Mask-wearing mandates for young children in schools offer many positive benefits according to a recent New York Times op-ed claiming masks provide “distinctive opportunities for learning and growth,” improve social and cognitive skills, strengthen self-control and attention, help conquer habits such as nose-picking and nail-biting, and empower children to “practice caring.”

In the Wednesday piece, Dr. Judith Danovitch, an associate professor and research psychologist who studies children’s cognitive and social development, attempts to depict child mask-wearing as a practice with wide-ranging benefits, dubbing a classroom full of mask-wearing people “a great opportunity” for children.

Titled, “Actually, Wearing a Mask Can Help Your Child Learn,” Danovitch begins by noting the concerns of parents of young children, specifically the negative impact of wearing masks which can “impair children’s ability to learn language and socialize.”

Such concerns, according to Danovitch, are “understandable but unwarranted.”

A child wearing a face shield and mask stands in the cafeteria of Medora Elementary School. (Jon Cherry/Getty Images)

“Although scientists don’t have much data yet on how wearing masks during a pandemic affects children’s development, there is plenty of reason to believe that it won’t cause any harm,” she assures.

Danovitch then attempts to support her stance by citing education in other cultures where faces can be partially or nearly fully covered.

“Children in cultures where caregivers and educators wear head coverings that obscure their mouths and noses develop skills just as children in other cultures do,” she writes.

“Even congenitally blind children — who cannot see faces at all — still learn to speak, read and get along with other people,” she adds.

She then goes further, claiming that masks actually provide a benefit to children in learning environments.

“Indeed, there is good reason to believe that wearing a mask at school could actually improve certain social and cognitive skills, helping to strengthen abilities like self-control and attention,” she writes.

Admitting that masks are not necessarily “preferable,” she notes that they provide unique opportunities to support a child’s education.

“Masks are inconvenient, uncomfortable and bothersome,” she writes. “But as long as they are needed, we should take advantage of the fact that they offer distinctive opportunities for learning and growth.”

Regarding language learning, Danovitch explains how obscuring one’s mouth accentuates a child’s focus on other facial features, such as eyes, which boosts another form of communication.

“It’s true that masks cover our mouths and that seeing mouth shape and movement contributes to language development in infants,” she writes. “But learning how to communicate involves a lot more than mouths — a reality that masks accentuate.”

“It turns out that looking at eyes is at least as important as looking at mouths to understand whom you are looking at and what they are trying to convey,” she adds, claiming that eye-tracking research supports such a stance.

CDC wants to open schools this fall, but wants unvaccinated students to wear masks. (STRF/STAR MAX/IPx)

“In fact, children with a stronger capacity to discern people’s thoughts and emotions based on their eyes alone exhibit greater social-emotional intelligence,” she claims.

The associate professor also details how children rely on other sometimes subtle cues, including “prosody, gesture and context,” to comprehend others’ thoughts as well as new word meanings.

“A classroom full of people wearing masks is a great opportunity for children to practice paying attention to those cues, such as a peer’s tone of voice or a teacher’s body language,” she argues.

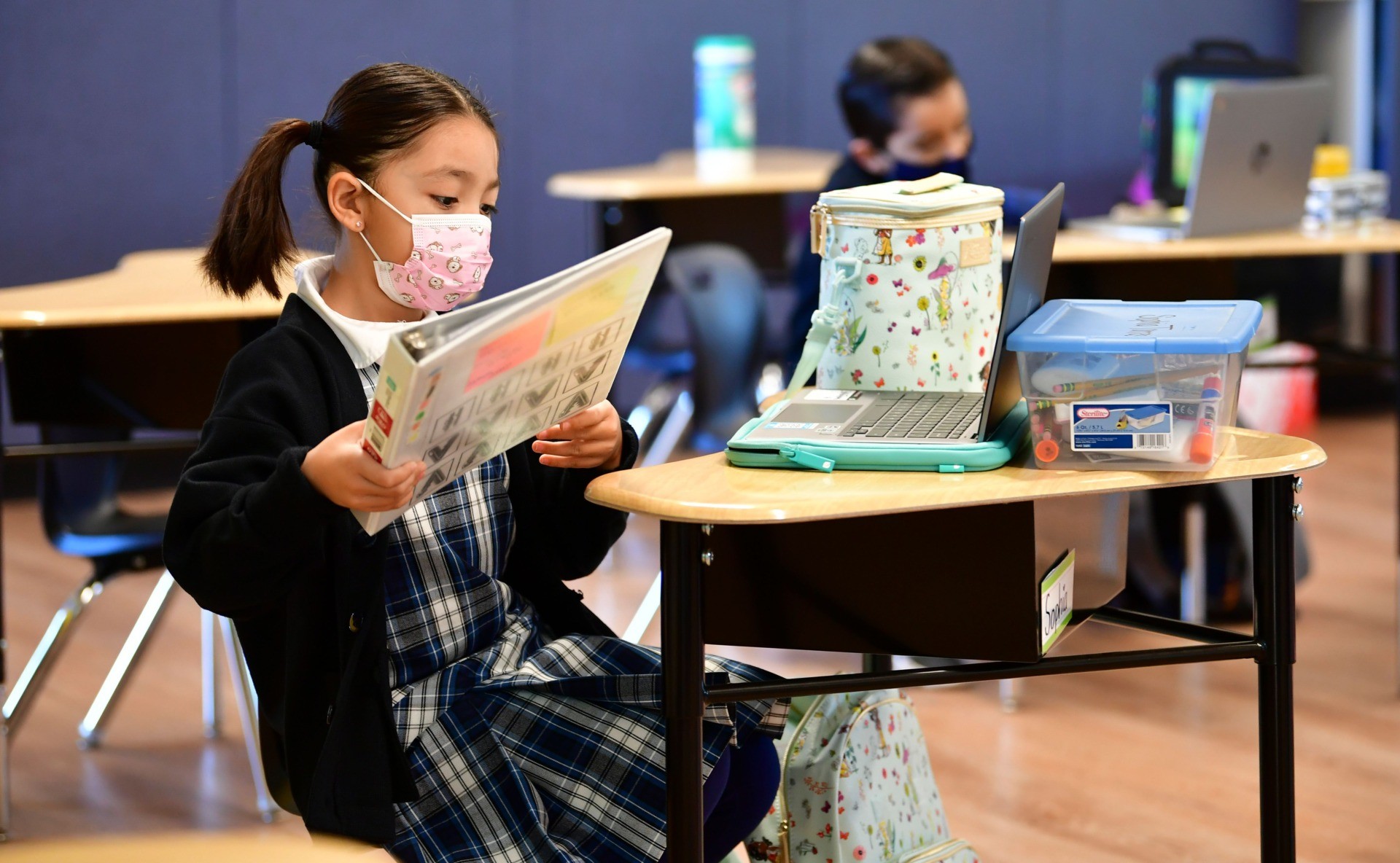

First grade students prepare for class at St. Joseph Catholic School in La Puente, California. (FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP via Getty Images).

Danovitch lists additional benefits of mask-wearing for children, notably that they can notice their own bodies and behaviors in greater detail and gain a greater sense of control over them.

“Wearing a mask can also help teach children to pay more attention to their own bodies and physical behaviors,” she writes.

“Keeping a mask on over the course of a school day involves the kind of self-control and self-regulation that many children find challenging,” she adds. “Younger children must inhibit the urge to pull off their mask, and older children must be mindful of when their mask is slipping down or when it’s OK to take it off.”

She continues by claiming that research on self-control suggests that children who master those skills needed to endure mask-wearing will “grow up to be better at achieving their long-term goals, solving problems and handling stressful situations.”

“For children who habitually bite their nails or pick their nose, a mask could also be precisely what they need to kick the habit,” she adds.

Perhaps most importantly, Danovitch writes, mask-wearing during a pandemic provides an opportunity to “practice caring” for one’s community.

“By preschool, children can understand that invisible ‘germs’ can cause illness and that behaviors such as hand-washing can keep germs from spreading,” she writes, adding that mask-wearing can empower young children to help protect others.

As for older children, Danovitch claims that mask wearing can “teach more sophisticated ethical concepts like duty and sacrifice.”

“Stressing that the discomfort and inconvenience of mask wearing are forms of generosity and public service might motivate children to address other social problems in their lives, like bullying,” she writes.

She concludes by holding parents, teachers, and caregivers responsible for how children regard mask-wearing in schools.

“Ultimately, how children feel about wearing masks at school, and how much they psychologically benefit from wearing them, is going to depend on how the parents, teachers and caregivers around them present the issue,” she writes.

The essay comes as mask requirements for children in schools have become a heated issue across the country, with numerous protests erupting in response.

Currently, millions of students in Florida, Texas, and Arizona are being required to don masks in classes as school boards in mostly Democratic locales impose mandates in defiance of their Republican governors.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), headed by Dr. Rochelle Wolensky, advises vaccinations and masking for children as part of its “Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention in K-12 Schools.”

Last month, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) stated that the Biden administration wants kindergartners “muzzled with a mask,” yet when it comes to people crossing the border illegally, “they don’t give a damn about COVID at that point.”

Earlier this month, the White House said officials were not concerned about the psychological effects of forcing children to wear masks in school to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

When asked by a reporter if there were any concerns from President Joe Biden’s administration about forcing children to wear masks in school all day, White House press secretary Jen Psaki replied, “No. There’s not.”

Last week, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) claimed keeping children in masks all day is a perfectly appropriate tactic for combatting the coronavirus.

In a series of tweets last Thursday, the organization that previously urged people to respect a child’s preferred gender argued that masks have virtually no negative effect on a child’s development, dismissing parental concerns as being either overblown or nonexistent.

On Thursday, Rep. Greg Murphy (R-NC), a physician specializing in urology, told Breitbart News that the CDC’s “guidance” for masking children to prevent coronavirus transmission is unsupported by scientific analysis or data.

“I wish I could say this particular intervention led to this good result, but the science tells us that that’s just not true,” he said.

Follow Joshua Klein on Twitter @JoshuaKlein

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.