The term “peaceful protest” has been thoroughly degraded in recent weeks: first, by “protesters” who have attacked people and property; second, by journalists who called the riots “mostly peaceful”; third, by celebrities who bailed out “mostly peaceful” rioters; and finally by politicians like Joe Biden, who attacked law enforcement for standing up to the rioters.

The would-be president claimed that Department of Homeland Security officers had been “brutally attacking peaceful protesters”in Portland — “peaceful protesters” who have attacked a federal courthouse, vandalized it, and attempted to set fire to it; “peaceful protesters” who have pelted local police with rocks and bottles, night after night, week after week.

As a society, we have lost touch with what the idea of “peaceful protest” is. This is a very dangerous deficiency, because it means our political future could become more and more violent and unstable — regardless of who wins the 2020 election.

So let’s return to basics.

The right to protest is guaranteed by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech … or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” Though the text only binds “Congress,” the Supreme Court has determined that the First Amendment also applies to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. It is universal.

The key word is “peaceably.” Violent protest is not protected by the First Amendment.

More generally, the courts have ruled that the right to protest is not unlimited. There are “time, place, and manner” restrictions that the government can place on public demonstrations to guarantee public safety and to make sure that the rights of other people are equally protected. As long as the government does not favor (or oppose) the content of that speech, such restrictions are lawful.

To qualify as a “peaceful protest,” a demonstration must not only be non-violent, but it must also be permitted by the government. And the government cannot deny permission — what is often called “prior restraint” — based on content. Anything can be said, or expressed, at a protest as long as it is not an imminent incitement to violence or lawlessness.

That covers what is lawful, and constitutional (and the Portland riots would not qualify). How about what is effective?

Last week saw the passing of Rep. John Lewis (D-GA), one of the foremost civil rights leaders of the 1960s. He is best known for being beaten by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, during a protest march in 1965. It was a significant event because it shocked the nation: Lewis and his fellow demonstrators were not violent at all, and police had attacked them without any provocation whatsoever. The protest was unlawful, but should have been allowed.

Lewis had perfected the tactic of non-violent resistance that was celebrated by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. And Dr. King, in turn, had been inspired by the methods of Mahatma Gandhi, who developed the doctrine of non-violent resistance — first in South Africa, where he led protests against discriminatory laws targeting Indian immigrants, and then in India itself, where he led protests against British colonial rule and paved the way for independence before being assassinated.

Gandhi’s doctrine was based on an idea called Satyagraha, loosely translated as “soul force.” The purpose of non-violent resistance, Gandhi taught, was to appeal to the common humanity of the individual human beings on the other side. If protesters believed fervently enough in their cause to expose themselves to physical danger, but not to pose any danger to those they were protesting against, they would awaken a sense of empathy among their opponents and the world at large.

The tactic could not work everywhere, though Gandhi argued that it could, often to the point of absurdity. (His suggestion for the Jews of Europe was that they should protest Nazism by allowing themselves to be killed.) In a political system that denies the right to protest under even reasonable circumstances, and censors media coverage of protests, such as apartheid South Africa, violence may be justified.

Dr. King understood that the United States was not such a society. The Democrats of the Jim Crow South might suppress protest, but television ensured that the rest of the nation would see that, and recoil.

The civil rights movement was effective because the tactic of non-violence, adapted from Gandhi and applied by King and Lewis, evoked the empathy of observers.

Moreover, Dr. King also used the common language of Christianity to challenge his countrymen to live up to the ideals of their Constitution — and their Bible.

Today’s protests have abandoned the tradition of Dr. King and embraced the ideas of Saul Alinsky, for whom chaos was the goal. (They have even vandalized a statue of Gandhi.)

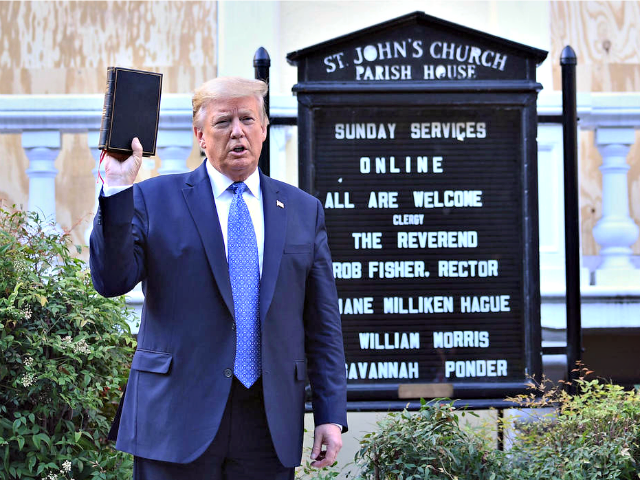

Tragically, President Barack Obama, who could have been a figure of reconciliation as the first black president, embraced the lawlessness of the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 and the Black Lives Matter riots in 2014. And when President Donald Trump holds up a Bible, reminding a divided nation of its common heritage, the media mock him.

Biden, who likes to exaggerate his participation in the civil rights movement, has forgotten its basic tactics and principles. He is mirroring the media, who have encouraged violent protest — partly for ratings, partly because they, too, are radicals.

Other Democrats misquote Dr. King as if he approved of riots. He did not.

If we abandon Dr. King’s legacy, if we call riots “peaceful protest,” we will stop listening to one another, and settle our differences violently.

It has already begun.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). His new book, RED NOVEMBER, tells the story of the 2020 Democratic presidential primary from a conservative perspective. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.