House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made clear she does not believe all women who accuse men of sexual misconduct, a new book on the powerful California Democrat reveals.

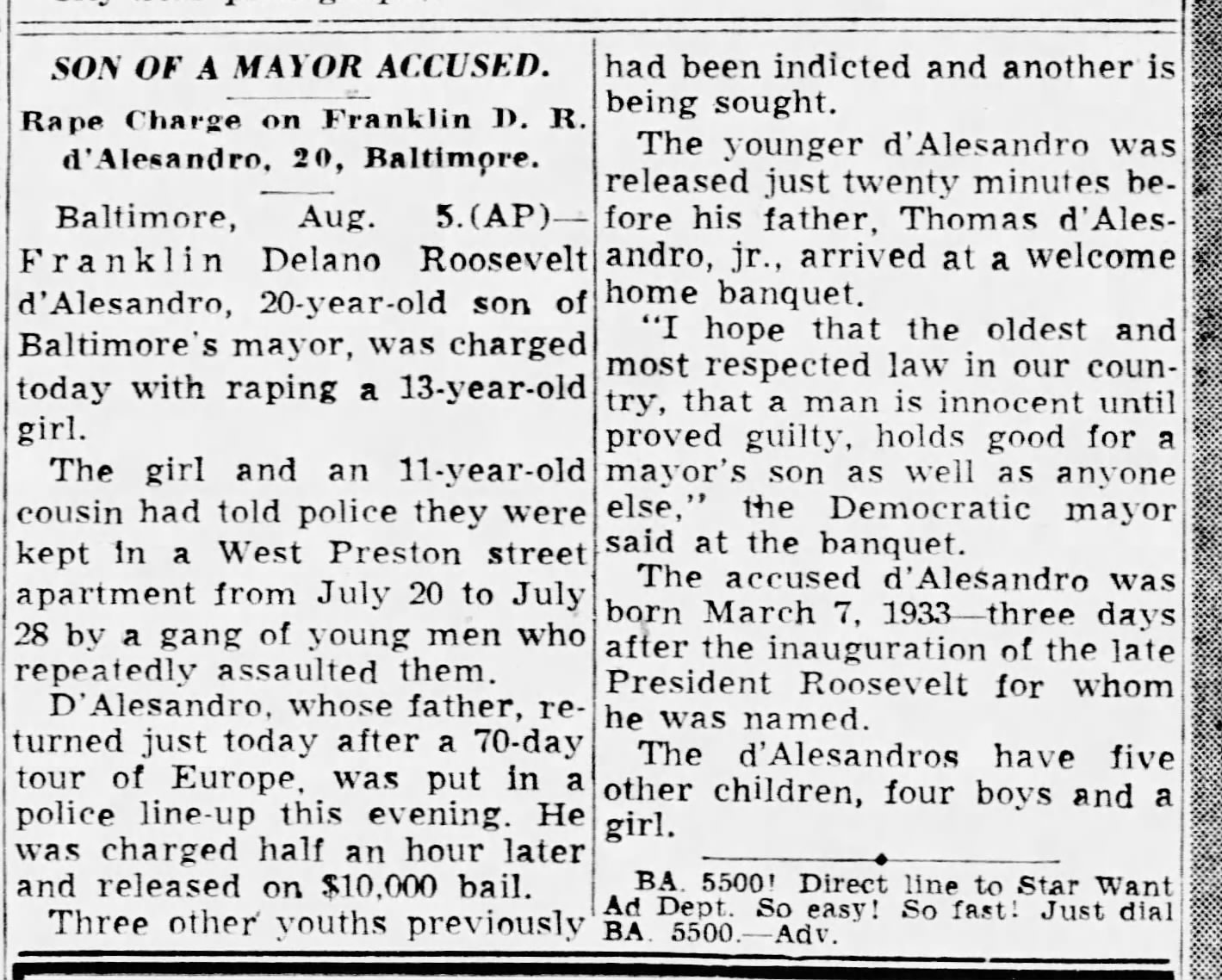

“We loved him and trusted him, and it was never any question,” Pelosi told USA Today’s Susan Page about her brother “Roosie,” or Franklin Delano Roosevelt D’Alesandro, who was charged and then acquitted with a group of other young men–all of whom were convicted except for Pelosi’s brother–of raping two underage girls in the early 1950s.

Pelosi made the comments to Page in an interview for her just-published book, Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power. Page, USA Today’s Washington Bureau Chief, sat for extensive interviews with Pelosi for the book. She also moderated last year’s vice presidential debate between former Vice President Mike Pence and Vice President Kamala Harris.

These revelations are potentially politically explosive for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, they bring to the forefront of political discussion the gruesome details of the allegations against her now-deceased brother yet again—which have not been explored in decades. They were briefly mentioned in a Baltimore Sun obituary for Pelosi’s brother in 2007, but the facts of the case—including the fact that everyone else charged was convicted and the judge’s curious instructions to the jury ahead of their deliberations on the charges against the then-mayor’s son—have not been fleshed out in the modern era politically.

Perhaps more superficially, Pelosi’s comments about the matter also undercut a key Democrat talking point in the MeToo era where powerful men have gone down over allegations against them from women. Democrats have claimed they want to “believe all women.” In fact, when the U.S. Senate confirmed now Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh despite allegations against him, Pelosi issued a statement calling it a “profoundly heart-breaking day for women, girls and families across America.”

“Courageous women risked their safety and well-being to speak truth about this nomination,” Pelosi said about Kavanaugh’s confirmation. “Tens of thousands more joined them to share their own harrowing stories of sexual assault, at great personal risk. Yet, Senate Republicans chose to send a clear message to all women: do not speak out, and if you do – do not expect to be heard, believed or respected.”

But Pelosi makes clear in this new interview for Page’s book that she never once believed the young girls who made accusations against her brother.

Page wrote that Pelosi said “she never doubted her brother’s innocence” and that “she said it was either a politically motivated prosecution aimed at hurting her father or a case of another defendant trying to shift the blame to someone else.” At the time of the rape charges for which Roosie was acquitted, Pelosi’s father was the mayor of Baltimore.

This instance with her brother is not the only time Pelosi has defended men accused of sexual misconduct by women, either. When now former Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) first faced accusations that ultimately forced him to resign from Congress after decades of service, Pelosi defended him and praised his career. According to Business Insider, Pelosi in a Meet The Press interview called Conyers “an icon in our country” who she said has “done a great deal to protect women.” She pushed the matter to the Ethics Committee to handle and refused to call for his resignation.

In the Page book interview, Pelosi called her brother, who passed away at age 73 in 2007, a “beautiful, lovely person” and said his accusers were likely politically motivated. “I thought it was so unfair, because I thought somebody was trying to accuse him of something because they were trying to besmirch my father,” Pelosi told Page.

Pelosi added that given that her father was the first Catholic and first Italian American elected mayor of Baltimore, that “Daddy” was a political target and thinks that is why her brother had to fend off rape charges. More from Page’s book:

Her father was the first Italian American and the first Catholic to be elected mayor, she noted, operating in a “competitive world” of Baltimore politics. “It was like that because of Daddy,” she said. “They’re always trying to take him down.”

Pelosi’s telling of the story is not necessarily the full picture, though. Roosie, her brother, was a part of a group of 14 young men implicated in sexual misconduct toward two girls—aged 11 and 13—and all of the rest of the young men were convicted in the heinous crime. Pelosi’s brother was acquitted, and later was acquitted on charges of perjury related to the central case.

In her book, Page described the incident as a scandal that rocked Pelosi’s father’s political world in 1953 when he arrived on a ship in New York on Aug. 4 of that year.

“Roosie was likely to be arrested the next day on charges of rape,” Page wrote. “He was one of fourteen young men who had been implicated in the sexual assault of two girls, thirteen and eleven years old. Two weeks earlier, the girls, cousins who had run away from their home in East Baltimore, allegedly had gone on an all-night joy ride with four of them, including Roosie. Then the young men paid ten dollars to rent a furnished two-room apartment, where the girls stayed for a week. They were the victims of rape and other ‘perverted practices,’ according to the grand jury indictments. One of the indictments was for an unidentified ‘John Doe’ that one of the girls had heard being called by the name ‘Rudy’ or ‘Rootie.’”

Page continued by noting that Pelosi’s father, then Baltimore Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., grilled Pelosi’s brother on the allegations against him when he returned—and accepted his denial at face value, per court transcripts.

“Roosie returned to Baltimore Tuesday night,” Page wrote. “At midday Wednesday, he and his girlfriend were among the contingent on hand at the Mount Royal train station to welcome home his parents and Little Nancy. The Baltimore & Ohio train pulled in right on time, at 12:38 p.m. From that moment on, Mayor D’Alesandro would be immersed in frantic efforts to defend his son and protect his family. When they arrived at home in Little Italy, he called his son into the master bedroom. ‘He said to me: ‘Tell me the truth. Did you have anything to do with any girls?’ ‘Roosie later testified. ‘And I told him the truth and said ‘no.’’ That was enough for his father and his family.”

The looming charges against Roosie were getting tons of media attention, with reporters “camped out on the street” recording “ the comings and goings of the city’s powerful” from the residence of the mayor. Then at 3:15 p.m., according to Page’s book, Joseph Sherbow, a “prominent former judge” who had just been hired as Pelosi’s brother’s defense attorney, arrived at the house.

That day, he headed down to the police station to stand in a lineup where one of the young girl victims identified him.

“At 5:10 p.m., Roosie walked out of the house in a blue suit and climbed into the car for the short drive downtown, to stand in a lineup at Baltimore police headquarters,” Page wrote. “At the station, the police commander told Roosie to take off his suit jacket and tie; during the alleged crimes, none of the young men had been so formally dressed. His shirtsleeves were rolled up and his collar open when he stood with five other young men in a row against the wall in the third-floor room. The lineup began at 5:30 p.m., the girls behind a screen that shielded them, each in turn. The younger girl identified Roosie as the man she saw through a door in the apartment that was ajar. But she remarked that the man whose nickname she had heard as ‘Rudy’ had seemed taller in the apartment than he did in the lineup. Fifteen minutes later, a police officer filled out the Central Police Station docket with Franklin Delano Roosevelt D’Alesandro’s name and the charges against him. He was booked and fingerprinted; his mug shot was taken. He waited in the police commander’s office while Sherbow hurried to the courthouse to request bail. By 7:15 p.m., Roosie was headed back to Little Italy.”

Only three months later, Roosie—Page wrote—was the only one of the 14 men charged in the case to be acquitted. All other 13 men were convicted. The jury only took 25 minutes to acquit him.

“Three months later, Roosie was acquitted,” Page wrote. “After just twenty-five minutes of deliberation, the jury of twelve men voted unanimously to find him innocent. The young D’Alesandro would be the only one of those charged in the case to win acquittal; the other thirteen were all convicted. During his three-day trial, Roosie denied ever meeting the two young girls. Denied riding in a car with them. Denied taking them to a furnished room to stay for a week. Denied raping the thirteen-year-old. His girlfriend and her parents bolstered his alibi, saying he had eaten dinner and sometimes slept overnight on a couch in their living room during some of the days in question. It was during a crucial week while most of his family were traveling abroad. Young D’Alesandro was a victim of mistaken identity, his lawyer told the jury—referring to him in court as ‘Frank’ rather than ‘Roosie,’ which was so similar to the nickname the girl remembered. [His lawyer] noted that the eleven-year-old girl who picked him out of a lineup had remarked then that he had seemed taller in the apartment. Perhaps to reinforce the case for confusion, Roosie’s three younger brothers showed up each day in court and sat on the front bench with him, all wearing identical blue suits.”

The judge literally even told the jury before they went into deliberations about Pelosi’s brother that he would have—regardless of the fact that these were charges against the mayor’s son—found him not guilty, clearly influencing the jury before their deliberations began. More from Page’s book:

“I have no hesitancy in saying to you that if the case was submitted to me without the aid of jury, I would have no hesitancy in saying not guilty,” the judge told the jury before it began its deliberations. The prominent position of the defendant’s father shouldn’t be a factor, one way or the other, he went on: “It would be infamous and outrageous if this boy were dismissed out of favor. It would be equally infamous and outrageous if he were convicted merely out of prejudice.” When the verdict of “not guilty” was read, Mayor D’Alesandro, who had sat in the courtroom throughout the trial, stood up, wept, and embraced his wife.

Later, when several of the other boys went through their trials which came after Roosie’s trial, their testimony contradicted Roosie’s denials at his own trial. Page writes that Roosie was indicted a second time by the grand jury on perjury at his trial, and then later acquitted on the perjury charges as well.

“Roosie D’Alesandro’s legal troubles weren’t over with his acquittal,” Page wrote. “Trials for three other defendants followed in the next two weeks, also presided over by Judge Smith. All of them were convicted of statutory rape or perverted practices, and all of them implicated D’Alesandro. They hadn’t been witnesses at Roosie’s trial because he had gone first. Since their own trials were pending, their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination had meant they couldn’t be compelled to testify. The judge ordered the state’s attorney to open a perjury investigation. In December, a grand jury indicted Roosie for lying, calling his testimony at his trial ‘willfully and corruptly false.’ Roosie D’Alesandro’s second trial lasted longer than the first. At this point, prosecutors noted, eight other witnesses had given testimony that conflicted with his denials. Those witnesses included two police officers, members of the protective detail at the mayor’s home, who said they had seen Roosie with the other boys on that first, crucial night in question. The jury deliberations lasted longer, too. After more than six hours, they voted to acquit.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.