The Navy on Thursday fired the commander of the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, Navy Capt. Brett Crozier, after his memo pleading with leaders to get sailors off the infected ship leaked to media.

“Capt. Brett Crozier was relieved of his command by carrier strike group commander Adm. Stuart Baker. Executive Officer Capt. Dan Keeler has assumed command temporarily until such time as Rear Adm.-Select Carlos Sardiello arrives in Guam to assume command,” Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly said at a Pentagon briefing.

Sardiello is a former commanding officer of the ship, and he is “very well-acquainted” with the ship, many of its crew, and the operations and capabilities of the ship, Modly added.

“He is the best person right now to take command under these unusual circumstances,” he said.

Crozier’s firing came two days after a memo he wrote to the strike group commander was leaked to the San Francisco Chronicle, in which he begged his commanders to let sailors off the ship because they could not abide by Centers for Disease Control and Navy guidelines to social distance during a coronavirus outbreak.

The Chronicle report said more than 150 sailors from the ship were infected, but on Wednesday, Navy officials said it was below 100 at the time and none who have tested positive for the coronavirus have been hospitalized.

Navy officials on Wednesday expressed disappointment that the memo was leaked and said it caused alarm among families and made the jobs of those assigned to communicate with families more difficult.

“I can assure you that no one cares more about their safety and welfare,” Modly said on Thursday. He said his own son is serving active-duty in South Korea, which was one of the first nations to have a “significant spike” of coronavirus cases.

“I understand both as a parent and a veteran how critical our support lines are for the health and wellbeing of our people,” he said. “Especially now in the midst of this global pandemic.”

He said there was a “larger strategic context — one full of national security imperatives of which all of our commanders must all be aware of today. While we may not be at war in the traditional sense, neither are we truly at peace.”

“Authoritarian regimes are on the rise, many nations are reaching in many ways to reduce our capacity to accomplish our own strategic national goals. This is actively happening everyday,” Modly said, referring to “capable global strategic challengers” — a likely reference to China and other near-peer adversaries. He continued:

A more agile and a more resilient mentality is necessary up and down the chain of command. Perhaps more so now than in the recent past, we require our commanders with judgment, maturity, and leadership composure under pressure to understand the ramifications of the reactions under that larger dynamic strategic context.

We all understand and cherish our strategic responsibilities and frankly our love for all of our people in uniform. But to allow those emotions to color our judgment when communicating our current operational picture can at best create unnecessary confusion, and at worst provide an incomplete picture of American combat readiness to our adversaries.

When the commanding officer of the U.S. Teddy Roosevelt decided to write his letter on the 30th of March, 2020, it outlined his concerns for his crew amidst the COVID-19 outbreak. The Department of the Navy already mobilized significant resources for days in response to this previous requests.

On the same day marked on his letter, my chief of staff called the CO directly, at my direction, to ensure he had all the resources necessary for the health and safety of his crew. The CO told my chief of staff that he was receiving those resources, and he was aware of the Navy’s response, only asking that he wish the crew could be evacuated faster.

My chief of staff ensured that the CO knew that he had an open line to me anytime for him to call. He even called the CO a day later to follow up and at no time did the CO relay the various levels of alarm that I along with the rest of the world learn from his letter when it was published by the CO’s hometown newspaper two days later.

He said once he read the letter, he immediately called Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael Gilday and the commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet Adm. J.C. Aquilino. Gilday had just read the letter that day, and Aquilino had received the letter the day before.

Modly said that Crozier’s boss, Baker, sleeps right down the hall from him on the carrier. Despite this, Crozier sent Baker the letter via nonsecure unclassified email, even though the ship possesses some of the most sophisticated communications equipment in the fleet, Modly said.

“It wasn’t just sent up the chain of command, it was sent and copied to a broad array of other people. It was sent outside the chain of command,” he said.

He said that, at the same time, the Navy was “fully responding.” He said Crozier’s actions made his sailors, their families, and the public believe that his letter was the only reason help from the Navy was forthcoming, “which was hardly the case.”

“Command is a sacred trust that must be continually earned both from Sailors and Marines they want to lead, and from the institution that grants that special and honored privilege,” he said.

He said after speaking to all relevant leaders, he could reach no other conclusion but that Crozier had allowed the complexity of the challenge of the coronavirus breakout on the ship to “overwhelm his ability to act professionally, when acting professionally is what we needed at the time.”

“We do and we should expect more from the commanding officers of our aircraft carriers,” he said. “I did not come to this decision lightly.”

He said he has no doubt that Crozier did what he thought was in the best interest of the safety and wellbeing of his crew. Unfortunately, it did the opposite. It unnecessarily raised alarms with the families of our sailors and our Marines with no plans to address those concerns. It raised concerns about the operational capabilities and operational securities of the ship that could have emboldened our adversaries to seek advantage. Modly went on to say:

And it undermined the chain of command who had been moving and adjusting as rapidly as possible to give him the help he needed. For these reasons, I lost confidence in his ability to continue to lead that warship as it fights through this virus to get a crew healthy and so that it continued to meet its national security requirements.

In my judgement, relieving him of command was in the best interest of the United States Navy and the nation in this time when the nation needs the Navy to be strong and confident in the face of adversity. The responsibility for this decision rests with me.

He called Crozier an “honorable man” who has dedicated himself to a “lifetime of incredible service to the nation.”

He said the vice CNO would conduct an investigation into what contributed to the breakdown in the chain of command.

“I have no indication there is a broader problem in this regard, but we have an obligation to calmly and evenly investigate it nonetheless,” he said.

Modly said the decision was not one of “retribution” for raising concerns, but because of the way he did so.

He said he had no doubt that Crozier loved his crew, but that the world needs to know that the ship is courageous, “undaunted and unstoppable.”

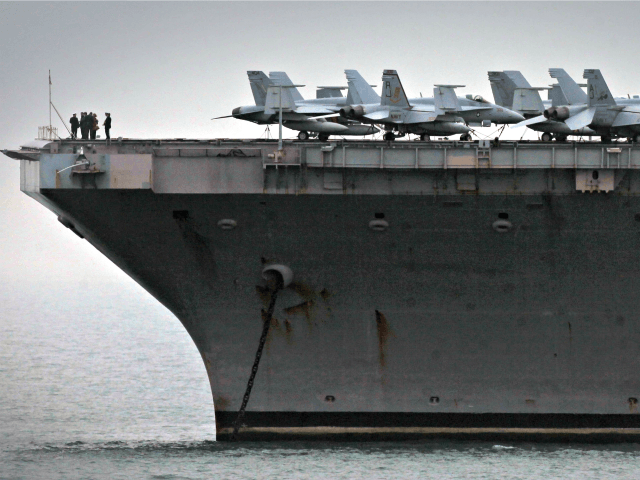

“The nations and the bad actors around the world who wish us harm should understand that the ‘Big Stick’ is in the neighborhood and the crew is standing the watch.”

Modly said he had no communication with the White House before his decision, although he said he spoke with Defense Secretary Mark Esper, who told him he would support whatever Modly decided to do.

Follow Breitbart News’s Kristina Wong on Twitter or on Facebook.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.