There’s a reason why any proposed ambitious national undertaking is compared to the Apollo 11 moon mission. The Apollo landing, the 50th anniversary of which we celebrate on July 20, is the gold standard for collective achievement.

After all, less than seven decades after the American Wright Brothers proved that heavier-than-air aviation was even possible, other Americans had transcended the atmosphere altogether, traveling through outer space to the moon and back. Not bad!

That’s why today, the vision of curing cancer is referred to as a “moon shot,” as are ambitious goals in the various realms of science, environment, and even business. As Aristotle said, we most admire that which is hard to do, and so of course the moon shot is admired—and emulated.

Yet if the U.S. accomplishment in 1969 was a watershed moment in human history, it was also a testament to the ability of Americans to organize to accomplish a great goal. As authors Robert Stone and Alan Andres have noted in their new book, Chasing the Moon: The People, the Politics, and the Promise That Launched America into the Space Age:

The American effort to get to the moon was the largest peacetime government initiative in the nation’s history. At its peak in the mid-1960s, nearly two percent of the American workforce was engaged in the effort to some degree. It employed more than 400,000 individuals, most of them working for 20,000 different private companies and 200 universities.

The space program was not just about the guts and grit of astronauts with “the right stuff,” nor about the brilliance of the engineers who designed the spacecraft. It was also about the financial and organizational ability of government leaders, corporate executives, and white- and blue-collar workers—all teaming up to get the job done.

The roots of this powerful teamwork go back to World War II. The Can Do spirit that animated America in the 1940s enabled Uncle Sam to build his mighty Arsenal of Democracy, which included the construction of more than 300,000 airplanes. Among these aircraft were bombers capable of dropping 1.5 million tons of ordnance, to cite just one war-winning metric. And of course, two of those bombs were atomic bombs, further reminding us of just how much we can get done when we throw ourselves into an urgent mission.

As a shining example of World War II’s Arsenal of Democracy, Ford’s Willow Run plant workers put the finishing touches on the B-24 Liberator bombers coming off the assembly lines on March 3, 1943. (AP Photo)

In fact, as this author has argued here at Breitbart News, the U.S. scientific and industrial achievement in World War II, stupendous as it was, would not have been possible unless a giant industrial base had already been in place before the fighting started. In fact, the origins of our industrial muscle reach back to Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay, those far-seeing champions of tariffs and internal improvements—what became known as American System.

We can further add that nationwide economic development, as well as overall American strength and greatness, was the conscious goal of Hamilton and Clay; in the 20th century, leaders acting in their tradition sought to make sure that NASA spending was spread around, not just clustered in the richer Northeast. Thus it was that NASA rockets were built in Alabama, stocked with avionics from California, launched from Florida, and mission-controlled from Texas. This is how nations get built—they do things as a team.

Returning to the mid-20th century, we can note that the success of the homefront in providing superior weapons for the warfront demonstrated that a new kind of military system had emerged, based on Big Science. That is, government, industry, and the academy were all combining to crank out lethally effective inventions.

In that new spirit of marshaling the national mojo, on July 25, 1945, Vannevar Bush, head of R&D for the Pentagon during the war, submitted a report, Science the Endless Frontier, to President Harry Truman and to the nation. In that document, Bush outlined a postwar plan for harnessing scientific potential on behalf of national missions, including military strength, economic growth, and medical advances:

The pioneer spirit is still vigorous within this nation. Science offers a largely unexplored hinterland for the pioneer who has the tools for his task. The rewards of such exploration both for the Nation and the individual are great. Scientific progress is one essential key to our security as a nation, to our better health, to more jobs, to a higher standard of living, and to our cultural progress.

Bush’s report was well received, as most policymakers back then, as well as most Americans, could see the value of coordinated efforts to solve problems. In fact, breakthroughs could, and did, more than pay back their cost; the polio vaccine, for example, delivered immense humanitarian benefits, and yet in terms of public-health cost-savings, it also proved to be one of the best investments ever.

In that era, another national undertaking was imposed on us: the need to wage, and to win, the Cold War. Once again, Big Science put its shoulder to the wheel, and America innovated anew; rocketry, the transistor, and the Internet were just three of the new boons to our security—and to our economy.

Indeed, the Can Do ethos was still so strong that, in 1960, Time magazine named “American Scientists” as its “Men of the Year.”

So it was in this forward-looking political and technological context that President John F. Kennedy, himself a World War Two vet, made his bold declaration on the moon shot. As he told Congress on May 25, 1961:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.

President John F. Kennedy speaks before a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961, urging congressional approval of funding for the space program. (AP Photo)

As the Seabees in JFK’s beloved Navy said as their motto, “The difficult we do now, the impossible takes a little longer.” Thus the 35th president gave the nation eight-and-a-half years to complete the moon mission—and as we know, NASA beat the deadline by six months.

The following year, 1962, Kennedy elaborated on the national goal. We should go to the moon, he told an audience at Rice University, “because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.” That is, we would extend Big Science up, way up, and so “become the world’s leading space-faring nation.”

On May 5, 1961, at the White House, (from L-R) Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Arthur Schlesinger, Admiral Arleigh Burke, President John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy watch the flight of astronaut Alan Shepard on television. (AFP/Getty Images)

On Feb. 23, 1962, astronaut John Glenn and President John F. Kennedy inspect the Friendship 7, the Mercury capsule in which Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth. (AP Photo/Vincent P. Connolly)

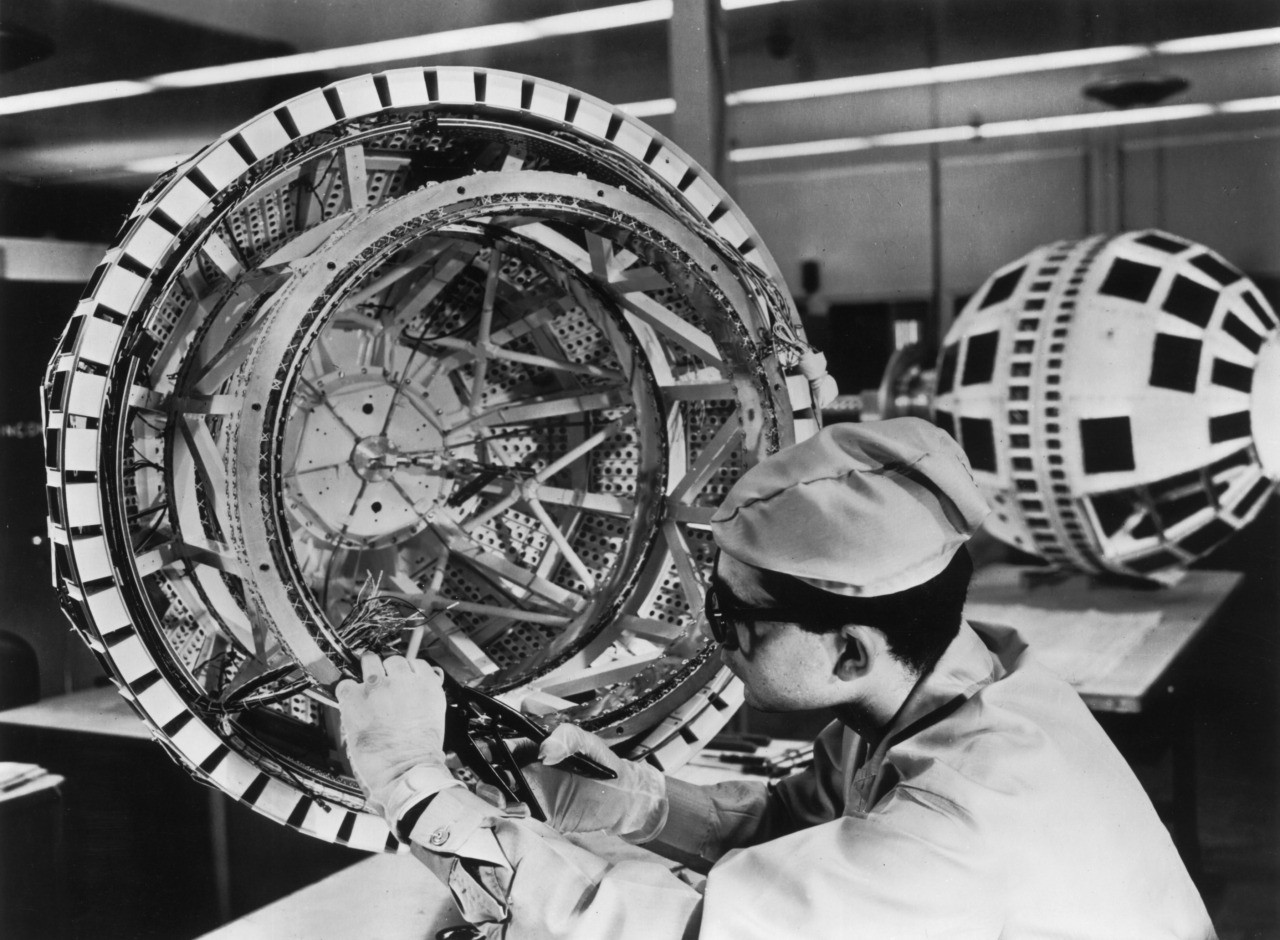

July 1962: A technician prepares to wire together the components of the Bell System’s Telstar experimental communications satellite, shortly before its launch into orbit. Telstar was the first satellite to relay television programs between Europe and the United States. (Keystone/Getty Images)

The popular culture was strongly supportive of the space program. The cartoon show The Jetsons premiered on primetime network television in the fall of 1962, and Star Trek, starring William Shatner as the Kennedyesque Captain Kirk, debuted in 1966. Every American in those days knew the show’s resonant opening cadence, “To boldly go where no man has gone before.”

In 1968, the Apollo 8 astronauts were named Time’s Men of the Year”—and they “merely” orbited the moon, taking, along the way, that iconic “Earthrise” photograph. In that same year, the Stanley Kubrick movie 2001 imagined routine commercial shuttle flights to the moon, as well as a manned mission to Jupiter.

The famous “Earthrise” photograph taken as Apollo 8, the first manned mission to the moon, entered lunar orbit on Christmas Eve, Dec. 24, 1968. That evening, the astronauts-Commander Frank Borman, Command Module Pilot Jim Lovell, and Lunar Module Pilot William Anders-held a live broadcast from lunar orbit, in which they showed pictures of the Earth and moon as seen from their spacecraft. Said Lovell, “The vast loneliness is awe-inspiring and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth.” They ended the broadcast with the crew taking turns reading from the book of Genesis. (NASA)

The crew of Apollo 8 in their space suits on a Kennedy Space Center simulator, Florida, USA, November 13, 1968. Left to right: James A. Lovell Jr., William A. Anders and Frank Borman. (Space Frontiers/Getty Images)

To be sure, plenty else was going on in the 1960s, much of it not conducive to national harmony in pursuit of vital goals. And yet the momentum of Big Science carried through, leading to the success of the moon landing at the end of the decade.

Computers at the Manned Spacecraft Center, later the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, in Houston, Texas, circa 1960. (Getty Images)

The prime crew of the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. Left to right: Neil A. Armstrong, commander; Michael Collins, command module pilot; and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot. (NASA/Newsmakers)

July 16, 1969: Neil Armstrong waving in front, heads for the van that will take the crew to the rocket for launch to the moon at Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida. (AP Photo)

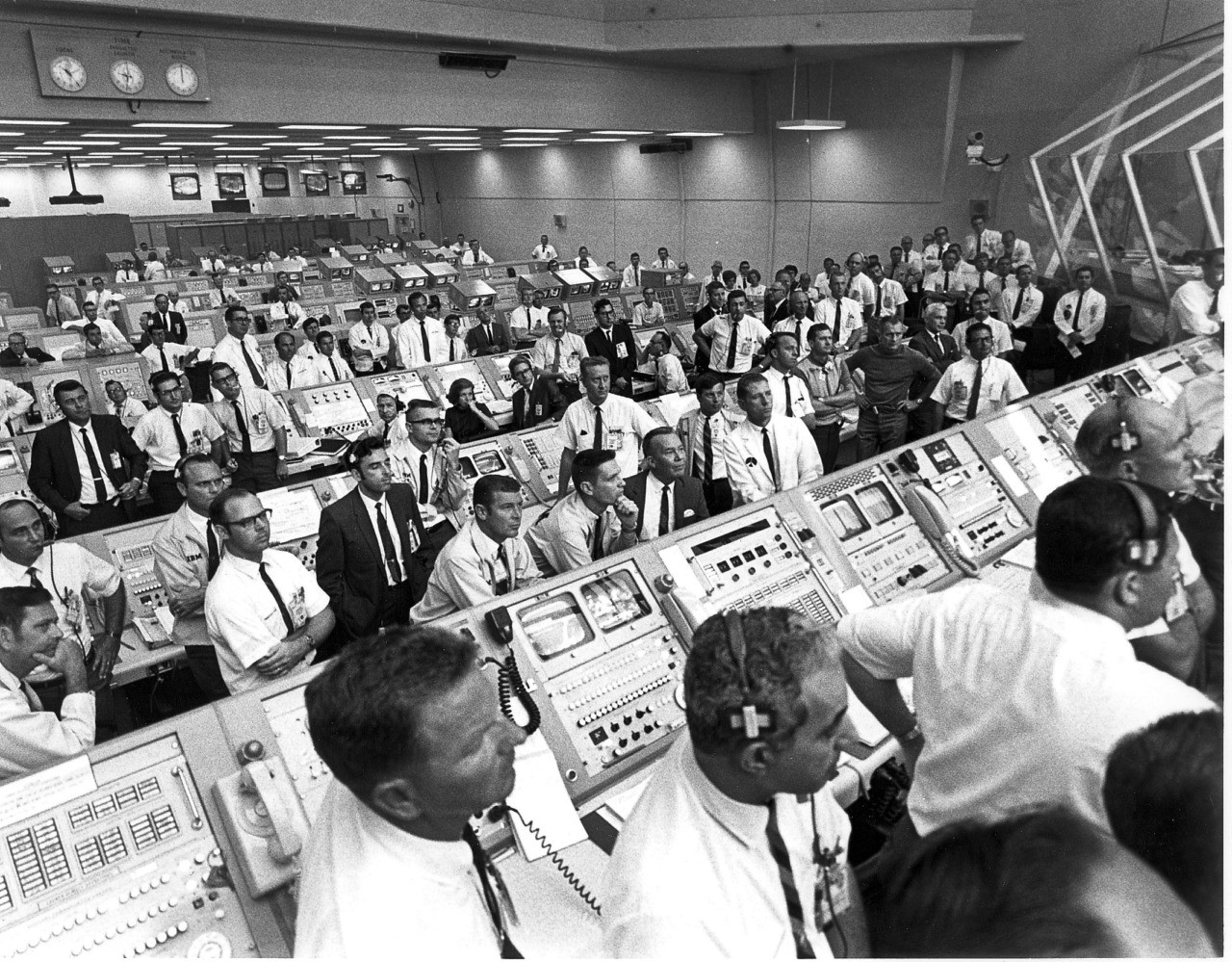

View of the Kennedy Space Center Control Room team, many standing behind their consoles, as they watch the liftoff of NASA’s Apollo 11 mission, Florida, July 16, 1969. Among those pictured is American aerospace engineer JoAnn H Morgan (seated center, with hand on chin) who, at the time, was NASA’s only female engineer. (NASA/AFP/Getty Images)

The Apollo 11 Saturn V space vehicle lifts off on July 16, 1969, from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex in Florida. The space craft was injected into lunar orbit on July 19 with Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. on board. (NASA/Newsmakers)

Parts of North America and Central America as seen from the Apollo 11 spacecraft during its translunar journey toward the Moon, on July 16, 1969. The spacecraft is 10,000 nautical miles from the Earth. (Space Frontiers/Getty Images)

The Apollo Lunar Module, known as the “Eagle,” descends onto the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969. (Space Frontiers/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

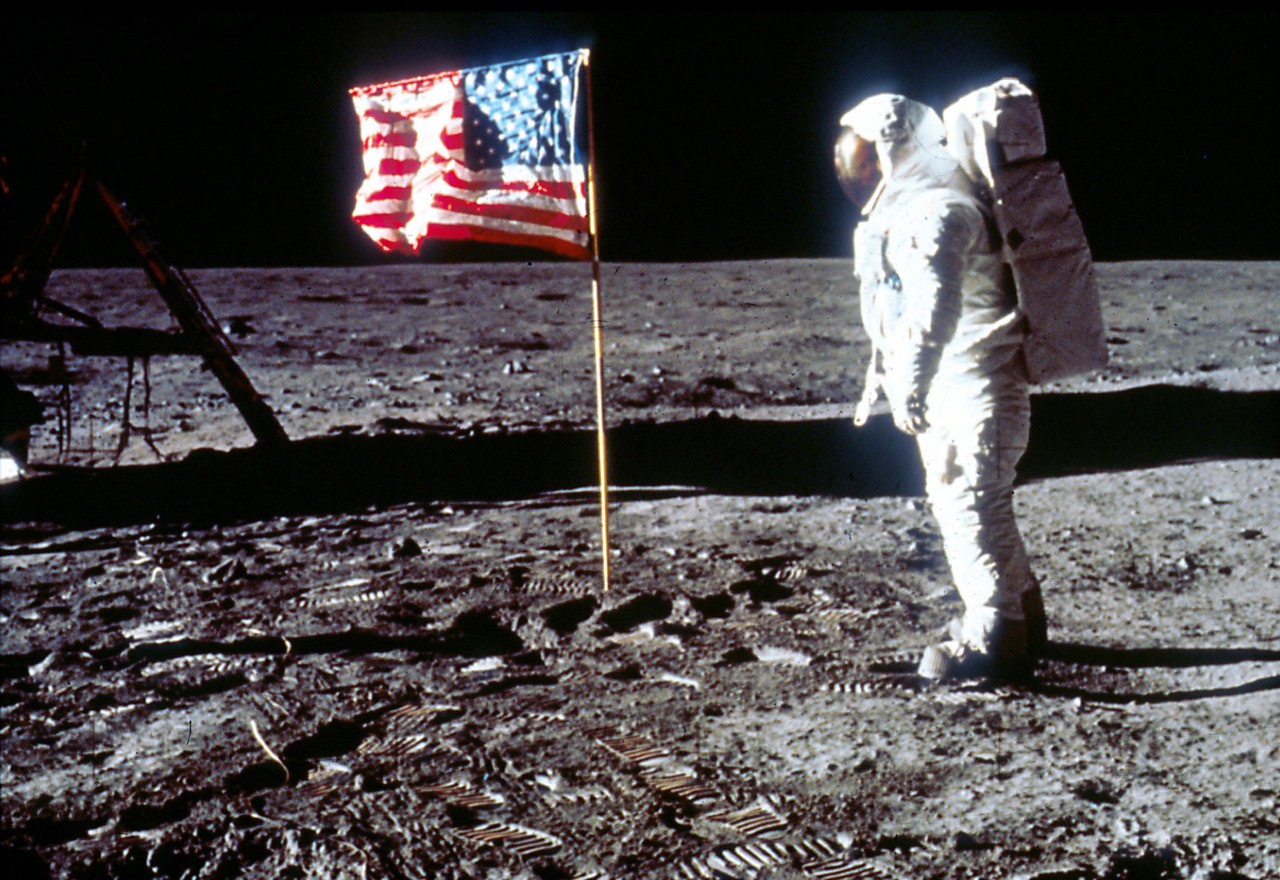

Neil Armstrong steps into history on July 20, 1969, by leaving the first human footprint on the surface of the moon. (NASA/Newsmakers)

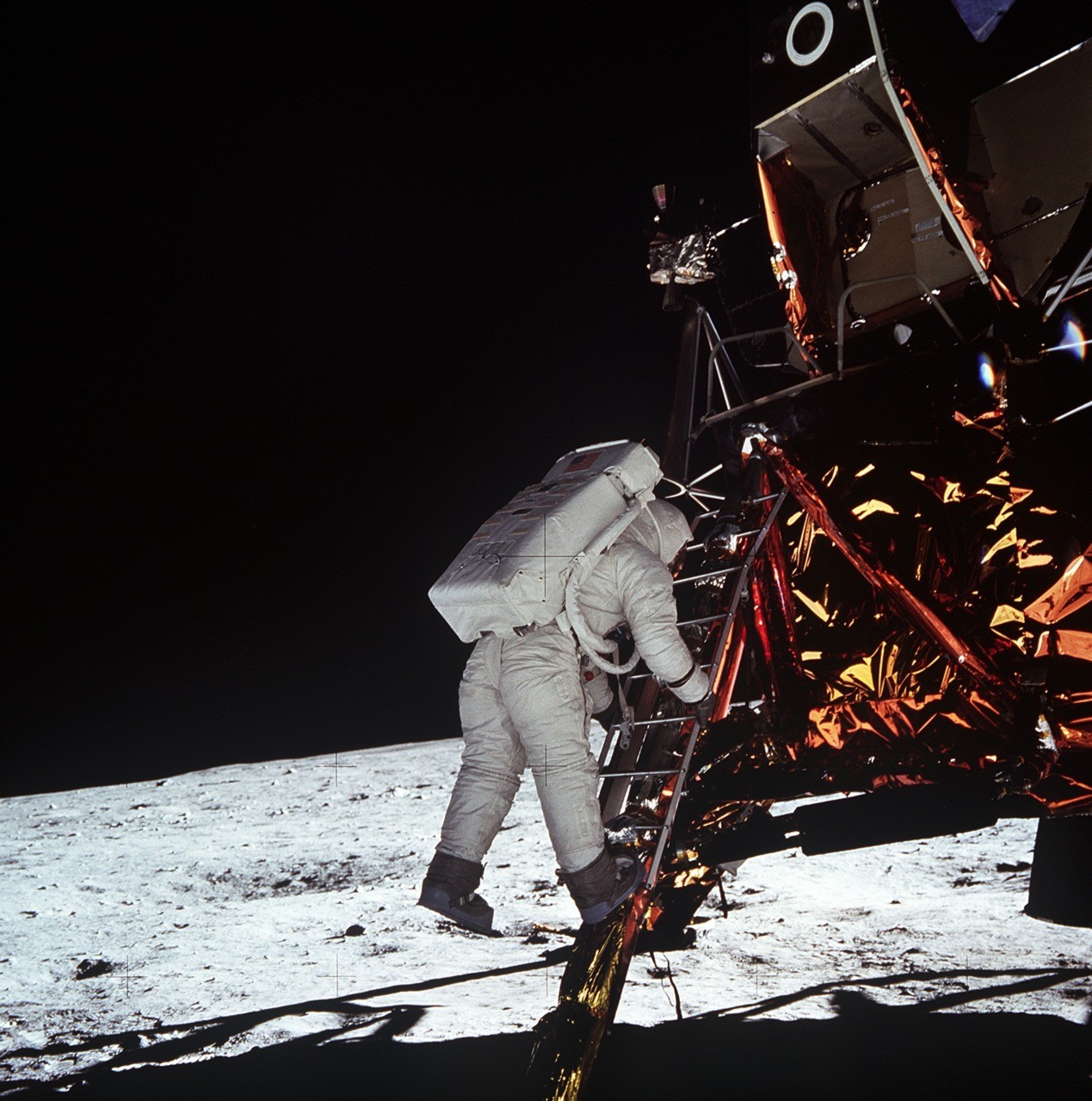

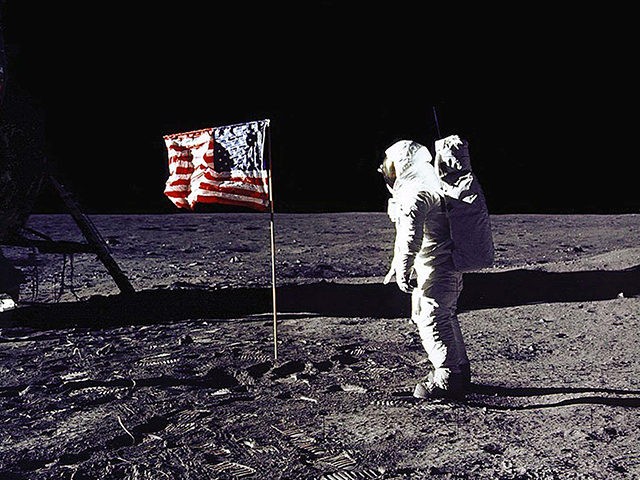

Astronaut Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr., lunar module pilot, descends the steps of the Lunar Module ladder on July 20, 1969, as he prepares to walk on the Moon. This photograph was taken by Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong with a 70mm lunar surface camera during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity. (NASA/Newsmakers)

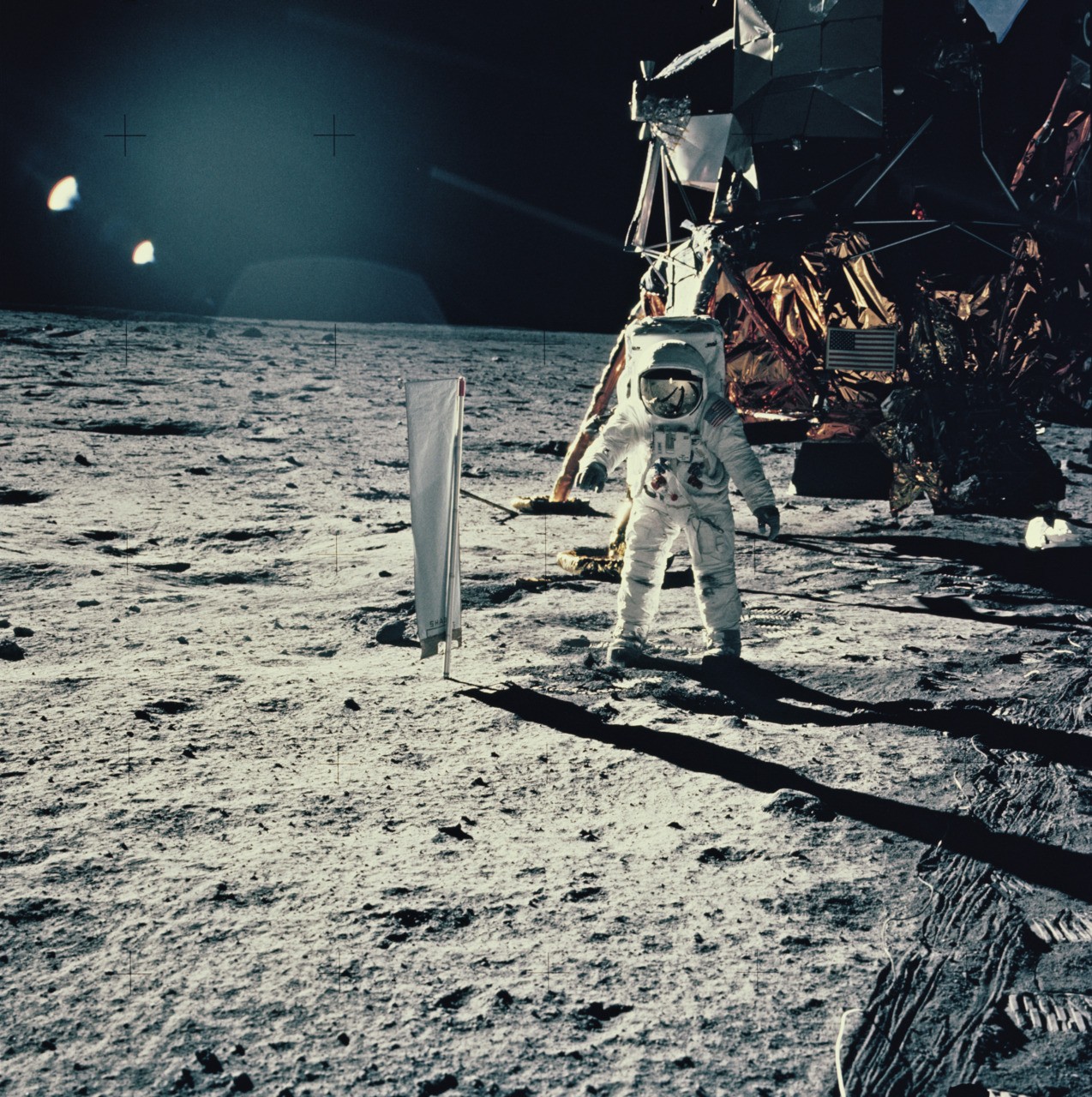

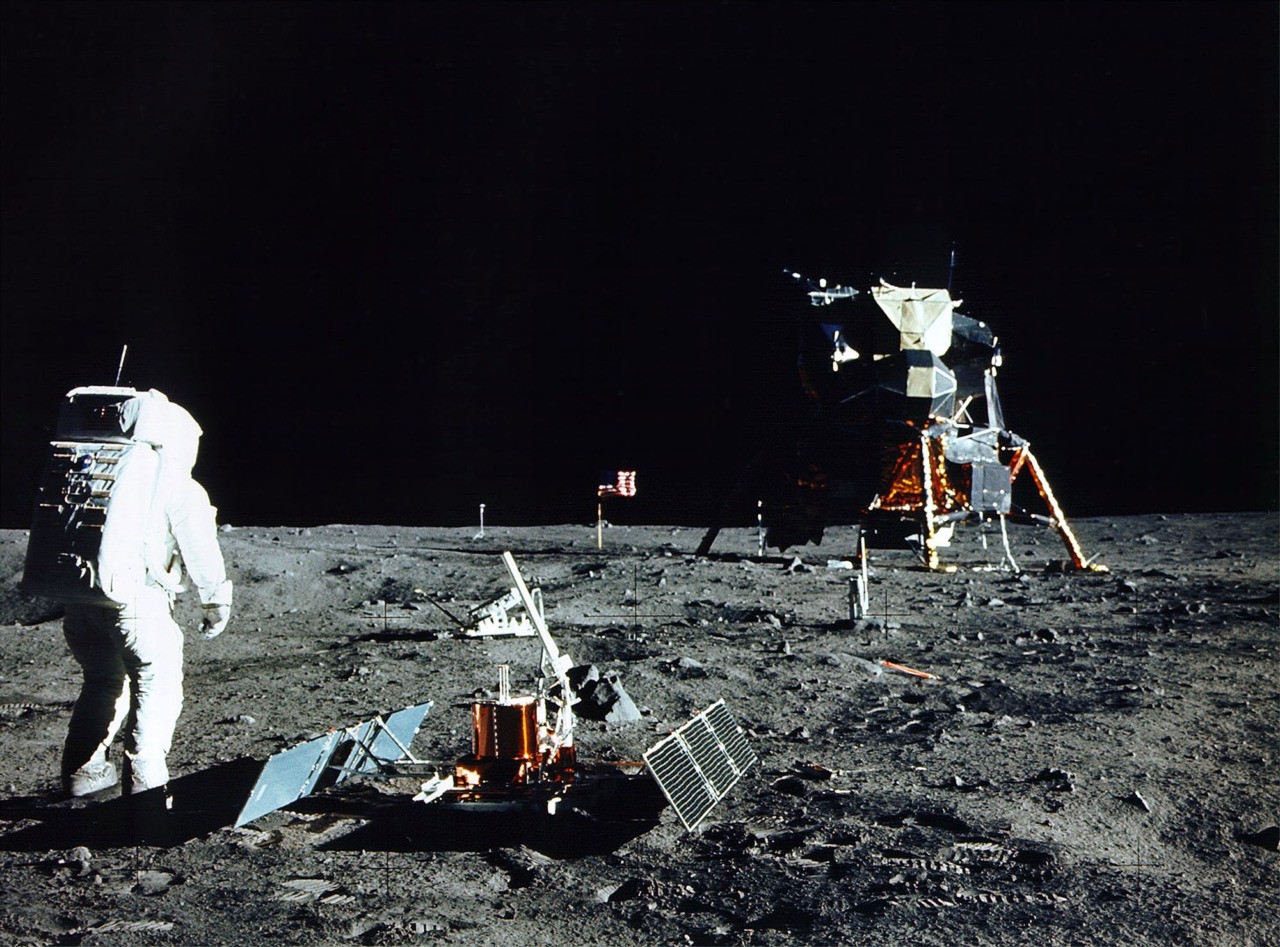

Buzz Aldrin standing next to the Solar Wind Composition experiment, part of the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASAP), at Tranquility Base on the surface of the Moon. The Apollo Lunar Module, the “Eagle,” is behind him. (Space Frontiers/Getty Images)

News anchor Walter Cronkite broadcasting the Apollo 11 moon landing on CBS-TV, July 20, 1969. (AP Photo)

An estimated 10,000 people gather around giant television screens in New York’s Central Park to watch and cheer as astronaut Neil Armstrong takes man’s first step on the moon on July 20, 1969. (AP Photo)

Italian and American residents watch the launch of the Apollo 11 Saturn V rocket on a TV set outside the United States Information Service (USIS) headquarters on the Via Veneto in Rome, Italy, July 16, 1969. (AP Photo/Claudio Luffoli)

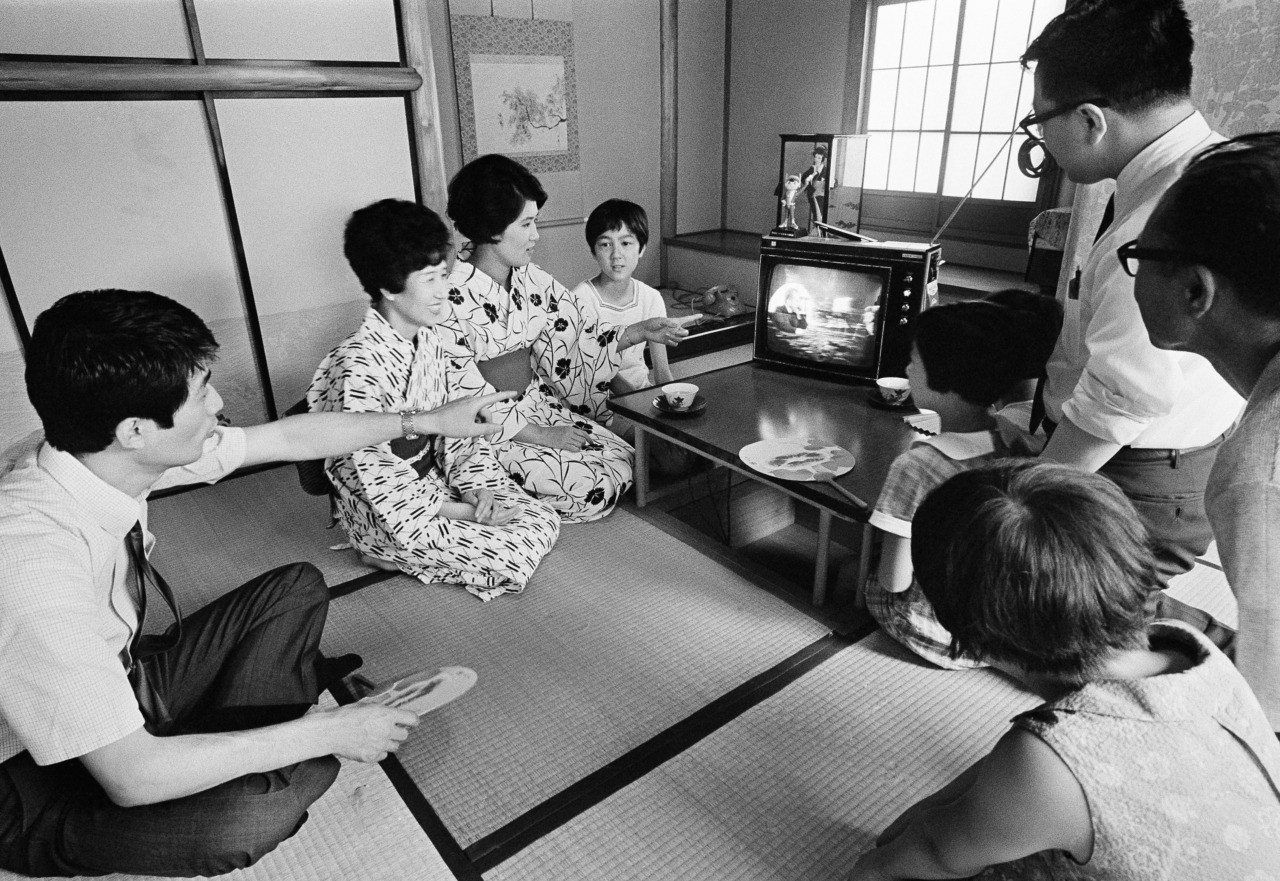

A Japanese family watch as U.S. President Richard Nixon is superimposed on a live TV broadcast of the Apollo 11 astronauts from the moon, July 21, 1969, Tokyo, Japan. (AP Photo)

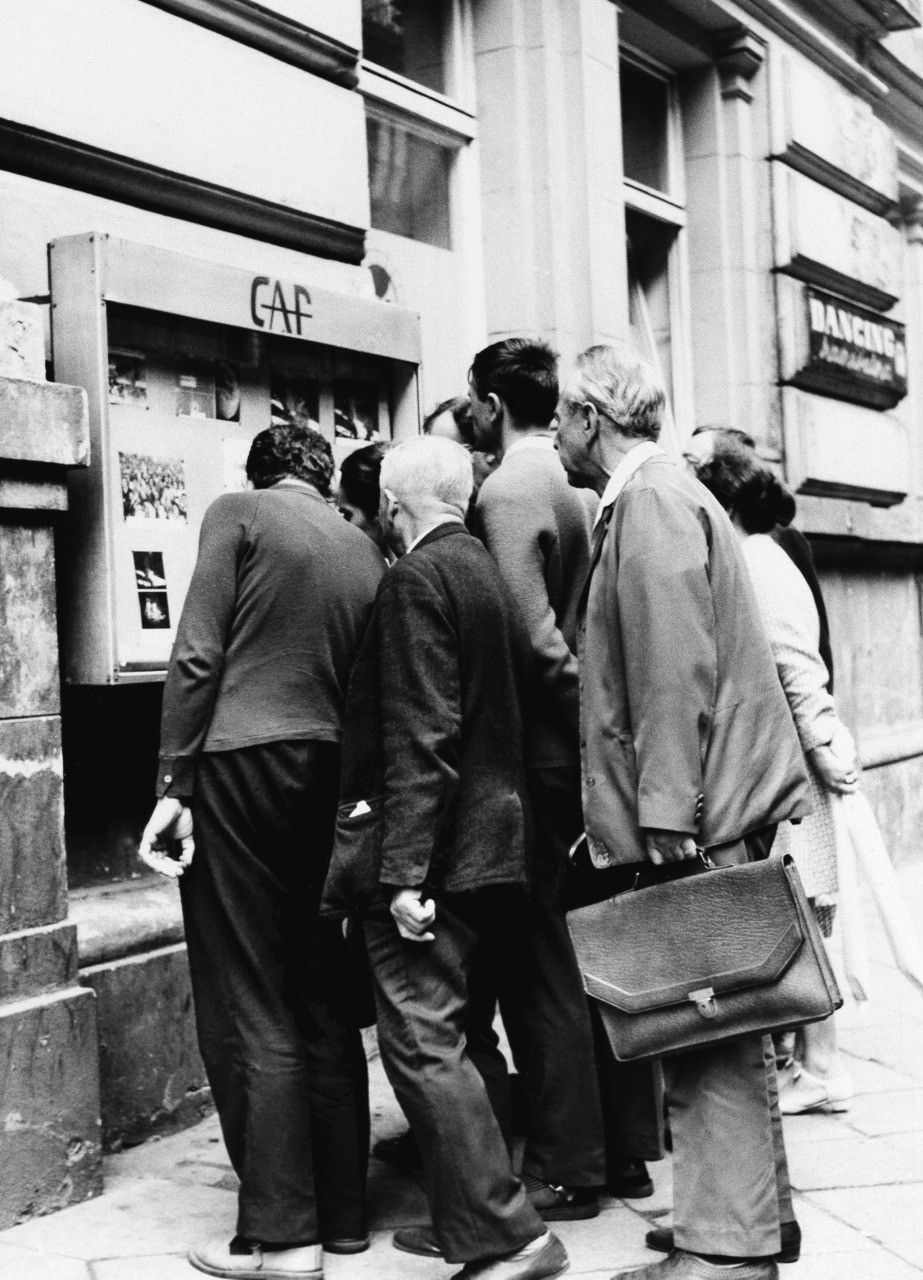

People gather in front of the Central Photo Agency office in Warsaw, Poland, to view photographs of the Apollo 11 moon landing, July 21, 1969. (AP Photo/Central Photo Agency)

Russians in the Soviet Union watch the Apollo 11 moon landing a few days after the live broadcast in July 1969. (AP Photo)

The Chicago Cubs (foreground), the Philadelphia Phillies, and fans in the stands in Philadelphia, July 20, 1969, bow their heads in a moment of silent prayer for the safe completion of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon. The players moved out on the field within the minute after the “Eagle” lunar module made its safe landing. The fans who had cheered wildly on hearing announcement of landing then joined the players in singing “God Bless America,” before resuming playing of second game of the day’s doubleheader. (AP Photo/Bill Ingraham)

New York City welcomes the Apollo 11 crew in a showering of ticker tape down Broadway and Park Avenue on August 13, 1969, in a parade termed as the largest in the city’s history. (NASA/Newsmakers)

Yet immediately after that small step, and that giant leap, the pro-space momentum faltered, ground down by a myriad of social factors, including the Vietnam War, race riots, and the druggy-hippie counter-culture.

Interestingly, the Apollo 11 crew itself seemed unaware of the sudden shift. Having been cooped up in Houston space simulators for years prior to their mission, the space heroes proved themselves naive about shifting sociocultural dynamics. Just days after returning to earth, Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, told Face the Nation, “I am quite certain that goals of the Mars variety are within our range”; he suggested a target year of 1981. Fellow astronaut Mike Collins added hopefully, “I don’t think 1981 is too soon.”

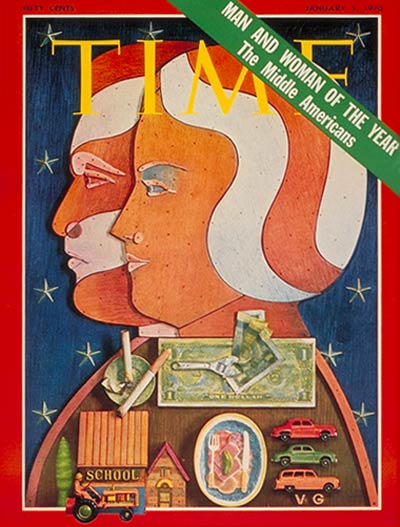

Sadly, that was not to be. Indeed, the implausibility of such an ambitious timeline could soon be seen on the cover of Time magazine. Whereas just a year before, the Apollo 8 crew had been named “Men of the Year,” in 1969 the Apollo 11 crew failed to win that annual accolade. Instead, the honor went to “The Middle Americans.” That’s right, the new national preoccupation was very down-to-earth.

Thus the ’60s ended on a far different note than they began. Ambitious declarations about promethean potential were out, while simpler considerations of domestic politics were in. Thus the space program sputtered; the last Apollo astronaut on the moon walked there in 1972. Meanwhile, the ’70s were absorbed by new concerns, from the environment to feminism, from the energy crisis to inflation.

Of course, the development of commercial space, mostly in the form of satellites, continued to go forward. In fact, the benefits of the now substantially privatized Big Science proved enormous, including the Global Positioning System, GPS. Indeed, all along over past decades, fatcats have kept up their interest in space.

Yet still, the sort of national dedication that characterized the space effort during the Mercury/Gemini/Apollo era had dissipated. Indeed, we might recall one particular low point during the long space recession: Back during the 2012 presidential campaign, Mitt Romney did his best to make sure space enthusiasm stayed dissipated when he heatedly, and short-sightedly, denounced GOP rival Newt Gingrich’s idea of lunar mining colonies.

Happily, today, after so many decades of drift, the American space program is making a comeback. The Trump-Pence administration has been a stalwart champion, pledging a return to the moon as well as a trip to Mars.

Moreover, the 50th anniversary celebrations of Apollo 11, on the National Mall and elsewhere, are a good indicator that nostalgia for those heady space days is growing stronger—and that’s sure to boost the space program in the future.

We can also add another reason for the resurgence: the specter of international competition. That is, if China and other countries are gearing up for space, well, that’s a spur to us—we shouldn’t let ourselves get left behind.

After all, the need to “compete” in World War II and in the Cold War greatly accelerated our patriotic determination to strive, to seek, and not to yield. So now today, the economic and strategic threat from China could have a similarly galvanic effect on American priorities.

Already, Sen. Ted Cruz has emerged as a champion of NASA, while Sen. Marco Rubio has focused on the economic threat from China. If those two leaders can work together, they can make a powerful argument for a boldly proactive space policy. After all, none of us should want to see China, to name one international rival, ever gaining undisputed control of the supranational high frontier of space or perhaps the moon.

Moreover, it’s not too late for us to recapture the roaming spirit of Star Trek’s Captain Kirk. Yes, we can still become the spacefaring civilization that John Kennedy envisioned, boldly going where no, er, person has gone before.

Indeed, JFK’s vision was so grand that we might some day look back at the moon shot and say, yes, that was the hinge of human history—when we got serious about spacefaring, and all of a sudden, earth looked too small to be home to all of our dreams.

Thus we might think back to Kennedy’s speech at Rice University in 1962, when he recalled the famous words of George Mallory who was asked why he wanted to climb to the summit of Mount Everest: “Because it is there.”

Then JFK added:

Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.

In the 20th century, JFK plotted the course, and a few years later, Apollo 11 fulfilled the mission.

Now, hopefully, in the 21st century, inspired once again by that epic success, America will get back to its manifest destiny: continuing on with, as JFK called it, the “greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.