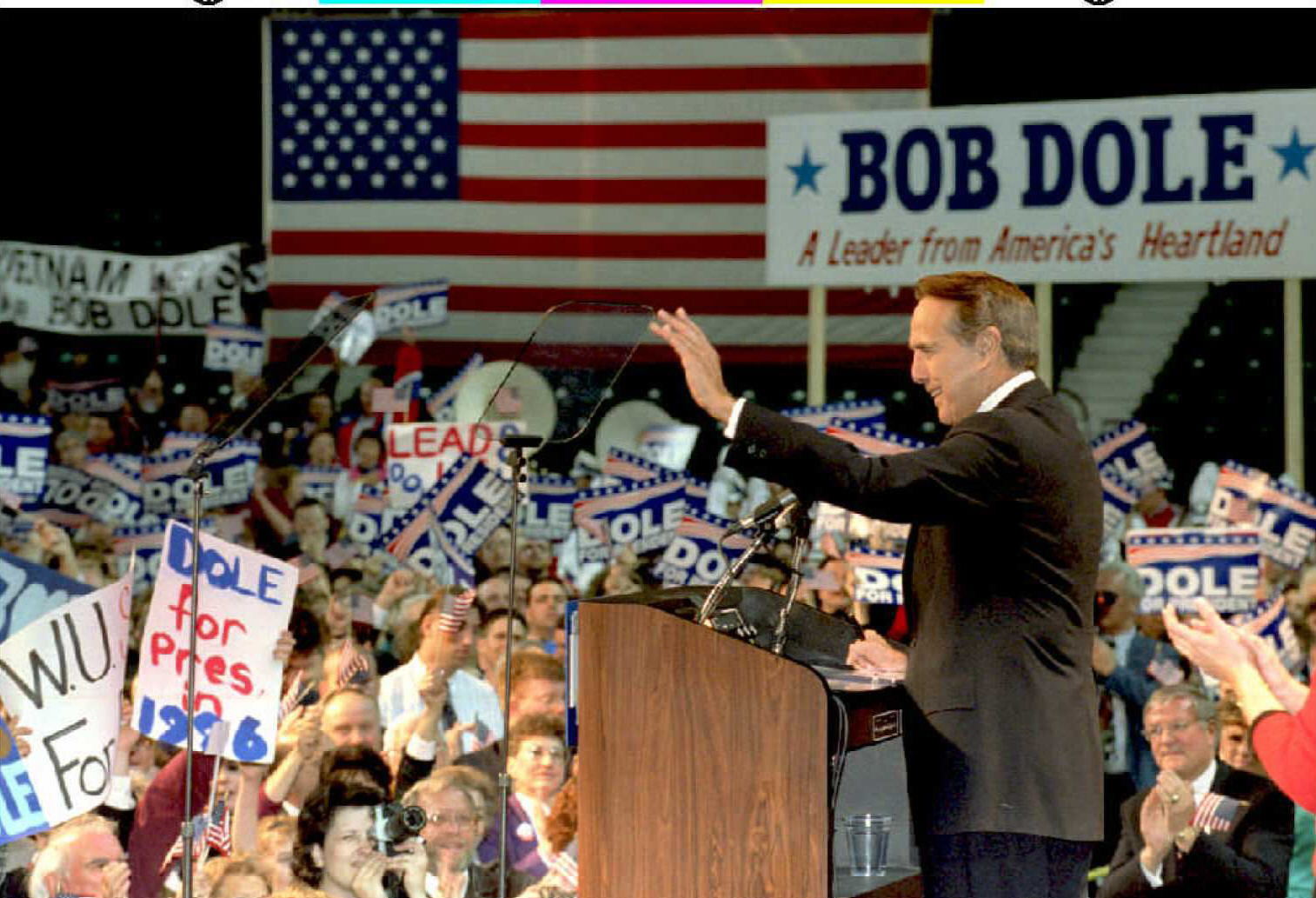

Sen. Robert Dole (R) announces his third bid for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, April 10, 1995, in Topeka, Kansas. (CHRIS WILKINS/AFP via Getty Images)

Still, if we’re playing the “what if?” game, we can further say that if the epic film Saving Private Ryan had come out in 1994, as opposed to 1998, Dole might well have won the presidency in ’96, Perot or no Perot.

That’s because that Steven Spielberg movie stands as a milestone in the popular understanding of World War Two and in our upward appreciation of the men who fought in it. (Women were certainly a part of the war effort, in uniform and on the homefront, and yet there were no women in the harrowing opening combat scene at Omaha Beach or in any other mission in Normandy.)

Ryan was when the awesome, gruesome reality of World War Two finally came home to Americans, when civilians got a sense of what real combat was actually all about.

To be sure, in the first five decades after World War Two, the men who fought that war were well remembered and applauded, and seven veterans of the conflict—Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and Bush 41—were elected to the White House. And yet the full dimensions of their military achievement and of their sacrifice somehow escaped the popular imagination.

For many Americans, Ryan fixed that.

In that same year, 1998, NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw published The Greatest Generation, which touched on at least some of the same mighty themes; as Brokaw wrote admiringly, ”It is, I believe, the greatest generation any society has ever produced.”

Around that same time, the works of historian Steven Ambrose gained momentum; one of his volumes was Band of Brothers: E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne from Normandy to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, which in 2001 was made into a widely watched HBO miniseries.

So we can see: If the warm feelings about the Good War had warmed further a little sooner, Senator Dole might also have been President Dole.

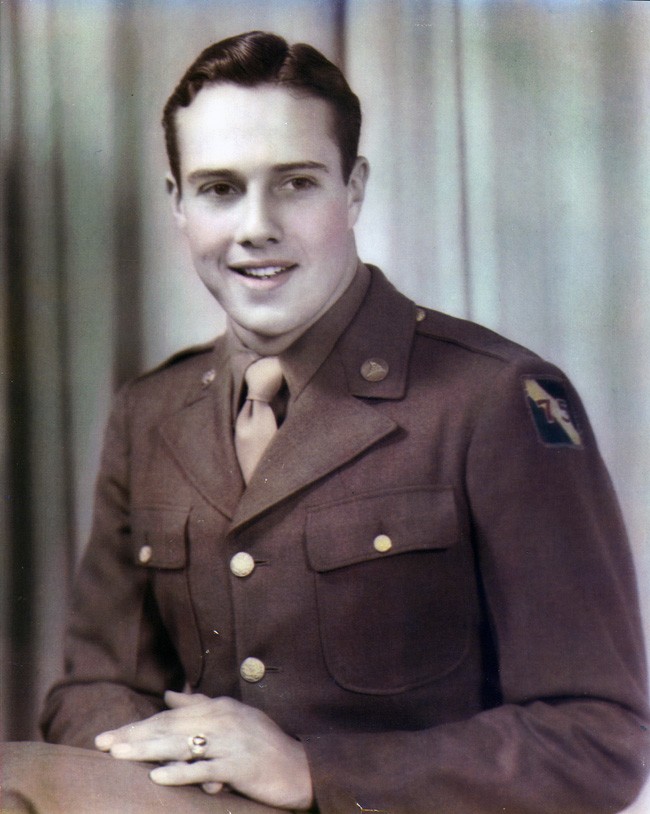

U.S. Army Second Lieutenant Robert Dole in his brown dress uniform, circa 1944. (Robert and Elizabeth Dole Archive and Special Collections)

But then, of course, nobody ever said that life was fair. That’s a lesson of World War Two, a conflict that produced such bitter works of literature as Catch-22 and The Naked and the Dead, both massive best-sellers, both written by combat vets.

In fact, any G.I. of that era knew the bad of the Good War, including such sour and ironic acronyms as FUBAR and SNAFU. Heck, even the military brass acknowledged these realities; a Private SNAFU was the animated star of more than two dozen training films made from 1943 to 1945.

Bob Dole knew all about the weird, even savage, impact of circumstance in wartime. Although he wanted to be a doctor, the Army made him an engineer. Although he hailed from the flat prairies of Kansas, he was assigned to a mountain infantry division. And so then he was sent to the Italian campaign in the European Theater of Operations, there to fight in the Alps. Second lieutenant Dole was a long way from the Jayhawk wheat fields.

The fighting in Italy is much less remembered than D-Day and the liberation of France and then Germany, and yet nevertheless, that “sideshow” still cost the U.S. more than 100,000 casualties—and Dole became one of them on April 14, 1945, less than a month before the end of the war.

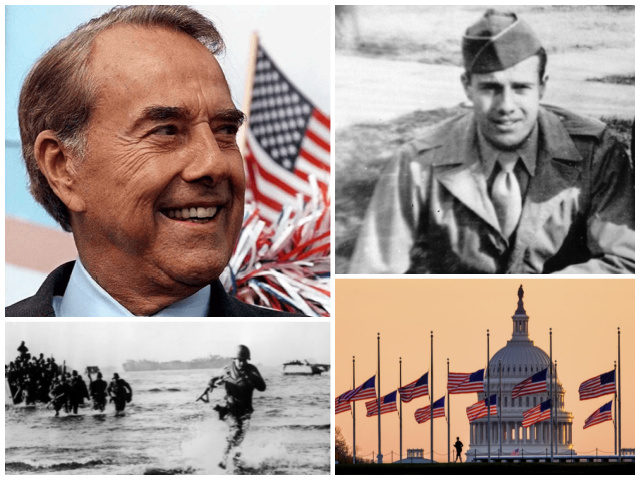

Bob Dole (left) and his childhood friend “Bub” Dawson (right) posing in dress uniform circa 1944. (Robert and Elizabeth Dole Archive and Special Collections)

American soldiers of the Fifth Army dashing ashore during the establishment of a beachhead, South of Rome, on the West coast of Italy, in May 1944, during World War II. (STF/AFP via Getty Images)

U.S. troops of the 5th Army, 1st Division, loading tanks onto land from naval ships during World War Two, prior to the Battle of Anzio, Italy, 1944. (A. E. French/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Returned to stateside, the grievously wounded Dole would spend the next three years in military hospitals. Such an experience would have a profound effect on anyone, and so it did on Dole. As a man with a lot of pain and only one good arm, Dole focused his energy into a funny-yet-cutting wit—as they say, comedians are usually channeling their own pain—and a vaulting ambition for public service.

Bob Dole is seen recovering in an Army hospital in 1945. Dole was severely injured in combat. An exploding shell smashed his right shoulder, crushed his collarbone, punctured a lung, and damaged vertebrae that paralyzed Dole from the neck down. Upon his return to the U.S., Dole spent 39 months in hospitals. His condition was so severe that his doctors doubted that he would live. (Robert and Elizabeth Dole Archive and Special Collections)

And that’s how he got himself elected to the Kansas state legislature and then to the U.S. Congress. Furthermore, that’s how he become the Republican senate leader for more than a decade, as well as the chairman of the Republican National Committee. And came to be named twice to the national GOP ticket (in addition to his 1996 presidential run, he was the vice presidential nominee in 1976).

Politically, fate wasn’t kind to Dole. And yet even if he didn’t reach the pinnacle that he sought—nobody ever said life was fair, and nobody was right—he made much of his life, such that he will be honored by lying in state in the Capitol Rotunda. A grateful nation can do that much for an unfortunate son who overcome so much bad luck and adversity.

Yet in the meantime, the hardy few survivors from the Greatest Generation—all of them in their 90s or older—will enjoy much warmth this December 7, the 80th anniversary of the Japanese sneak attack that plunged the U.S. into World War Two.

And the rest of us can bask in their stoic dignity and earned glory, even as they typically insist that the real heroes were the ones that died, on the beaches, in the jungles, in the skies—or in the burning waters at Pearl Harbor 80 years ago.

An explosion at the Naval Air Station, Ford Island, Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack, December 7, 1941. Sailors stand amid wrecked watching as the USS Shaw explodes in the center background. (Fox Photos/Getty Images)

The American destroyer USS Shaw explodes during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, home of the American Pacific Fleet during World War II, December 7, 1941. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

There’s not much we can do for these oldsters now, except to assure them that not only will they continue to be cared for, but so also will we always look out for their lost comrades in arms.

Speaking of finding the lost, on December 4 it was heartening to see an article in Politico headlined, “How DNA Solved One of the Final Mysteries of Pearl Harbor.”

As the piece detailed, respectful and resourceful Pentagon experts have been using the latest medical science to identify most of the hundreds of sailors who died aboard the U.S.S. Oklahoma on that date which will live in infamy. Originally, the remains recovered from the ship could not be identified and so were interred in mass graves in Hawaii. And yet now, all these decades later, forensic technology has so much improved, it’s possible, for example, that the bones of Mess Attendant Second Class Jesus Garcia, killed at 21 aboard the Oklahoma, can be identified and properly interred at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

Of course, they haven’t been able to identify them all; once again, life is not fair.

Yet as a nation, we have the power to make any situation at least a little bit fairer and better. We can pledge to do right by the recent memory of Bob Dole, the distant memory of Jesus Garcia, and the memory of all of our heroes, living and dead, from all our wars.

That’s a worthy mission on Pearl Harbor Day and every day.

Flags lowered to half-staff in honor of former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas fly in the breeze at sunrise on the National Mall with the U.S. Capitol in the background on December 6, 2021. (AP Photo/J. David Ake)

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.