The critical shortages of essential commodities that America suffered at the start of the pandemic were more than an inconvenience—they were a national wake-up call. In 2020, America could not even produce something as basic as enough N-95 masks.

Currently, supply chains cannot secure crucial semiconductors used in cars, and rare earth metals essential in everything from missiles to smartphones could be choked off at any moment. Ships waiting to unload their cargos line the west coast. Supply chain failures threaten critical pharmaceuticals.

Some feel government, bigger government, is the solution—making people even more dependent and less self-reliant, further eroding personal and national sovereignty.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, the Founders faced a similar situation. But they fought back in a novel manner that united Americans in a way never before seen in history. They boldly threw down a nonimportation and exportation agreement against the greatest economic power on earth.

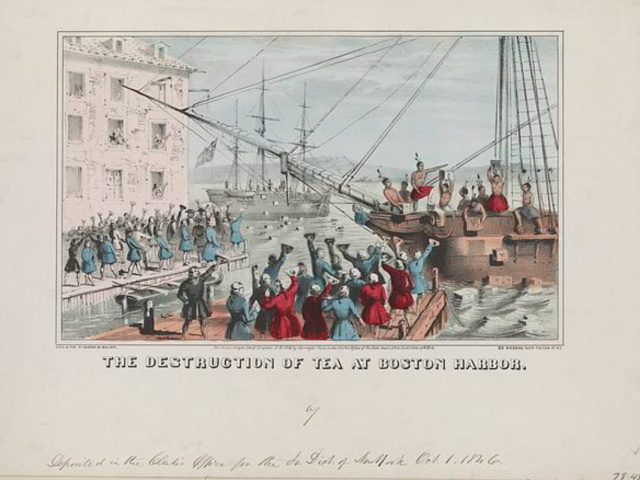

After the Boston Massacre and the Intolerable Acts passed by Parliament to punish Boston for the Boston Tea Party, Americans put economic teeth behind their anger. Many colonists set aside their short-term financial self-interest. They waged economic war against the most potent trading power in the world at the time, just as they had done successfully several years earlier when opposing the Stamp Act.

In 1774, the First Continental Congress had never been more united. Instead of isolating the radicals as the British had hoped, the Intolerable Acts increased sympathy for Boston. These Acts, among other things, closed the port of Boston, throwing thousands out of work, installed judges loyal to the Crown, and dissolved the Patriot government. Support for the city began to unify the colonies as nothing before had—if the Crown could disenfranchise Massachusetts, none of the colonies was safe.

On October 20, 1774, via the Articles of Association, a nonimportation and nonexportation agreement, Congress declared a boycott on British goods and agreed not to export goods to Britain, Ireland, or other British colonies if Parliament did not repeal the Intolerable Acts. The articles struck at the heart of British trade. The Continental Congress had declared economic war on their imperial rulers, so heavily dependent on selling goods manufactured in Great Britain to the colonies and using raw materials from the North America to make those goods.

Within Marblehead, Massachusetts (then that colony’s second-largest port) and other towns, the American Patriots soon established committees of inspection to enforce the economic rules of the Articles of Association. The Articles also discontinued the slave trade, which Great Britain monopolized. Article Two stated: “We will neither import nor purchase, any slave imported after the first day of December next, after which time, we will wholly discontinue the slave trade, and will neither be concerned in it ourselves, nor will we hire our vessels, nor sell our commodities or manufacturers to those who were concerned in it.” These are hardly words of individuals fighting to expand and further the institution of slavery. Massachusetts, the heart of the political revolution, was actually a hotbed of abolition.

As America today, the colonies in 1774 boasted one of the highest standards of living in the world. Two-thirds of the white population owned land, in contrast to only one-fifth of their fellow brethren in Britain. Additionally, Americans had one of the highest literacy rates in the world; two-thirds of them could read and write. The American population, about two and a half million, doubled every twenty-five years, combined with explosive economic growth. They understood that economic growth and the engine of capitalism were crucial to building the wealth intertwined with freedom and liberty. Freedom could not manifest if they were dependent on imports from Great Britain.

America’s greatest vulnerability in 1774 involved Britain’s campaign to eliminate American sources of gunpowder—outlawing it and trying to secure all its sources in the colonies. The spark that ignited the Revolution would be the conflict at Lexington and Concord over securing gunpowder and other munitions. Eerily, the United States does not contain a single primary lead smelting plant used in the manufacture of projectiles and a large portion of the primers used in munitions flows from an overseas source. Fighting sustained conflicts against multiple adversaries becomes challenging if those very adversaries can choke off microchips, rare earth materials, and principle components essential for munitions. In short, they have tremendous influence and sway on America’s foreign policy.

Cities along the eastern seaboard, including Marblehead, maintained the embargo on British goods and refused to export their raw materials to the Crown. The economic warfare had a devastating effect on Britain. Some factories closed because they did not have raw materials from the colonies and had diminished markets for British goods. Americans rejected dependence on goods from the Crown and developed their own industry—the origins of an economic engine the likes of which the world had never seen.

Freedom and liberty as well as soft and hard power would flow from this engine later in the 20th century when the United States would be the arsenal of democracy. Patriot Americans threw their support behind Boston by signing the nonimportation-exportation agreement regarding goods from Britain. The merchants of Marblehead, Massachusetts went even further. Although designated by the Intolerable Acts as the new American primary point of entry, Marblehead refused to profit from their fellow countrymen’s punishment in Boston by offering their own wharfs and storehouses free of charge to Bostonians, placing patriotism above profit.

The full story of this pre-Revolution economic warfare is now told in the new bestselling book, The Indispensables: Marblehead’s Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the Country, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware. The book is a Band of Brothers-style treatment of the regiment and the leading revolutionary citizens from Marblehead, a unique largely unknown group of Americans who changed the course of history.

Political revolution that flowed from Boston and Marblehead became the zeitgeist. Most colonists in New England supported the embargo and further demonstrated their unprecedented unity by their defiance of British General Thomas Gage’s prohibition on town meetings. When Gage dared to detain the leaders of a meeting in Salem, he found at his door the next day over 3,000 armed colonists who warned the governor that he “must abide by the consequences” if he sent the leaders to prison, for “they would not be answerable for what might take place.”

These self–sacrificing, fiercely independent Founding Fathers of the 1770s would scarcely recognize the America scurrying to feed the mouths of those sharpening their knives that will inevitably cut our throat. Money U.S. consumers spend on goods is being funneled directly into military spending by those who wish us harm. They understood the connections among autonomy for crucial goods and independence and sovereignty. Today, however, American multinational corporations and policymakers are increasingly more invested in the overseas markets of adversary nations and protecting outsourced supply chains than in strengthening America. In our leaders, in some cases, we see outright appeasement. Deindustrialization, outsourcing core industries, and dependence on imports have become national security issues. The United States would not have a supply chain crisis if more of our products were produced in America.

America’s Founders recognized the dangers of dependency and fought it with the core of their being. We enjoy the fruits of their hard-won battles. The present situation demands the similar hard choices and sacrifices they made for us, or the strong, independent nation they fought for will no longer be recognizable.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of twelve books, including The Indispensables, which is featured nationally at Barnes & Noble, Washington’s Immortals, and The Unknowns. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.