Western loggers, mill workers, and small communities were shocked when President Biden nominated Tracy Stone-Manning as the Director of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Stone-Manning was part of the notorious domestic eco-terrorist group Earth First! when she was a 23-year-old graduate student at the University of Montana. As an editor of one of the group’s publications, she provided fodder to the faithful who opposed congressionally mandated logging on federal lands. On one occasion, however, she went beyond advocacy. In 1989, she was an accessory to an act of eco-terrorism called tree spiking in an effort to stop the sale of Idaho national forest timber.

Tree spiking occurs when large metal spikes are driven into trees scheduled for harvesting in order to make the trees unsafe to log. The spikes can have a devastating and even deadly effect on a logger or millworker when a chain or circular saw strikes the spikes. For example, on May 8, 1987, a 23-year-old millworker lost several teeth and part of his cheek and jaw after a large band saw shattered when it struck an 11-inch spike driven into a tree.

Tree spiking is truly an act of terror because it is meant to bring fear into the hearts of loggers and millworkers. And bring fear Stone-Manning and her colleagues did. I remember well those days in the late 1980s and early 1990s because my pro bono clients included loggers and their families, mills and their employees, and residents of tiny northwestern towns and counties. Their lives and livelihoods were put at risk by Earth First! and the acts it advocated openly. These eco-terrorists schooled their acolytes in a tactic they called “monkeywrenching,” which involved the sabotage of the heavy machinery used in logging and mining. Little wonder that in 2002, the FBI labeled eco-terrorism as one of the nation’s primary domestic terror threats.

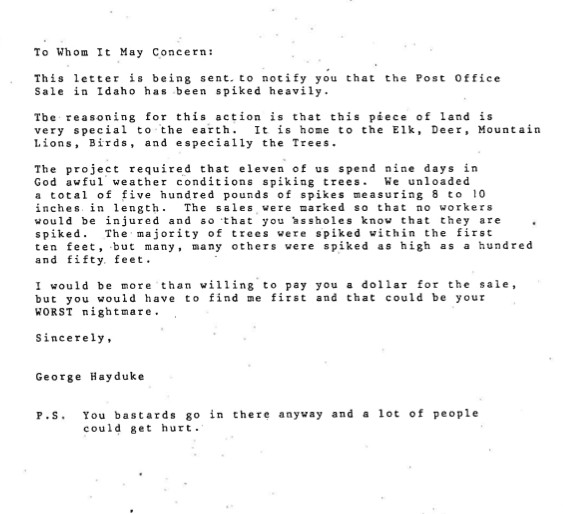

In 1993, in exchange for immunity from federal prosecution, Stone-Manning testified in a criminal trial against John P. Blount, a former roommate and one of her “circle of friends.” She stated that in the spring of 1989, Blount provided her with a letter to send to the U.S. Forest Service warning that “five hundred pounds of spikes measuring 8 to 10 inches in length” were used to spike trees scheduled for the Post Office Creek Timber Sale in the Clearwater National Forest near Powell Junction, Idaho, 40 miles southwest of Missoula, Montana, where Stone-Manning was a student at the University of Montana. She mailed the letter at Blount’s request; however, before doing so, she said she rented a typewriter to retype it because she did not want the letter on her personal computer and because “my fingerprints were all over the original.” (At the trial, her lawyer cut her off before she could elaborate further on that last point, but she finished that sentence about her fingerprints in an interview with the Missoulian.) Blount was convicted of the tree spiking described in the letter Stone-Manning mailed on his behalf, and he was sentenced to 17 months in prison.

The tree spiking letter Tracy Stone-Manning mailed to the U.S. Forest Service in 1989.

In a report on the events that led to the trial, the Missoulian reported that when the U.S. Forest Service received Stone-Manning’s letter in 1989, federal law enforcement officials searched a home in Missoula “where several Earth First activists lived.” And then in the fall of 1989, “prosecutors subpoenaed seven Missoula residents, including Stone-Manning to appear before a grand jury to provide physical evidence, including handwriting and hair samples.” That 1989 grand jury investigation did not uncover enough evidence to charge Blount or anyone else with the crime. Stone-Manning told the Missoulian that in February of 1993, on learning that Blount was finally arrested and charged with the tree spiking, she thought “I was safe” and that “It was time to come forward. It was my responsibility.”

However, Stone-Manning wasn’t the person who turned Blount in to the authorities. According to a Pretrial Memorandum by Assistant U.S. Attorney George Breitsameter, a woman who was assaulted by Blount reported him to a Forest Service special agent in December of 1992; and in doing so, she implicated Stone-Manning. Stone-Manning told the Missoulian in 1993 that she could have been charged with conspiracy (as others in the case were) if not for an immunity agreement she made with U.S. Attorney Maurice Ellsworth, as evidenced by a letter he sent to her attorney. Finally, a decade later in an interview with the Missoulian in 2013, Stone-Manning acknowledged that it was Blount’s ex-girlfriend who reported him for the tree spiking because she feared that he would be released from jail where he was being held for assaulting her.

After her nomination by President Biden, Stone-Manning submitted a written response to the U.S. Senate’s Energy and Natural Resources Committee’s formal questionnaire ahead of her confirmation hearings. In one response, she stated that she had “never been the target of [a federal] investigation.” She wrote this despite the fact that she had been subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury in 1989 and could have been charged with conspiracy in the tree spiking criminal trial in 1993 were it not for her immunity agreement.

Little wonder that Wyoming Sen. John Barrasso concluded that Stone-Manning was “intentionally trying to deceive” the Committee. That Stone-Manning was a target in the tree spiking investigation is clear from the fact that she, along with the other six individuals subpoenaed in 1989, was required to provide handwriting and hair samples to the grand jury.

More significantly, in the questionnaire, she informed the Committee: “In 1989, I testified before a federal grand jury in Boise, Idaho, as part of an investigation into an alleged tree spiking incident related to a timber sale.” She did not disclose the nature of her testimony, but she must not have told the 1989 grand jury about Blount, the letter he gave her, or that she was the one who mailed it. We can deduce this because Assistant U.S. Attorney Breitsameter’s Pretrial Memorandum described the state of the tree spiking investigation at the end of 1989. He wrote that in 1989, “the criminal investigation did not develop any substantial evidence as to the identity of the individuals involved in the spiking.” It was not until December of 1992—three years later—that Blount’s ex-girlfriend turned him in to a special agent with the Forest Service and also named Stone-Manning as the person who sent the letter.

So, Stone-Manning, if not a co-conspirator to the tree spiking, was an accessory after-the-fact to that felony, which she failed to disclose at the time it occurred in the spring of 1989. Secondly, she failed to disclose to the grand jury in 1989 that it was Blount who spiked the trees and she who mailed the letter. Thirdly, she failed to disclose to the Senate Committee that she was indeed the subject of a federal investigation. Furthermore, her answer to the Committee drawing a parallel between her 1989 grand jury testimony and her 1993 testimony at trial was, if not misleading, hardly forthright.

The Senate must, in a bipartisan fashion, reject her nomination. Her role in eco-terrorism in the nation’s forests prevents her from leading the men and women who manage the Bureau of Land Management’s vast timberlands and who work with their colleagues in the Forest Service whose lands were targeted by Earth First!’s eco-terrorism. Just as significantly, she is incapable of leading the BLM’s 300 law enforcement rangers and special agents, who have a sworn duty to enforce the law and are held to the highest professional and ethical standards. That she would sit in judgment of them, which a BLM director must, is an offense.

William Perry Pendley, a Wyoming attorney, led the Bureau of Land Management in the Trump administration. He is the author of Sagebrush Rebel: Reagan’s Battle With Environmental Extremists and Why It Matters Today.