On the Ides of March 240 years ago in the muddy fields and woods outside Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, the course of the Revolutionary War changed in an epic battle. In the heart of the melee, a six-foot-six, 260-pound giant armed with a massive broadsword battled for freedom.

Following the disastrous American defeats at Charleston and Camden, South Carolina, in 1780, the Revolution tilted in favor of the Crown. The British Southern strategy appeared unstoppable, and even America’s French allies considered pulling the plug. To stem the British tide, Washington sent Nathanael Greene, his most able general, to rehabilitate the army and save the South. Boldly, Greene divided his army. One wing, the Flying Army, commanded by the legendary Daniel Morgan, won a crushing victory at Cowpens, capturing hundreds of British prisoners. General Charles Cornwallis was bent on avenging his losses and, if possible, liberating his imprisoned men. One British officer summed up Cornwallis’s quest to annihilate his foe: “With zeal and with bayonets only it was resolved to follow Greene’s Army to the end of the world.”

Burning their baggage, tents, and even the army’s precious supply of rum, Cornwallis converted his forces into a light corps –hunting Greene through North Carolina’s backcountry as the Americans fled to the Dan River and the perceived safety of Virginia.

Peter Francisco riding with Greene’s army faced unimaginable hardships. Known as the “Giant of the Revolution,” twenty-year-old Francisco was an orphan born in the Azores, a sea captain, left on the docks of City Point, Virginia at the age of five. Locals took in the young boy, who only spoke Portuguese. They tutored him, and he later became a blacksmith. Armed with a musket and a massive broadsword, the hulking Virginian joined a Virginia regiment and battled at Germantown, Brandywine, Fort Mifflin, and at Stony Point, where he suffered a gaping wound across his gut, kept fighting, and helped secure the fort.

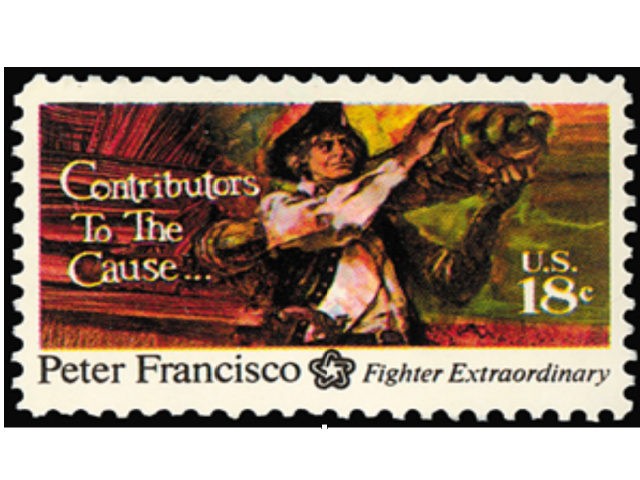

At the battle of Camden, one of the US Army’s most significant defeats, Francisco slew several Redcoats with his six-foot broadsword, and then, according to legend, he single-handedly carried off a cannon from the field. The United States Postal Service commissioned a stamp commemorating the feat even though documentation on the action is limited.

During the race to the Dan, Greene’s army faced one of the most formidable and adaptable armies in the world, determined to exterminate them. Incessant frigid rain and snow transformed roads into a quagmire of muck and filth; as one soldier described it, “Every step being up to our Knees in Mud . . . raining on us all the way.” The barefoot men were soaked to the bone, and some left a trail of bloody footprints. Greene himself noted, “One-half of our number are naked.” Despite the extreme deprivation, the Americans, often starving, marched up to 18 hours a day, skirmishing at places like Cowan’s Ford, North Carolina.

The power of an idea, the concept of freedom, drove unpaid volunteers to march, often barefoot and naked, hundreds of miles. Ultimately, many of these Americans traversed and battled a mind-boggling 4,000 miles over a two-year period. I reveal why this generation sacrificed everything for this cause in a forthcoming book: The Indispensables: Marblehead’s Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the Country, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware. The book is a Band-of-Brothers-style treatment of this unique group of Americans who changed the course of history.

During the race to the Dan, Greene and Washington’s Immortals were always just a whisker ahead of Cornwallis, who was doggedly pursuing the American army. Their flight was part of Greene’s larger strategy of wearing down his opponent through all the marching and skirmishing as they pushed north toward Virginia. These resolute men’s valiant efforts in one of the great retrograde actions in military history led to their salvation on Valentine’s Day 1781 and depleted Cornwallis’s ranks. Weeks later, Greene’s reinforced army re-crossed the Dan to confront Cornwallis’s attenuated army at a small North Carolina town, Guilford Courthouse.

Ill-clothed, poorly-equipped, unpaid, and hungry, the ragged southern Patriot army assembled outside Guilford Courthouse, present-day Greensboro. Cornwallis had been pursuing Greene’s army for months, and he thought he saw the opportunity to strike a mortal blow to the Patriot forces. Greene was ready. He positioned his men in several lines of defense backstopped by the elite troops of the 1st Maryland “Washington’s Immortals.” Designed to bleed the advancing army, the “collapsing box” defense would slowly give way to the enemy while inflicting as many casualties as possible.

In the early morning mist of the 15th, the British advanced. Fierce fighting ensued as the British charged forward, while the Patriot lines fired numerous deadly volleys. The first and second lines of Patriot defense retreated as the British juggernaut continued to close in on Greene’s final defense—the Marylanders.

Central to the fight was an encounter between two of the most decorated and valiant units of the war. On the Patriot side were the Marylanders, the first elite unit in the Continental Army. As Washington’s Immortals chronicles, these trusted soldiers mad,e an epic stand against Cornwallis in Brooklyn, which allowed a large portion of the American army to escape before going on to battle in Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, Stony Point, and Cowpens. At Guilford, they faced off against a British unit known as the 2nd Guards. As the two elite units closed to within yards of each other, the Marylanders’ line erupted with a tremendous volley of fire. “They fired at the same instant, and they appeared so near that the blazes from the muzzles of their guns seemed to meet,” recalled one participant. The Marylanders’ shots had an immediate and deadly impact on the Guards, who “were thrown into confusion by a heavy fire.”

The piercing sound of bugle broke through the din of battle. William Washington’s cavalry and Francisco swooped down upon the Guards, slashing and hacking. “I was wounded in the thigh by a bayonet, from the knee to the socket of the hip, and in the presence of many, [I] was seen to kill two men, besides making other panes [sic] which were doubtless fatal to others.”

Marylander and hero of the battle of Cowpens, John Eager Howard recalled, “The whole were in our power,” and ordered his men to charge with their bayonets. In the carnage, Thomas Carney, an African American Continental, like many of his fellow Marylanders, let out a yell and bayoneted seven of the enemy.

The Guards were about to be destroyed, but Cornwallis fired into the melee with grape and canister from his guns, tearing into the ranks of Patriot and Crown soldiers alike. Greene’s 2nd Maryland Regiment made up mainly of inexperienced levies—not the elite troops of the 1st Maryland—broke in battle. The battle turned, and the American line began to falter.

Having accomplished his mission of badly damaging Cornwallis’s army and causing enormous casualties, Greene wisely decided to leave the field. He left scores of bleeding and dying in his wake. Cornwallis’s commissary general Charles Stedman captured the carnage, “The night was remarkable for its darkness accompanied with rain which fell in torrents. Nearly fifty of the wounded, it is said sinking under their aggravated miseries, expired before the morning. The cries of the wounded and dying, who remained on the field of action during the night exceeded all description. Such a complicated scene of horror and distress, it is hoped, for the sake of humanity, rarely occurs, even in military life.”

Too weak to pursue Greene’s intact army and unable to hold British outposts in North Carolina, Cornwallis moved his battered army to Wilmington, North Carolina, for resupply. After licking his wounds, he fatefully decided to invade Virginia, ultimately ending up at Yorktown and putting his army—and the war’s outcome—at risk. As a result, Greene and the Marylanders marched back into South Carolina. They defeated each British outpost, effectively clearing the state of the British and ultimately bottling up the British in Charleston.

While neither the British nor the Americans realized it at the time, Guilford Courthouse altered the course of the war. It changed both sides’ strategy: it halted a potentially disastrous pending Patriot attack on New York, stopped the British conquest of the Carolinas, and set the stage for a stunning defeat of a British Army at Yorktown.

Wounded during the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and returning alone to Virginia, Francisco encountered a party of British troopers from Banastre Tarleton’s cavalry plundering Amelia County. A British trooper placed his sword under Francisco’s arm and demanded his watch and other property; the giant reportedly “stepped back one pace to the rear, seized his sword by the hilt, cut off a large portion of his skull, and killed him. He had neither sword nor pistol of his own but fought with his adversaries own weapons.” The American hulk drove off the remaining men and “took eight horses and their trappings.”

Decades after the Revolution, Francisco applied for a military pension for his service (many Revolutionary War soldiers died in poverty before Congress authorized pensions for veterans). A bureaucrat denied the claim. Several officers and men who served with the giant then stepped forward and swore under oath, verifying many of his exploits in battle, and the application was finally accepted. The Giant of the Revolution served his final days on Earth as the Sergeant-at-Arms of the Virginia Senate. After his death, four states proclaimed the Ides of March Peter Francisco Day, and his monument in New Bedford, Massachusetts reads: “He Was Truly A One-Man Army.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of twelve books, including The Indispensables, Washington’s Immortals, and The Unknowns. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. Monthly, he hosts The History Happy Hour and interviews American Heroes such as Rangers from WWII to SOG commandos from the secret war in Vietnam see @combathistorian PatrickODonnell.com

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.