Democratic nominee Joe Biden took great pains during his debate with President Donald Trump to paint his Republican opponent as racially insensitive and politically divisive.

The former vice president argued that the recent wave of protests and riots roiling America’s cities since the death of George Floyd in police custody has exposed Trump’s weakness as a leader. Biden, in particular, claimed that the president has done nothing in the last four years to address racial injustice or heal political divides.

“This is a president who uses everything as a dog whistle to try to generate racist hatred, racist division,” Biden said, adding that “this man has done virtually nothing for black Americans.”

Biden’s critiques struck some as odd given the former vice president’s long tenure in public office and his own problematic record on racial issues and his past racially insensitive comments. The following is an extensive, but not exhaustive, look into the Democratic nominee’s past stances and comments.

1. As recently as June of 2019, Biden praised the “civility” of the segregationist senators he worked with in Congress to pass anti-busing legislation.

In June of 2019, the former vice president engendered criticism after seeming to praise the “civility” of two arch segregationists during a high-dollar fundraiser at the Carlyle Hotel in New York City. During the event, Biden told the audience assembled it was vital the next president “be able to reach consensus under our system.” To explain why he was the best candidate in that regard, the former vice president fondly cited his history of working with two of the Senate’s arch segregationists, the late-Sens. James Eastland (D-MS) and Herman Talmadge (D-GA).

“I was in a caucus with James O. Eastland,” Biden said with an attempted Southern drawl. “He never called me boy, he always called me son.”

“Well guess what?” the former vice president continued. “At least there was some civility. We got things done. We didn’t agree on much of anything. We got things done. We got it finished. But today you look at the other side and you’re the enemy. Not the opposition, the enemy. We don’t talk to each other anymore.”

The comments provoked outrage because of the reputations that Eastland and Talmadge forged during their decades in public office.

Eastland, in particular, was known as the “voice of the white South” for his stringent opposition to civil rights and integration. The New York Times wrote in Eastland’s obituary that “he often appeared in Mississippi courthouse squares, promising the crowds that if elected he would stop blacks and whites from eating together in Washington. He often spoke of blacks as ‘an inferior race.’”

Talmadge was also a fierce opponent of integration. Before being elected to the Senate in 1957, he served as the governor of Georgia, where his tenure overlapped with the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down segregation in public schools in Brown v. Board of Education. At the time of the ruling, Talmadge promised to do everything in his power to protect the “separation of the races.”

Biden, who joined the Senate in 1972, missed most of the early battles on school integration. He did, however, arrive just as busing to achieve school desegregation was coming to the forefront. Despite opposition from more liberal elements in the Democratic Party, especially the late-Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), Biden ended up leading the charge on the issue. Eastland, as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was a prominent ally in the fight against busing, according to the Delaware News Journal.

Letters exchanged between Biden and Eastland during those early years indicate the former vice president courted the pro-segregationist judiciary chairman to help pass his anti-busing measures.

“I want you to know that I very much appreciate your help during this week’s Committee meeting in attempting to bring my antibusing legislation to a vote,” Biden wrote in one letter dated from June 1977.

The former vice president’s praise last year of his two late segregationist Senate colleagues proved controversial, even among Democrats, with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) claiming that the former vice president had proved himself “woefully ignorant” of the “black American experience.”

Although such criticism forced Biden to apologize for giving the “impression” of praising segregationists, the former vice president has continued invoking senatorial colleagues who opposed civil rights. In February of this year, during the tenth Democratic presidential primary debate in South Carolina, Biden fondly recalled his friendship with the late Sen. Fritz Hollings (D-SC).

“Look, a guy who was a friend of mine down here, Fritz Hollings, used to say, ‘Don’t listen to what a man or woman say they’ll do, look at what they’ve done,’” the former vice president said, while criticizing his primary rivals.

As Breitbart News has previously reported, Hollings, who passed away last year, was a longtime fixture in South Carolina politics, serving first as the state’s governor and later as a United States senator. For much of his early career, Hollings was an opponent of integration, even running for the governorship on a platform of opposing school desegregation in 1959. Hollings kept that stance for the early portion of his term, but eventually changed course and supported integration.

In the Senate, Hollings cut a moderate-to-liberal profile by championing a national hunger policy and working to rein in the deficit. During his congressional tenure, Hollings’ views on race evolved, as exhibited by his endorsement of Jesse Jackson in the 1988 presidential race. The topic, however, continued to haunt the reformer segregationist as was evidenced in 1993 when Hollings stirred controversy by claiming that African diplomats only attended international conferences so they could get a “good square meal” rather than “eating each other.”

2. Biden praised the notorious segregationist politician George Wallace, boasted about how Wallace once honored him with an award in 1973, and told a Southern audience in 1987 that “we [Delawareans] were on the South’s side in the Civil War.”

Senatorial colleagues were not the only segregationists that Biden has praised throughout his years in public office. One individual, in particular, that Biden praised repeatedly throughout his early congressional career was the late Alabama governor George Wallace.

“I think the Democratic Party could stand a liberal George Wallace — someone who’s not afraid to stand up and offend people, someone who wouldn’t pander but would say what the American people know in their gut is right,” Biden told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1975 when discussing why liberals should not “apologize for locking up criminals.”

At the time, Biden was a young-first term senator from Delaware who was developing a reputation for bucking his party, most notedly on the contentious issue of busing to desegregate public schools. Notwithstanding the antiquated racial attitudes of that time, Biden’s comments about Wallace were viewed as controversial even by the standards of the 1970s.

Wallace, who was governor of Alabama in the mid-1960s and then again throughout most of the 1970s, stood out in the national psyche for his stringent opposition to integration, even going as far to declare “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” in his 1963 inaugural address. The image was reinforced only months later when Wallace faced down federal law enforcement officers at the University of Alabama while attempting to block integration efforts by then-President John F. Kennedy.

By the time Biden invoked him to the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1975, Wallace was trying to rehabilitate his image by making inroads with Alabama’s black community. Even though he succeeded in that effort by some measure, Wallace remained a vehement proponent of states’ rights, especially when it came to busing and crime—two issues that defined Biden’s early political career.

The political and ideological similarities between the two men have even been acknowledged by Biden on occasion.

In 1975, during an interview with National Public Radio about his support for a constitutional amendment to stop busing, Biden suggested liberals only favored the practice because it was opposed by “racists” like Wallace.

“I think that part of the reason why much of this has not developed, much of the change has not developed, is because it has been an issue that has been in the hands of the racist,” Biden told NPR. “We liberals have out-of-hand rejected it because, if George Wallace is for it, it must be bad.”

“And so we haven’t really looked at it,” he continued. “Now there’s a confluence of streams. There is academic ferment against it — not majority, but academic ferment against it. There are young blacks and young white leaders against it.”

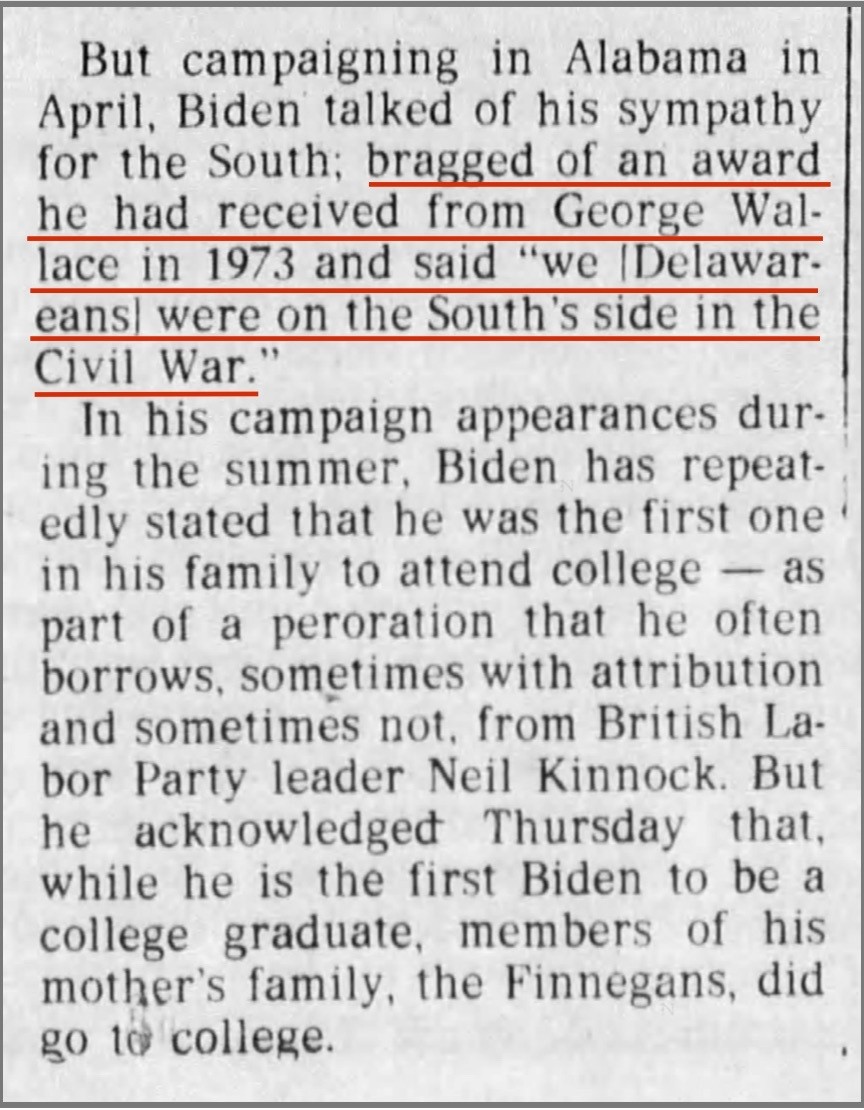

News clipping from an article titled “Presidential hopeful Biden faces an image problem” in The Philadelphia Inquirer on September 20, 1987, page 79

The former vice president similarly invoked Wallace during a 1981 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing to explain why he and countless others supported tough-on-crime initiatives like the death penalty.

“Sometimes even George Wallace is right about some things,” Biden told the committee before claiming Americans supported the death penalty because the government did “not have the slightest idea how to rehabilitate” criminals.

Such instances in which Biden mentioned Wallace only grew through the 1980s, becoming more commonplace in the lead-up to his first presidential run in 1988. Back then, the South was still nominally Democratic but had voted overwhelmingly for President Ronald Reagan in 1980 and 1984. Biden appeared to believe his youth, moderate record, and stance on busing presented the best opportunity to bring Southern whites back into the Democratic camp.

As he traveled the South in 1986 and 1987 to build support for his first White House bid, Biden not only downplayed his support for civil rights, but also made frequent references to Wallace. In April 1987, Biden even reportedly tried to court an Alabama audience by boasting about how Wallace had honored him with an award.

“Biden talked of his sympathy for the South; bragged of an award he had received from George Wallace in 1973 and said “we [Delawareans] were on the South’s side in the Civil War,” as reported by the Inquirer on September 20, 1987. (Although Delaware was a slave-holding border state during the Civil War, it fought on the Union side.)

Apart from openly touting “his sympathy for the South” and the accolade bestowed by Wallace, Biden also bragged that the Alabama governor heaped praise on his capabilities as a politician.

“Sen. Joseph Biden of Delaware … tells Southerners that the lower half of his state is culturally part of Dixie,” the Detroit Free Press reported in May 1987. “He reminds them that former Alabama Gov. George Wallace praised him as one of the outstanding young politicians of America.”

3. Biden opposed busing in the 1970s and expressed fears that it would lead to a “racial jungle.”

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Biden was seen as one of the Senate’s leading opponents of busing to desegregate public schools. The issue was particularly volatile for his constituents in Delaware, especially in the state’s largest city, Wilmington.

As a first-term senator in 1977, Biden raised concerns during a Senate committee hearing on busing that the practice would lead to a “racial jungle” with tensions pushed to their breaking point. At the time, Biden was facing tough reelection prospects.

“Unless we do something about this, my children are going to grow up in a jungle, the jungle being a racial jungle with tensions having built so high that it is going to explode at some point,” Biden said shortly after making a plea for “orderly integration.”

It is unclear exactly which legislation Biden’s remarks were meant to address, as there were many busing proposals floating around in 1977. Despite the background remaining murky, Biden’s remarks at the hearing are similar to those he expressed during an interview with a local Delaware newspaper in 1975 while discussing the issue of busing.

“The real problem with busing,” Biden told the paper, after lambasting busing as an “asinine concept,” was that “you take people who aren’t racist, people who are good citizens, who believe in equal education and opportunity, and you stunt their children’s intellectual growth by busing them to an inferior school … and you’re going to fill them with hatred.”

“The unsavory part about this is when I come out against busing, as I have all along, I don’t want to be mixed up with a George Wallace,” he added.

4. Biden voted to protect the tax-exempt status of private segregated schools.

After being re-elected to his second term in 1978, Biden voted the following year against revoking a legislative provision that prevented the Internal Revenue Service from rescinding the tax-exempt status of private segregated academies. Such schools were founded in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision to prevent the integration of educational institutions.

At the time, Biden’s vote put him at odds with then-President Jimmy Carter and such vaulted liberal institutions as the American Civil Liberties Union.

5. Biden told black radio host Charlamagne tha God, “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t black.”

In May, while appearing on the Breakfast Club, a popular New York City-based radio show, Biden asserted that any voter unsure whether to back him or President Donald Trump this November “ain’t black.”

“If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t black,” the former vice president told one of the show’s black hosts, Charlamagne tha God.

The comments elicited immediate rebuke, including from Charlamagne. In response, Biden’s campaign attempted to playoff the awkward moment, with the vice president, himself, claiming he was being a “wise guy.”

6. Biden told the Asian and Latino Coalition of Des Moines that “poor kids are just as bright and just as talented as white kids.”

During a town hall in August 2019 with the Asian and Latino Coalition of Des Moines, Iowa, Biden elicited controversy by claiming that “poor kids are just as bright and … talented as white kids.” The former vice president, in particular, made the comments while discussing his support for expanding educational opportunities and school funding.

“We should challenge students [with] advanced placement programs in these schools,” Biden said at the time. “We have this notion that somehow if you’re poor you cannot do it, poor kids are just as bright and just as talented as white kids.”

The former vice president quickly attempted to clarify his remarks by adding “wealthy kids, black kids, Asian kids” to the end of his previous sentence.

The comments raised eyebrows forcing Biden’s campaign to issue a statement saying that the former vice president “misspoke.”

7. While delivering remarks before a black audience in Delaware, Biden launched into a meandering story about a gang leader named Corn Pop and claimed that he “learned about roaches” while working at a community pool in a black neighborhood.

In 2017, shortly after leaving the White House Biden delivered a bizarre speech before an audience in Wilmington, Delaware, at the renaming of a community pool in his honor. The event, though, quickly took a strange turn when Biden, flanked by black children from the local community, decided to recount a nearly violent altercation he had with a local gang leader named Corn Pop while working as the only white lifeguard at this pool during his teenage years.

“Corn Pop was a bad dude, and he ran a bunch of bad boys. Back in those days, to show how things have changed … if you used pomade in your hair, you had to wear a bathing cap,” Biden said. “He was up on the board and wouldn’t listen to me, so I said, ‘Hey, Esther, you, off the board or I’ll come up and drag you off.’”

Corn Pop, according to the former vice president, did not take kindly to being called “Esther” — an “emasculating” reference to the 1950s swimmer Esther Williams, as the Washington Post noted — and promised to “meet” him outside. Biden told the audience he realized that he had to take the threat seriously when he purportedly saw the gang leader waiting around for him with three other guys carrying straight razors.

According to the former vice president’s recollection, he walked outside with a “six-foot chain” and threatened to “wrap [the] chain around” Corn Pop’s head, before apologizing.

“I looked at him, but I was smart then,” Biden said, adding that he told Corn Pop, “’First of all, when I tell you to get off the board, you get off the board, and I’ll kick you out again, but I shouldn’t have called you Esther Williams.’ I apologize for that. … I apologize for what I said.”

Biden’s anecdote about Corn Pop was not the only part of the speech that drew attention. In an earlier portion of his remarks, the former vice president raised eyebrows when he described what he learned that summer while working as the only white lifeguard at a community pool in a black neighborhood.

“By the way, you know, I sit on the stand, and it get[s] hot,” Biden said. “I got a lot, I got hairy legs that turn blonde in the sun, and the kids used to come up and reach in the pool and rub my leg down so it was straight and then watch the hair come back up again. They’d look at it.”

“So I learned about roaches, I learned about kids jumping on my lap,” the former vice president added. “And I loved kids jumping on my lap.”

Biden’s inexplicable reference to “roaches,” alongside the broader story about Corn Pop, confounded many. Without proper explanation, more than a few were left to speculate the use of the term was an allusion to the racial and economic makeup of the community frequenting the pool. Some, like the prominent conservative activist and commentator Larry Elder, went further suggesting that Biden was calling the children “jumping on my lap” roaches.

8. In 2008, Biden referred to then presidential candidate Barack Obama as “the first sort of mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean.”

Before Biden was tapped by President Barack Obama for the number two slot on the 2008 Democratic ticket, the two men’s relationship nearly went off the rails over a racial gaffe. In February 2007 as Biden was preparing to launch his own White House bid, the then-senator from Delaware caused a flare-up while discussing his potential rivals for the Democratic nomination. Although, Biden spent a great deal of time evaluating his chances against the likes of then-Sen. Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and ex-Sen. John Edwards (D-NC), his remarks about the freshman senator from Illinois drew the most scrutiny.

“I mean, you’ve got the first sort of mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy. I mean, that’s a story-book, man,” Biden said when discussing Obama.

9. In 2006, Biden told C-SPAN, “You cannot go to a 7-Eleven or a Dunkin’ Donuts unless you have a slight Indian accent.”

In 2006, when first considering a second run for the presidency, Biden appeared on C-SPAN’s “Road to the White House” to discuss his deliberations. Biden told the program that one of his strengths as a candidate would be the broad base of support he’s received from immigrants in his home state of Delaware, especially Indian-Americans.

“I’ve had a great relationship. In Delaware, the largest growth in population is Indian-Americans moving from India. You cannot go to a 7-Eleven or a Dunkin’ Donuts unless you have a slight Indian accent,” Biden said. “I’m not joking.”

At the time, the comments were widely lambasted by members of the Indian-American community. In response, Biden’s then-Senate office tried to explain the gaffe, claiming he was only commenting about how positive it was that Indian-American “middle-class families are moving into Delaware and purchasing family-run small businesses.” That effort, however, was undercut by a subsequent appearance the senator made on CNN in which he defended his comments by suggesting that he would have said the same thing “40-years ago about walking into a delicatessen and saying an ‘Italian accent.'”

10. Biden falsely claimed to have “marched” in the civil rights movement.

During his run for the 1988 Democratic nomination, Biden inflated his record of activism in the civil rights movement. Biden, in particular, repeatedly claimed to have “marched” in the civil rights movement when presenting himself to audiences as a candidate for generational change.

“When I marched in the civil rights movement, I did not march with a 12-point program,” Biden told a group of supporters in 1987. “I marched with tens of thousands of others to change attitudes, and we changed attitudes.”

In reality, Biden had never marched during the civil rights movement, according to Matt Flegenheimer of the New York Times.

“More than once, advisers had gently reminded Mr. Biden of the problem with this formulation: He had not actually marched during the civil rights movement,” wrote Flegenheimer. “And more than once, Mr. Biden assured them he understood — and kept telling the story anyway.”

The exaggeration, along with Biden’s propensity for plagiarism, would eventually force him to abandon his 1988 presidential bid before a single vote was cast.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.