The U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) on Thursday upheld the Arizona statute that bans ballot harvesting and a policy that throws out votes cast by persons in precincts in which they do not reside.

Justice Alito wrote for the majority in a 6 to 3 decision that neither Arizona’s HB 2023 banning ballot harvesting nor the policy outlawing out-of-precinct voting violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act which bans racial discrimination.

Alito was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, Barrett, and Kavanaugh.

Justice Kagan wrote the dissent, joined by Justices Breyer and Sotomayor.

“In these cases, we are called upon for the first time to apply Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to regulations that govern how ballots are collected and counted. Arizona law generally makes it easy to vote. All voters may vote by mail or in person for nearly a month before election day, but Arizona imposes two restrictions that are claimed to be unlawful,” Alito wrote in his majority opinion.

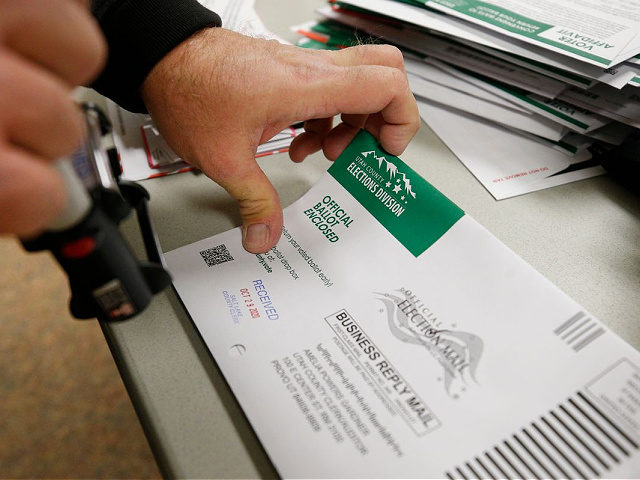

“First, in some counties, voters who choose to cast a ballot in person or on election day must vote in their own precincts or else their ballots will not be counted. Second, mail-in ballots cannot be collected by anyone other than an election official, a mail carrier, or a voter’s family member, household member, or caregiver,” Alito continued:

The regulations at issue in this suit govern precinct-based election day voting and early mail in voting. Voters who choose to vote in person on election day in a county that uses the precinct system must vote in their assigned precincts.

For those who choose to vote early by mail, Arizona has long required that “[o]nly the elector may be in possession of that elector’s early ballot.” In 2016, the state legislature enacted House Bill 2023 (HB 2023), which makes it a crime for any person other than a postal worker, an elections official, or a voter’s caregiver, family member, or household member to knowingly collect an early ballot –either before or after it has been completed.

Having describe the issues at the core of the case, Alito continued.

“One strong and entirely legitimate state interest is the prevention of fraud. Fraud can affect the outcome of a close election, and fraudulent votes dilute the right of citizens to cast ballots that carry appropriate weight,” Alito wrote:

Fraud can also undermine public confidence in the fairness of elections and the perceived legitimacy of the announced outcome. Ensuring that every vote is cast freely, without intimidation or undue influence is also a valid and important state interest. This interest helped to spur the adoption of what soon became standard practice in this country and other democratic nations the world round: the use of private voting booths.

Alito then addressed the key argument made against the Arizona election practices, that they violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and were therefore racially discriminatory.

“Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act provides vital protection against discriminatory voting rules, and no one suggests that discrimination in voting has been extirpated, or that the threat has been eliminated. But Section 2 does not deprive the States of their authority to establish non-discriminatory voting rules, and that is precisely what the dissent’s radical interpretation would mean in practice,” Alito wrote.

That key phrase in Alito’s majority opinion–that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act “does not deprive the States of their authority to establish non-discriminatory voting rules,”– will likely play a role in judicial decisions in the lawsuit filed by the Department of Justice in federal district court last week against the State of Georgia, which alleged that the state’s new Election Integrity Act of 2021 (SB 202) violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

In light of the principles set out above, neither Arizona’s out-of-precinct rule nor its ballot collection law violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act . Arizona’s out-of-precinct rule enforces the requirement that voters who choose to vote in person on election day must do so in their assigned precincts. Having to identify one’s own polling place and then travel there to vote does not exceed “the usual burdens of voting.” On the contrary, these tasks are quintessential examples of the usual burdens of voting.

The burdens of identifying and traveling to one’s assigned precinct are also modest when considering Arizona’s “political processes” as a whole.

Section 2 does not require a State to show that its chosen policy is absolutely necessary or that a less restrictive means would not adequately serve the State’s objectives.

In light of the modest burdens allegedly imposed by Arizona’s out-of-precinct policy, the small size of its disparate impact, and the State’s justifications, we conclude the rule does not violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Alito also rejected plaintiffs claims that HB 2023, which bans ballot harvesting, violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act:

The plaintiffs were unable to provide statistical evidence showing that HB 2023 had a disparate impact on minority voters.

Even if the plaintiffs had shown a disparate burden caused by HB 2023, the State’s justification would suffice to avoid Section 2 liability. “A State indisputably has a compelling interest in preserving the integrity of its election process.”

Limiting the classes of persons who may handle early ballots to those less likely to have ulterior motives deters potential fraud and improves voter confidence. That was the view of the Bipartisan Commission on Federal Election Reform chaired by former President Jimmy Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker. The Carter-Baker Commission noted that “[a]bsentee balloting is vulnerable to abuse in several ways: . . . Citizens who vote at home, at nursing homes, at the workplace, or in church are more susceptible to pressure, overt and subtle, or to intimidation.

Thursday’s SCOTUS decision reverses the previous decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, which struck down both statutes for what it determined were violations of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as Scotusblog reported:

The court of appeals applied a two-part test, known as the “results test,” to reach that outcome. In the first step, according to the court of appeals, the question is whether the policy or law being challenged disproportionately affects the ability of a racial minority group to “participate in the political processes and to elect candidates of their choice.” If it does, then the next question is whether there is a link between the challenged policy or law and social and historical conditions, creating the inequality in opportunities.

During oral arguments held in March questioning by Justice Barrett, Justice Thomas, Justice Gorsuch, and Chief Justice Roberts suggested they were skeptical of arguments the two Arizona statutes violated Section 2.

Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, refused to defend the two Arizona statutes, and instead, was represented by counsel who argued in oral arguments that the decision by the court of appeals to throw out both statutes should be upheld.

Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, a Republican who has since announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate, defended the two Arizona statutes during oral arguments.

The case is Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, No. 19–1257 in the Supreme Court of the United States. The case was consolidated with Arizona Republican Party v. Democratic National Committee.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.