Friends in High Finance

Barack Obama’s new memoir, A Promised Land, bills itself as “a riveting, deeply personal account of history in the making—from the president who inspired us to believe in the power of democracy.” And of course, it’s an instant mega best-seller, eagerly bought by blue-dot believers everywhere, fully justifying the 2017 book-deal by which Barack and Michelle Obama jointly sold their reminiscences for $65 million.

So okay, now that Barack Obama is firmly and forever instantiated among the one percent, we might ask: What does A Promised Land have to say about, for instance, income inequality and high-end financialism? This is a particularly pertinent question because much of Obama’s presidency was defined by his relationship with Wall Street, including the bailouts, the cost of which a 2010 estimate put at $14.4 trillion.

As they look back at the Obama years, Americans might ask: Why did the stock market get so high? Why did Manhattan real estate get so expensive? Why did the Democrats get so many large campaign donations? For answers, Americans might look to those bailout trillions because the money had to go somewhere.

In the meantime, from 2007 to 2010, the banks and other lenders foreclosed on an estimated 3.8 million homes.

We can see that this was, indeed, a scandalous situation: many trillions of dollars was sloshed around for the very fatcats who had helped provoke the meltdown, while the lives of millions of ordinary people melted.

Protester sit down in front of a police barricade in front of the Obama administration’s U.S. Department of Justice during a rally against big banks and home foreclosures in Washington, DC, on May 20, 2013. (JIM WATSON/AFP via Getty Images)

So what did President Obama do? Well, first he hired Wall Street-friendly officials, such as Tim Geithner at Treasury and Larry Summers at the National Economic Council, and then he sat passively as his Justice Department did little or nothing about obvious wrongdoing. In the words of iconoclastic leftist journalist Glenn Greenwald:

One of the greatest and most shameful failings of the Obama administration: the lack of even a single arrest or prosecution of any senior Wall Street banker for the systemic fraud that precipitated the 2008 financial crisis.

In his memoir, Obama has little choice but to take up these matters. He writes that while it was “tempting” to view high finance as honeycombed with crooks in need of “Old Testament justice,” that was not possible. He argues:

The trouble was that in the midst of a financial panic, in a modern capitalist economy, it was impossible to isolate good businesses from bad, or administer pain only to the reckless or unscrupulous. Like it or not, everybody and everything was connected.

In other words, Obama is saying, the national and international financial system was too connected—too delicate—for anyone to be prosecuted. The memoir’s obvious filibustering about bringing the law to bear on grifting greedheads moved Harry Siegel of The Daily Beast, in an otherwise mostly admiring book-review, to splutter about his rationalization, “What chickenshit!”

The bailouts might have been justifiable in terms of preventing another 1929-style Depression, and yet they were going to be popular only if they had been accompanied by clawbacks of ill-gotten gains and criminal prosecutions. Such a plan wouldn’t have been so much “Old Testament justice” as simply justice.

Interestingly, Obama seems to have had some second thoughts about his passivity, writing,”I wonder whether I should have been bolder in those early months, willing to exact more economic pain in the short term in pursuit of a permanently altered and more just economic order.”

But Obama’s second-thoughts-ing doesn’t last long. After contemplating in print for a little bit, he concludes that he had it right the first time: “I can’t say I would make different choices.”

The truth is that Obama was a Wall Street-friendly president. He started with bailouts, then moved to free trade deals and a lenient attitude toward financial concentration. So is it a coincidence that Wall Streeters, hedge funders, and wheeler-dealers loom so large in the Democratic Party’s financial support structure? And that financiers mostly paid for the Obama presidential library? Probably not.

Of course, one good way to defend Obama from the criticism that he was a Wall Street tool is to point out that his immediate predecessors were little different: George W. Bush filled his administration with Goldman Sachs executives and other financialist monarchs, as did Bill Clinton. And Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, hired as his Treasury Secretary yet another Goldman Sachs alum, Steven Mnuchin.

The point here is not that Wall Streeters are automatically bad—Mnuchin, for example, has been energetic and effective in dealing with the impact of Covid-19. Instead, the point is that Obama wasn’t so different from the presidents around him; seen from a distance, his administration blends in with most others of his era.

Audacity? What Audacity?

That blending in—the existence of more similarities than differences between his presidency and those of others—is what jumps out of Obama’s tome. Indeed, the book speaks to his instinct simply to get along and go along. A Promised Land is studded with words that speak to the limitations that the author felt as president: words such as “maybe,” “process,” and “still,” as in, High hopes notwithstanding, it was still the case that . . .

Wading through such waffling, it’s hard to remember that one of Obama’s previous books was entitled, The Audacity of Hope.

We can add that another word oft seen is practical, as in “as a matter of practical politics” and “as a practical matter.” And another “p”-word is pattern: “I didn’t like the deal. But in what was becoming a pattern, the alternatives were worse.”

Yet even if Obama’s more ambitious policy goals were often easily thwarted—that’s not practical, Mr. President—Obama himself plays the starring role in his own internalized drama. Indeed, close observers have long noted his abundant use of the word “I,” and this book is in keeping with that solipsistic pattern.

As he writes of himself, he has “a deep self-consciousness. A sensitivity to rejection or looking stupid.” And he adds that sometimes he has “a preference for navel-gazing over action.”

Sometimes, to be sure, this inwardness helps him maintain perspective. For instance, in 2009, when it was announced that he has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, his immediate reaction was “For what?” (In fact, during his first term Obama greatly expanded the Afghanistan war; such a military escalation is surely a first among Peace Prize laureates.)

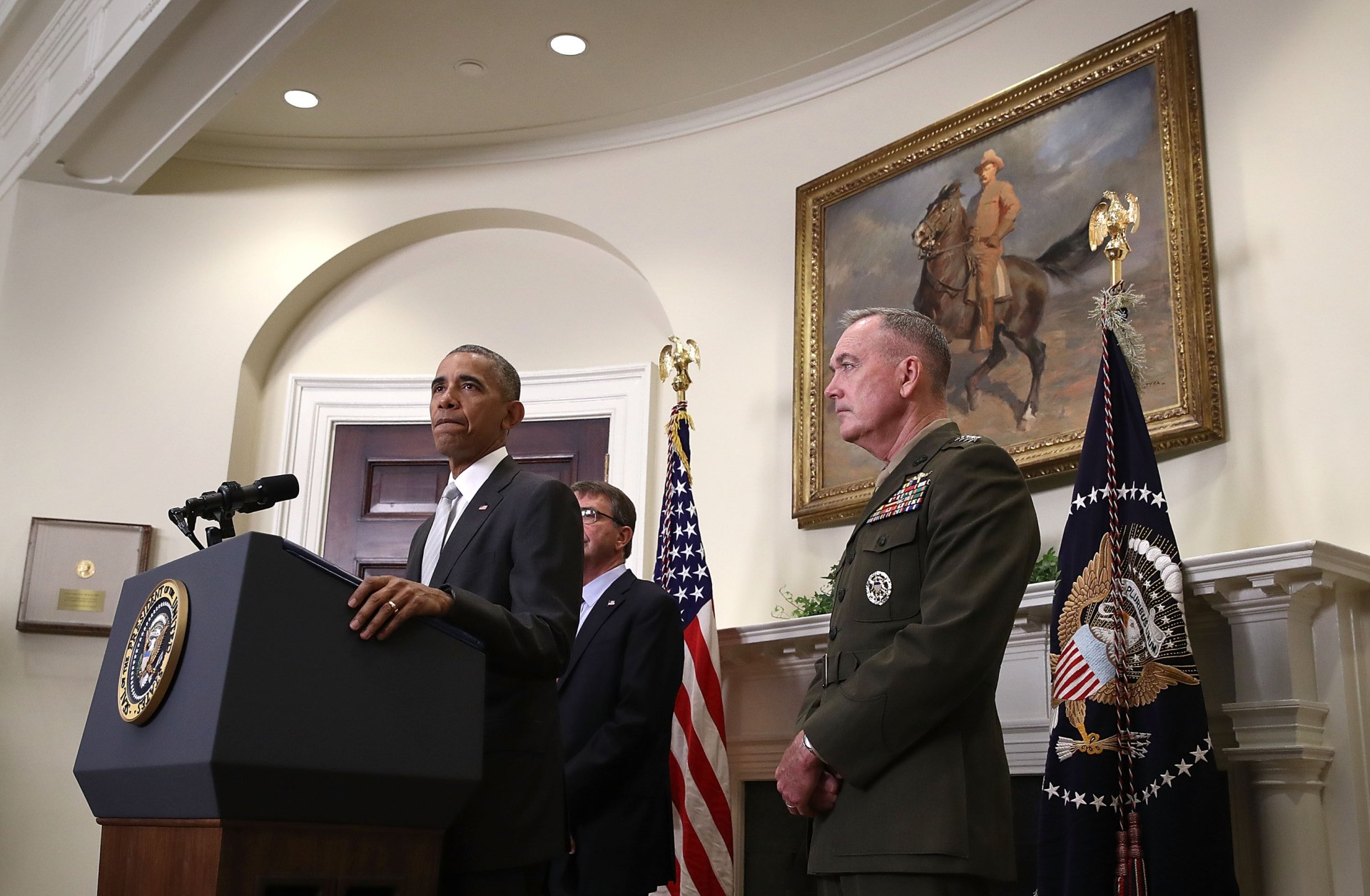

U.S. President Barack Obama, flanked by Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford (R), delivers a statement from the Roosevelt Room at the White House on July 6, 2016, concerning the deployment of more U.S. troops in Afghanistan than he originally planned. (Win McNamee/Getty Images)

In the summarizing words of another reviewer, John F. Harris, writing for Politico, “Obama as a writer makes clear: He spends a lot of time in his own head, and Obama as politician and president did the same.” And as Washington Post reviewer Carlos Lozada explained, A Promised Land “is less a personal memoir than an unusual sort of history, one recounted by the man at the center of it, a man who seems always to be observing himself in action, always wondering if he is guiding the currents or driven by them.”

Yes, Obama’s book is also a history, even as it is curiously truncated. After 700 slogging pages, the book ends in May 2011. The second volume, on sale in a few years, will take us through the remaining time of Obama’s presidency, as well as his post presidency.

Yet still, there’s some modesty here, too. For instance, Obama invites the next generation to “remake the world, and to bring about . . . an America that finally aligns with all that is best in us.” That’s a nice thought, although, of course, it only underscores the point that Obama as president did not “remake the world.” (Some will say, Just as well!)

Thus the author is left to justify his actions by his intentions, as opposed to the results. As reviewer Harris puts it: “[Obama] plainly believes if he can adequately explain himself—how smart he is, how conscientiously he agonized over questions, and with such keen perceptiveness about differing points of view—this will cause people to look sympathetically at the decisions he did make.”

Unfortunately, such keening self-awareness is not the same thing as candor or revelation. For instance, the book gives short-shrift—more like no shrift—to such dubious figures in Obama’s past life as Bill Ayers, Allison Davis, and Tony Rezko.

In addition, the reader does not have to believe the author when he tells us that he was never in the pews of the Trinity United Church of Christ on the Sundays when the Rev. Jeremiah Wright was delivering “God damn America”-type sermons.

Yet at the same time, Obama shows awareness of others. Having padded the book with shout-outs to past aides and advisers, he is less complimentary toward political opponents; he writes, for instance, that Sen. Mitch McConnell “lacked in charisma or interest in policy,” and yet, he continues, the Kentuckian “more than made up for” those lacks through “discipline, shrewdness and shamelessness—all of which he employed in the single-minded and dispassionate pursuit of power.”

And Obama is even less complimentary to Sen. Lindsey Graham, describing him as like the snaky guy in the crime-caper movie “who double-crosses everyone to save his own skin.”

As for his vice president for eight years, Joe Biden, Obama praises him fulsomely, yet adds that he could “get prickly if he thought he wasn’t given his due.” Yes, Biden’s prickliness in the face of a slight could be an interesting dynamic to watch in the coming years. “Middle Class Joe” might never tweet much, but most likely, we’ll have good occasion to see how he reacts toward a perceived insult.

A Fox, Not a Lion

So we are starting to see Obama’s self-portrait of himself as a thoughtful guy—maybe too thoughtful to be an effective president. After all, one might say, a great president is one who can make great change.

It’s often said that politics is the art of the possible, and yet at its most profound, politics is the art of the transformation. One transformative president, of course, was Ronald Reagan. In fact, even Obama recognized the powerful impact of the 40th president; back in 2008, when he allowed, “I think Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not. He put us on a fundamentally different path.”

So we can see that Obama has always been aware of the possibility of transformative change; it’s just not quite his cup of tea. In the White House, Reagan faced plenty of obstacles, too, and yet he found a way to transcend them.

And that’s the irony of Obama: For all his “Yes, we can” rhetoric in 2008, he was content to say, at least to himself, “No, we can’t.”

Yet still, he isn’t the type to blame himself, at least not too much. For instance, he writes of the 2010 midterm elections, when Democrats lost the House and nearly lost the Senate, that the results “didn’t prove that our agenda had been wrong.”

But then he adds, damning himself ever so slightly, “It just proved that—whether for lack of talent, cunning, charm or good fortune—I’d failed to rally the nation, as FDR had once done, behind what I knew to be right.”

Indeed, as Obama seeks to explain away failures, he sometimes leans on arguments about structural racism. There’s no doubt that some Americans disliked him simply because he was black, and yet at the same time, he was elected to national office twice. So yes, it’s true that America has sometimes witnessed “centuries of state-sponsored violence by whites against Black and brown people,” and yet it’s also true that Obama benefited from enormous good will and the hope that he would succeed—and not just from Democrats. In 2008, after all, he carried Mike Pence’s Indiana.

Meanwhile, unsurprisingly, Obama’s discussion of race includes swipes at Trump. The memoirist argues that no small part of Trump’s appeal in 2016 was to “millions of Americans spooked by a Black man in the White House,” adding, “He promised an elixir for their racial anxiety.” We can assume that in the forthcoming volume two, Obama will stick it to Trump, good and hard.

U.S. President Barack Obama meets with President-elect Donald Trump to update him on transition planning in the Oval Office at the White House on November 10, 2016. (JIM WATSON/AFP via Getty Images)

Yet as we think about the 44th and 45th presidents, we might be reminded of the typology set forth five hundred years ago by the Italian political philosopher Machiavelli. The political world, he asserted, was divided between two types: lions and foxes. As he explained in Book XVIII of The Prince, each creature had its strength and weakness:

The lion cannot defend himself against snares and the fox cannot defend himself against wolves. Therefore, it is necessary to be a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify the wolves.

Machiavelli’s idea was that the two metaphorical critters—in reality, of course, two types of people—would be best if they could work together. That is, the fox would identify the traps, and the lion would chase away other predators.

And yet by themselves, foxes and lions were each vulnerable: The fox lacked strength and courage, while the lion lacked the wisdom to steer clear of traps.

In our time, we can update Machiavelli: Obama is fox-like. That is, he saw the dangers, and so he slinked away from them. Yes, he was audacious enough to run for president as just a first-term senator, but once in office, he was sly enough to put his feet down carefully, thus avoiding traps.

As a result, Obama stayed in the White House for the maximum of eight years, and now, in active retirement, he is living prosperously ever after. And A Promised Land helps to show us how he went from a pot-smoking adolescence in Hawaii to life on Easy Street—where maybe he still sometimes sneaks a (tobacco) cigarette. The life of a fox might be long, and yet it most likely won’t be consequential. The ability to avoid traps is not the test of greatness.

Oh, and what about Trump? He is obviously a lion: In the White House, he has made change, that’s for sure, and he has fallen into traps—that, too, is for sure. Can he survive 2020 to roar again? We’ll have to see.

In the meantime, though, Obama, the never-trapped fox, is working on his next best-seller. And it, too, is sure to be full of cautions, meditations, and ruminations about avoiding traps.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.