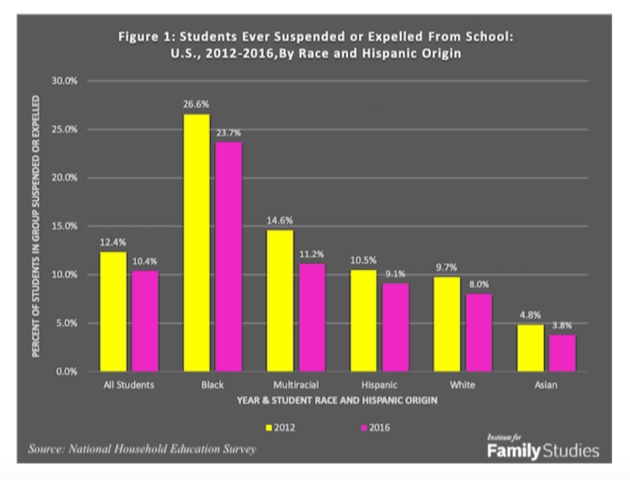

A new study affirms what many public policy analysts say is intuitive — that unstable family structure, including chaotic households and single-parent homes, is a primary factor in racial disparities in school behavior and suspensions.

The study, conducted by senior fellows Nicholas Zill and W. Bradford Wilcox at the Institute for Family Studies, asserts education policymakers “must recognize that social and psychological problems in youth may manifest themselves at school but have their origins in family situations over which the school has little or no control.”

The authors find in their new analysis of the National Household Education Survey (NHES) that, in 2016, about 24 percent of black elementary and high school students had been suspended at least once, while eight percent of white students and only four percent of Asian students had the same experience.

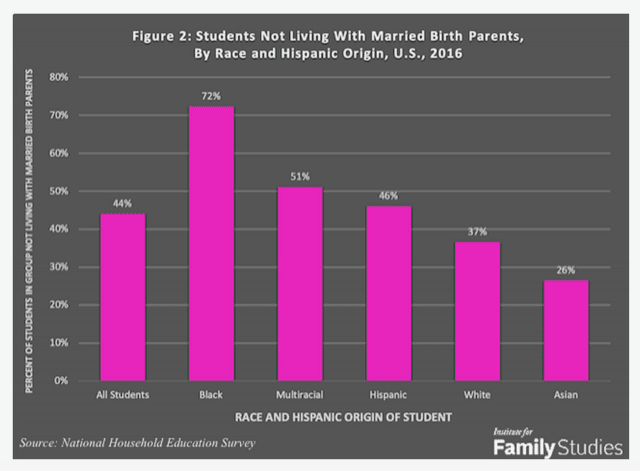

The researchers note the NHES shows “black students are far more likely to be living apart from their married birth parents in the home (72%) compared to white students (37%) or Asian students (26%).”

“These family structure differences, then, are likely to play a role in inter- and intra-racial disparities in student conduct and discipline,” the authors state, and add:

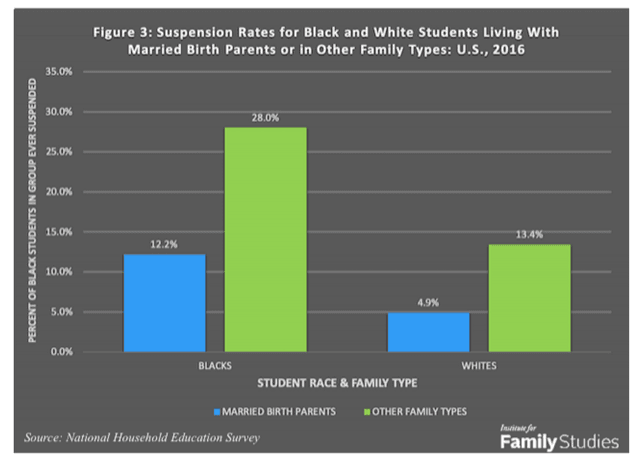

Indeed, among black students who do live with both married birth parents, suspension rates are less than half as large as those for black students living in other family types: 12% versus 28%. The suspension rate for black students living in intact families, 12%, is also less than the suspension rate for white students from non-intact families, 13%.

The study also found that family structure even accounts for more of the racial disparities in school suspensions than socioeconomic factors.

When the researchers controlled for family structure, they discovered the racial disparities in school suspensions reduced by 55 percent. Controlling for socioeconomic status reduced the racial differences by only 38 percent.

“These results, then, suggest that family structure is a signal factor in accounting for real differences in school conduct and school suspensions,” the authors state. “This is especially noteworthy because discussions related to racial disparities in school discipline often overlook the role of family structure and highlight socioeconomic explanations.”

Zill and Wilcox assert that, while examples of racism exist, “there are legitimate reasons for believing that some of the racial differences in school suspensions and discipline are based upon real, not just perceived, differences in students’ behavior”:

We focus here on the possibility that some of these differences are related to family factors, including notable differences in family structure by race. Students who come from chaotic homes, single-parent families, or non-intact families are less likely to get the consistent attention, affection, and discipline they need to flourish and develop self-control. Their families typically have less money, which affects the quality of their neighborhoods and their neighborhood peers, which is also an important influence on school conduct. And they are also more likely to be exposed to conflict, stress, frequent moves, and neglect—all risk factors for delinquent and disruptive behavior. Indeed, our data indicate that rates of school contact for student misbehavior are nearly twice as high among students living with separated or divorced parents as among those living with stably married parents. And they are higher still among students who live apart from both biological parents, being cared for instead by grandparents or foster parents.

The researchers say that, in order to see a drop in school suspensions among black children and adolescents, black family life must be stabilized and reinforced:

Such efforts should include criminal justice reform, ending marriage penalties in means-tested policies, subsidizing the wages of low-income workers, and launching local and national campaigns directed by black religious, civic, and cultural leaders to strengthen marriage in the black community. Efforts like these are needed because, our research suggests, increasing the number of African American children who are raised by stably married parents would dramatically increase the odds that black girls and boys steer clear of the principal’s office—and increase the odds they flourish in school, avoid contact with the criminal justice system, and, later in life, excel in the labor force further down the road.

“[S]tronger black families would go a long way towards reducing racial disparities in school discipline,” Zill and Wilcox assert.

The study comes as Obama-era holdovers and other progressives continue the narrative that racial disparities in school suspensions and discipline are due to systemic factors such as institutional racism.

The Obama Departments of Education and Justice, under Education Secretary Arne Duncan and Attorney General Eric Holder, issued public school guidelines that claimed students of color are “disproportionately impacted” by suspensions and expulsions, a situation they said led to a “school-to-prison pipeline” that discriminates against minority and low-income students.

The policy, however, essentially blamed systemic racism for the fact that black and other minority students have been punished and suspended more than white and Asian students. Recommended remedies for the problem included eliminating suspensions for unacceptable behavior by minority students and urging, instead, their participation in “restorative talking circles” and “positive behavior interventions.”

In December 2018, the Trump administration revoked the Obama-era policy that urged public schools to employ these more lenient forms of discipline for students of color and of other minority groups.

The U.S. Departments of Education and Justice rescinded the Obama administration’s 2014 “Dear Colleague Letter” that a federal school safety commission said “may have paradoxically contributed to making schools less safe.”

The outcry from parents, teachers, some media outlets, and many education analysts and stakeholders has been piercing, with most pointing to the rise in “dangerousness” in public schools.

Nevertheless, in July, Democrat members of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission urged the White House and Congress to continue the Obama-era race-based discipline policy.

The commission’s report, titled “Beyond Suspensions: Examining School Discipline Policies and Connections to the School-to-Prison Pipeline for Students of Color with Disabilities,” stated, “[D]ata have consistently shown that the overrepresentation of students of color in school discipline rates is not due to higher rates of misbehavior by these students, but instead is driven by structural and systemic factors.”

The commission’s report was released as the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) issued its analysis indicating a rise in serious incidents of violence in the nation’s public schools:

Even a Democrat state lawmaker — New York State Sen. Leroy Comrie — and Teamsters President Gregory Floyd, who represents school safety officers — referred to the Obama-era policy as one that has led to “chaos” and a lack of “accountability” for dangerous behavior.

Two members of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission — Peter Kirsanow and Gail Heriot — dissented from the commission’s majority report.

Kirsanow wrote at National Review the report is “essentially a defense of the Obama Department of Education’s 2014 ‘Dear Colleague’ letter that used disparate-impact theory to interpret racial disparities in school discipline as evidence of racial discrimination.”

To progressives, “any racial disparity necessarily means invidious racial discrimination,” Kirsanow asserted, adding:

It’s undisputed that black students, as a group, are disciplined more than white students. For the commission majority, this is evidence of racially disparate treatment, as it’s an article of faith that discipline disparities aren’t due to disparities in behavior.

Kirsanow observed the commission’s report ignored key statistics in order to craft its narrative of racial discrimination against students of color.

He pointed to his colleague Heriot’s statement in which she said, “In the report, the Commission finds ‘Students of color as a whole, as well as by individual racial group, do not commit more disciplinable offenses than their white peers.’”

“That would be a good thing if it were true, but there is no evidence to support it and abundant evidence to the contrary,” she asserted, adding that what accounts for differing rates of misbehavior among students of color “likely” includes “differing rates of poverty, differing rates of fatherless households, differing parental education, differing achievement in school, and histories of policy failures and injustices.”

Kirsanow called for those truly concerned about improving education in the United States to “disregard” the report released by the majority of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.

“Claiming that racism or dislike of children with disabilities accounts for disparate rates of discipline only stokes resentment and erodes personal responsibility,” he asserted. “The supposed cures of ‘restorative practices’ and ‘positive behavioral interventions and supports’ only make it more likely that children in minority neighborhoods who want to learn will be less able to do so, and that teachers and children will be at the mercy of school bullies.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.