The founding fathers’ unequivocal language in the Bill of Rights that “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed” immediately after the freedoms of religion, speech, and assembly were reinforced was not accidental. The epic battle for control over gunpowder and weaponry between the British government and American colonists motivated much of the action in the Revolutionary War. The fight over gun control is in American’s DNA.

The first shot of the American Revolution was not the infamous Shot Heard Round the World in April 1775 when the Redcoats fired first on American Patriots on Lexington Green attempting to protect their precious store of gunpowder and weapons from British confiscation. Four months earlier, in now-largely-forgotten raids, Loyalists opened fire on a mob of angry colonists attempting to seize control of precious stores of gunpowder. Alarmed by reports that King George III had signed a secret order banning the export of arms, gunpowder, and military supplies, colonists set their sites on the poorly guarded stockpile of weapons and ammunition at Fort William and Mary near Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

The full remarkable story is told among other forgotten but pivotal feats in the new bestselling book, The Indispensables: Marblehead’s Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the Country, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware. The book is a Band of Brothers-style treatment of the regiment from Marblehead, Massachusetts, a unique largely unknown group of Americans who changed the course of history.

Like the conflict on Lexington Green, the drive for the Unum Necessarium of the Revolution—gunpowder—fueled the raid. The Crown had concluded the best way to resolve their differences with America was to disarm New England. The Patriots were determined to prevent it.

When the Marblehead Committee of Correspondence learned from their Salem informants about the Crown’s disarmament plan, John Gerry, brother of Elbridge Gerry, sent a letter via express rider to Son of Liberty and local Portsmouth Patriot leader, John Langdon. He warned local leaders to secure all military supplies as they had already done in Marblehead. Paul Revere soon arrived bearing a similar but more explicit warning–Boston spies had seen British troops secretly leaving the city, suspected of heading for the fort.

Convinced that time was of the essence, Langdon and a few other like-minded men, including Marbleheader Winborn Adams, defied the futile protests of Loyalist governor, Sir John Wentworth. They paraded through the streets of Portsmouth preceded by a fife and drums recruiting volunteers to help them seize the gunpowder located in the King’s fort. Within hours, several hundred Patriot volunteers from both sides of the river clambered into boats on their way to the fort.

Manned by a small garrison of Loyalist and Crown troops, the fort sat on New Castle Island in the mouth of the river boundary between New Hampshire and Maine, as one of the only fortifications of any size in that part of the colonies, the British had used the structure to store their gunpowder and weaponry.

While Langdon gathered his mob, a smaller group of merchants and sea captains attempted to take the fort by stealth, paying a visit to the provincial officer in charge, Captain John Cochran. The unsuspecting officer welcomed the men in to sit by his fire, and they sat swapping sea-faring stories. First two, then five, then four or five more arrived. The captain began to be uneasy. His quick-witted wife, sensing the danger, sidled up to her husband and whispered in his ear while shoving two loaded pistols in his hands. As the officer interrogated his unexpected slew of visitors at gunpoint, more men arrived. The Patriots now outnumbered the scant handful of soldiers on duty at the fort. Cochran announced the obvious: he knew of their intentions to take the fort.

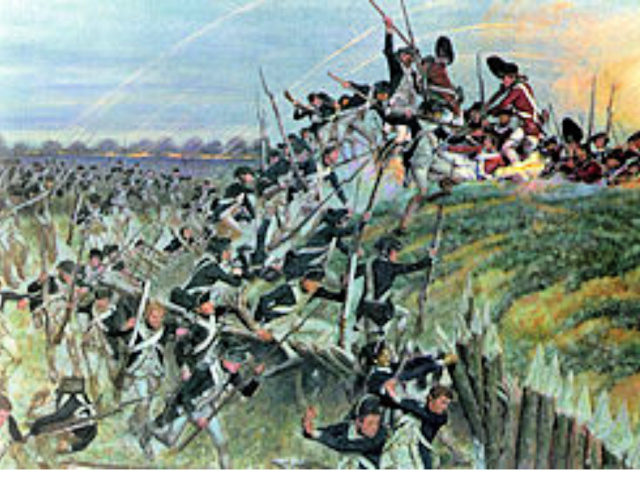

Refusing to be intimidated, the British captain ordered the men to leave and three cannon to be pointed at the gate. Langdon and his crowd now arrived on the island. The colonists had hoped by sheer force of numbers to take control of the powder without a real fight from the desperately outnumbered guard. But facing the reality of staring down the barrel of the cannon, they simply approached and asked to be admitted. Negotiations deteriorated, however, and the mob stormed the fort en masse. True to his promise, Cochran fired his guns and sent four-pound shot hurling into the colonists, arguably, the forgotten first shots of the Revolutionary War. As the attackers dove for cover, most of the cannonballs landed harmlessly on the ground. The soldiers followed the cannon with equally ineffective musket fire. Before they could reload, the colonists scaled the walls.

Despite facing 25-to-1 odds, the defenders of the fort put up a staunch fight in hand-to-hand combat, passionately refusing to surrender until their muskets were literally torn to pieces. Americans were wounded. Even Cochran’s wife joined in the fray. Becoming the first female Loyalist combatant of the Revolution, she shocked the Patriots by snatching a bayonet and briefly freeing her husband from the men holding him captive. They fought side by side until they were both disarmed and retaken as prisoners.

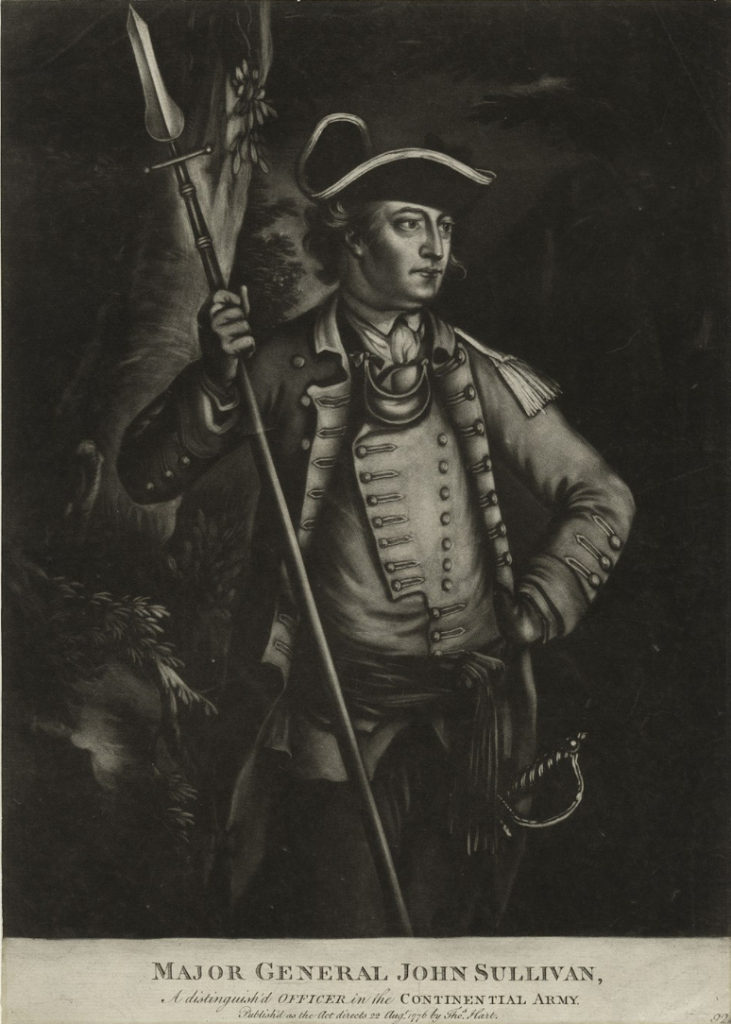

The victorious Patriot mob loaded over 100 hundred-pound barrels of priceless gunpowder into their boats which would prove critical in coming engagements, including Bunker Hill. When faced with the dilemma of what to do with the absconded powder, they turned to militia major and lawyer John Sullivan, one of New Hampshire’s delegates to the First Continental Congress, who split up the powder, sending it to various cities.

Unaware that Sullivan’s loyalties now lay with the Patriots, Governor Wentworth approached him to inquire about whether or not a second raid to seize the remaining cannon at the fort was likely. Sullivan confirmed the Governor’s suspicions, noting that the colonists feared the British planned to use the weapons against them, a claim Wentworth called “a wicked falsehood.”

The next evening, before British reinforcements could answer the Governor’s pleas for help, Sullivan himself led a second attack on the fort. Hundreds of men, including Marbleheader Adams, again loaded into shallow cargo boats and rowed across the frigid moonlit river to the fort. Upon arrival, lawyer Sullivan and Captain Cochran first sparred verbally until the officer agreed to let the attackers inside on the condition that they would only take the munitions belonging to the state of New Hampshire. Once inside the gates, however, the Patriots ransacked the fort and purloined every musket and cannon they could manhandle into their shallow gundalows. Knowing British warships to be en route, the Americans eschewed plans for a third raid and divided the captured booty. They melted back into their homes—forgotten by history but having secured the vital powder and arms by which future victories would be won.

Afterward Sullivan penned a letter to his countrymen reminding them of how Rome disarmed the Carthaginians and asking “whether, when we are by an arbitrary decree prohibited the having arms and ammunition by importation, we have not, by the law of self-preservation, a right to seize upon those within our power, in order to defend the liberties which God and nature have given to us.”

He reminded them how Rome destroyed Carthage after the Carthaginians complied, “[These] brave people notwithstanding they had surrendered up three hundred hostages to the Romans upon a promise of being restored their former liberties; found themselves instantly invaded by the Roman Army. They were told that they must deliver up all their arms to the Romans and they should peaceably [e]njoy their liberties upon their compliance with this requisition.” He signed the letter using the only pseudonym “The Watchman.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of twelve books, including The Indispensables, which is featured nationally at Barnes & Noble, Washington’s Immortals, and The Unknowns. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.